This is the first part of my complete notes for Symmetric Cryptography, covering such topics as Keystreams, Modular Arithmetic, Integer Rings, Shift Ciphers, Affine Ciphers, Stream Ciphers, Linear Feedback Shift Registers, and more.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Symmetric Cryptography, Part 1: Intro & Stream Ciphers.

Table Of Contents

I. Introductions

I.I Classification & Terminology.

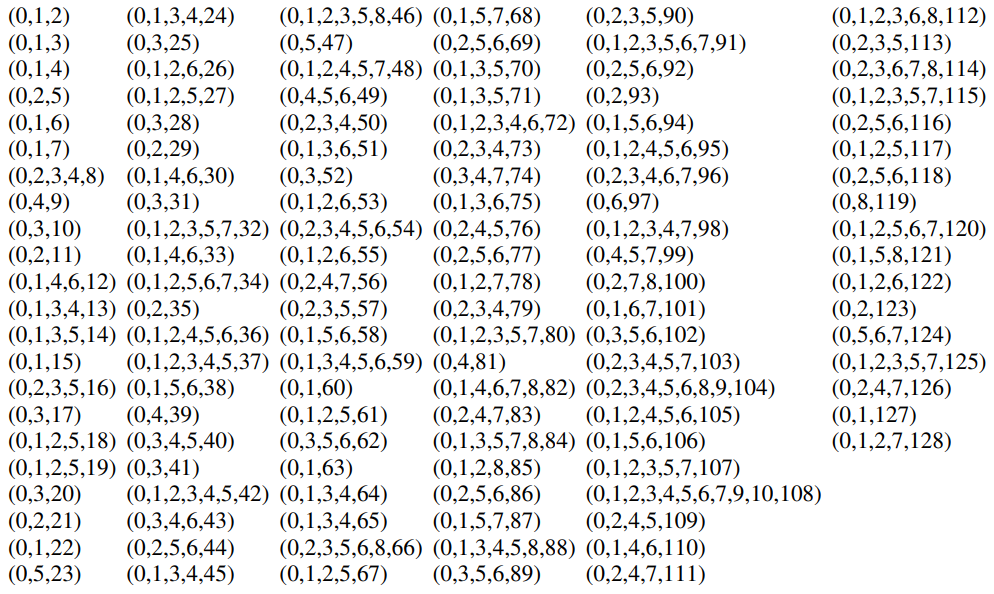

# Fig. 1. - Cybersecurity Classification Hierarchy:

A Classification Hierarchy of the major components of Cryptology. For a further classification of Cryptanalysis, see Rule 7, and III.I for Symmetric Cryptography. The work of the mastermind Jonathan Lacabe himself.

# Cryptology/Cybersecurity: IT Security - the protection of digital information against misuse, incorporating technical, organizational, and implementation-specific aspects. This is the modern, digital theater of the much greater field of 'Security'.

All IT Security follows the CIA Triad: Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability of information. Security is largely focused on protecting against attackers, while system safety & reliability is focused on protecting against random technical failures.

# Cryptography: A sub-field of Cryptology;

The science of securing communication through encryption, especially against the cryptanalysis efforts of an adversary. Cryptographic algorithms are the bedrock of all cybersecurity systems - if cybersecurity is a car, then Cryptography is the engine.

# Cryptanalysis: A sub-field of Cryptology;

The reductive counterpart to Cryptography, the science of 'breaking' encryption and bypassing the cryptographic security. Though it is the medium of hackers and cybercriminals, it is also a serious scientific field for researchers to test the security of cryptosystems, i.e. systems established using Cryptography (see definition). This is the only to absolutely ensure the security of the cryptosystem - remember Schneier's Law.

# Cryptosystem: An application/implementation of a set of cryptographic algorithms (incorporating encryption, decryption, and other mechanisms).

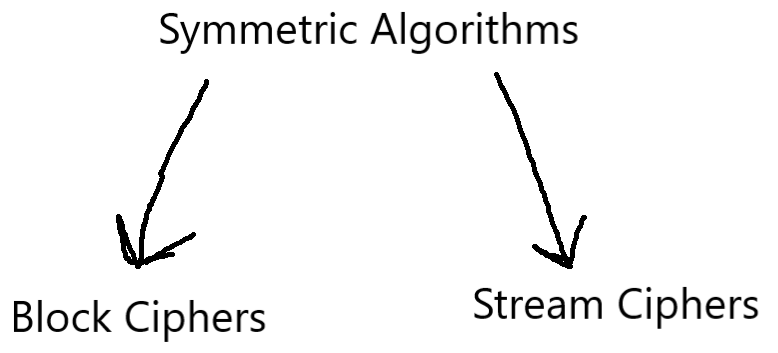

# Symmetric Algorithms: A sub-field of Cryptography;

The classic form of Cryptography - two parties hold a secret key, enabling one party to encrypt a message and the other party to decrypt it. Thus, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption.

Until 1976, this was the only form of Cryptography in existence, and describes the basic nature of all historical ciphers (such as the shift/caesar cipher and affine cipher) and Stream Ciphers, Block Ciphers, and DES & AES. Although it is indeed the classic form of Cryptography, it is still highly relevant today, as AES remains an industry standard even into the quantum age.

Hash functions are somewhat similar to symmetric algorithms, though they can be considered an independent, third type of Cryptographic algorithm.

# Asymmetric/Public-Key Algorithms: A sub-field of Cryptography;

The great cryptographic breakthrough of the 20th century, Asymmetric Cryptography (a.k.a. "Public Key Cryptography") is the backbone of most modern cryptosystems and is what much of the infrastructure of the Internet (protocols, in particular) is based on.

Invented by the Diffie-Hellman team in 1976, Public-Key Cryptography functions by having each party have TWO keys, a private key and a public key.

For more detail on how these algorithms work, see the "Public-Key Cryptography" Subcategory ([[[[[), but know they are used in a variety of fashions: digital signatures, key establishment/management, and more!

# Protocols: A sub-field of Cryptography;

Collective cryptographic algorithms that serve a complex security function, like a library of algorithms that work together for a common goal. For example - the Transport Layer Security scheme (TLS) and the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) are used in every web browser.

In the words of Edward Snowden, "[The Internet of Things and countless] protocols have given us the means to digitize and put online damn near everything in the world that we don’t eat, drink, wear, or dwell in."

#

C. Rule .

In Cryptography, 'Primitives', 'Ciphers', and 'Algorithms' all refer to different parts of the same process: the components of a cryptosystem at different scales, algorithms being the largest scale component and primitives being the smallest.

Primitives are the basic cryptographic functions (building blocks of an algorithm), Ciphers are the implementation of an encryption scheme, and Algorithms are the combined procedures of primitives and ciphers to create the greater cryptosystem.

For example, a well-formed algorithm may incorporate the AES cipher (see Rule [[[), which uses the key schedule primitive (see Rule 51) to assist in both encrypting and decrypting the data.

Primitives are the basic cryptographic functions (building blocks of an algorithm), Ciphers are the implementation of an encryption scheme, and Algorithms are the combined procedures of primitives and ciphers to create the greater cryptosystem.

For example, a well-formed algorithm may incorporate the AES cipher (see Rule [[[), which uses the key schedule primitive (see Rule 51) to assist in both encrypting and decrypting the data.

# Channel: A transmission medium for data to pass through. Examples include the Internet, airways, and Wi-Fi. Securing transmitted data from being intercepted, and from being intercepted in any meaningful form, is the goal of Cryptography.

# Hybrid Schemes: The combined usage of both asymmetric and symmetric algorithms in a cryptosystem, since both types have their own strengths and weaknesses (See [[[).

I.II Symmetric Crypto. Basics.

#

C. Rule .

Symmetric Cryptosystem:

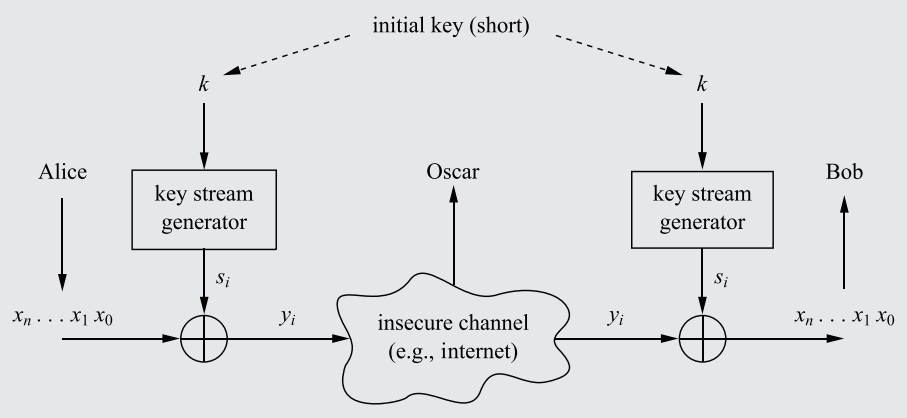

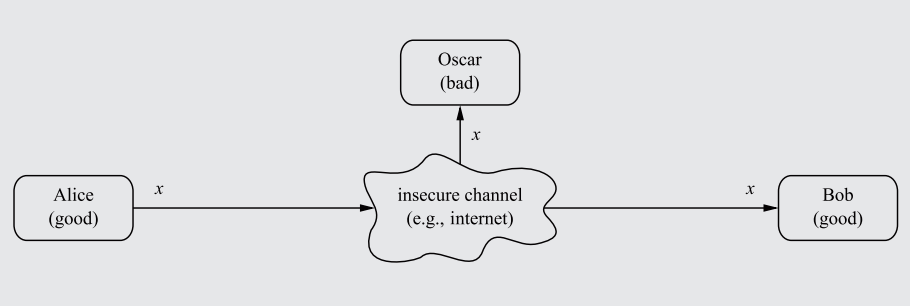

The ancient problem presents itself: How can two parties communicate over an insecure channel (an 'open channel') without having their communications intercepted by a third-party?

Say Alice and Bob connect through the internet (which is an open channel due to the potential of package rerouting/interception) and transfer data. An opponent, Oscar, can read their communications by intercepting the data before it reaches Bob.

A diagram showcasing how communications between Alice and Bob, when passing through an insecure channel unencrypted, can be intercepted by the attacker Oscar.

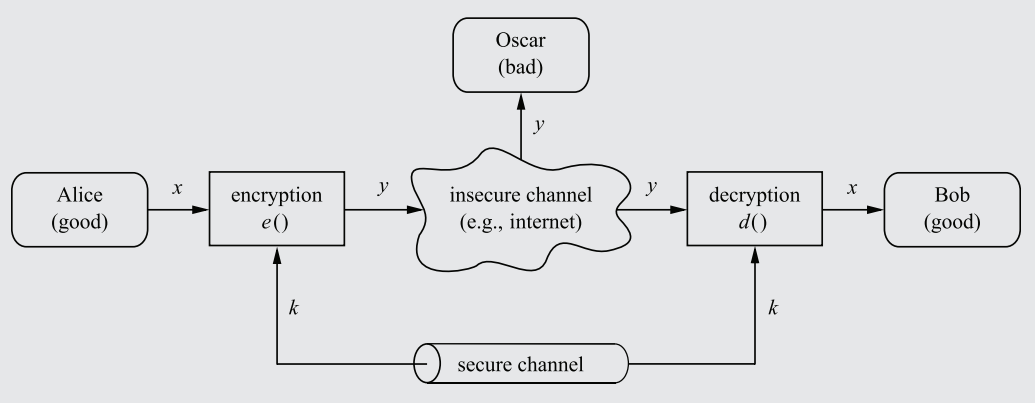

To stop Oscar from reading the message, an encryption algorithm can be established, converting the plaintext message (x) into a ciphertext message (y), and then sending it through the insecure channel. Oscar would only see a stream of random characters/bits as a result of the encryption. Bob, using a decryption function, would convert the ciphertext back into plaintext, thus completing the data transfer without interception.

In order for Bob to not simply decrypt the ciphertext immediately using the decryption function (which, counterintuitively, should actually be made publicly available - see Rule 3), a Key only known to Alice and Bob (sent through a secure, impenetrable channel) must be used as a parameter in both the encryption and decryption functions.

The key must be inputted into the encryption function to influence the manner in which the plaintext is encrypted into cyphertext. Thus, only with the key will Bob be able to decrypt the Ciphertext. Oscar, who doesn't know the key, will be unable to decrypt the message, even if the decryption algorithm is public.

A diagram showcasing a symmetric cryptosystem, complete with a key sent through a secure channel and encryption/decryption functions.

x = Plaintext message - the unadulterated, original content of the message.

y = Ciphertext, which looks like scrambled characters to an interceptor like Oscar.

e = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

d = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

K = The Key fed into the encryption and decryption functions.

|K|, 𝒦 = Keyspace, the total number of possible keys in a cryptosystem. This matters significantly with regard to brute-force Cryptanalysis (see Rule 8), and entails other characteristics detailed in Rule 6.

The ancient problem presents itself: How can two parties communicate over an insecure channel (an 'open channel') without having their communications intercepted by a third-party?

Say Alice and Bob connect through the internet (which is an open channel due to the potential of package rerouting/interception) and transfer data. An opponent, Oscar, can read their communications by intercepting the data before it reaches Bob.

A diagram showcasing how communications between Alice and Bob, when passing through an insecure channel unencrypted, can be intercepted by the attacker Oscar.

To stop Oscar from reading the message, an encryption algorithm can be established, converting the plaintext message (x) into a ciphertext message (y), and then sending it through the insecure channel. Oscar would only see a stream of random characters/bits as a result of the encryption. Bob, using a decryption function, would convert the ciphertext back into plaintext, thus completing the data transfer without interception.

In order for Bob to not simply decrypt the ciphertext immediately using the decryption function (which, counterintuitively, should actually be made publicly available - see Rule 3), a Key only known to Alice and Bob (sent through a secure, impenetrable channel) must be used as a parameter in both the encryption and decryption functions.

The key must be inputted into the encryption function to influence the manner in which the plaintext is encrypted into cyphertext. Thus, only with the key will Bob be able to decrypt the Ciphertext. Oscar, who doesn't know the key, will be unable to decrypt the message, even if the decryption algorithm is public.

A diagram showcasing a symmetric cryptosystem, complete with a key sent through a secure channel and encryption/decryption functions.

x = Plaintext message - the unadulterated, original content of the message.

y = Ciphertext, which looks like scrambled characters to an interceptor like Oscar.

e = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

d = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

K = The Key fed into the encryption and decryption functions.

|K|, 𝒦 = Keyspace, the total number of possible keys in a cryptosystem. This matters significantly with regard to brute-force Cryptanalysis (see Rule 8), and entails other characteristics detailed in Rule 6.

#

C. Rule .

Keeping the encryption/decryption algorithms 'e' and 'd' secret, preventing their cryptanalysis by the enemy (known as Security by Obscurity), was standard procedure for the ~4000 year history of Cryptography prior to the discovery of public-key Cryptography. However, the only way of ensuring the security of the algorithms is to make them public so that they can be analyzed by cryptanalysts.

This is the central principle of a foundational law in Cryptography, postulated in 1883 by Auguste Kerckhoffs:

Kerckhoffs' Principle:

"A cryptosystem should be secure even if the attacker (Oscar) knows all the details of the system, with the exception of the secret key."

In Practice: Never use an untested Crypto algorithm! Furthermore, never roll your own crypto!

This is the central principle of a foundational law in Cryptography, postulated in 1883 by Auguste Kerckhoffs:

Kerckhoffs' Principle:

"A cryptosystem should be secure even if the attacker (Oscar) knows all the details of the system, with the exception of the secret key."

In Practice: Never use an untested Crypto algorithm! Furthermore, never roll your own crypto!

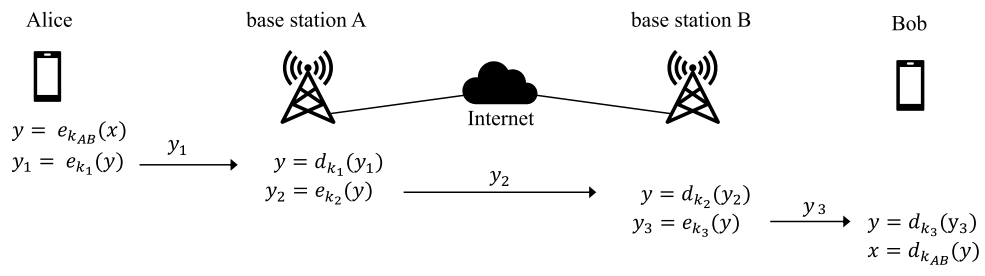

# End-To-End Encryption (E2EE): A system of encryption widely used in modern communication services (like internet messaging sites), in which all data sent from Alice to Bob (party #1 to party #2) is never decrypted at any point along its route until it reaches Bob.

Thus, all parties intercepting/eavesdropping will be unable to read or manipulate the message, even if they control any of the base stations the message goes through.

An example of how communications between Alice and Bob would occur under a end-to-end encryption scheme.

I.III Key Terminology.

Binary is a crucial element of how most (and practically all modern) cryptosystems work, and several phrases commonly used in cryptographic discussions directly reference this inherent nature. As such, let it be known: all references to 'bits' of any kind are made in regard to 1s and 0s.

#

C. Rule .

Bit-Length:

Mathematical Definition:

Value-based Bit-length = ⌊log2 N⌋ + 1

Set-based Bit-length = ⌈log2 S⌉

N = Any given number.

S = Any given set.

⌊, ⌋ = The Floor function, which returns the greatest integer less than or equal to the given value.

⌈, ⌉ = The Ceiling function, which returns the smallest integer larger than or equal to the given value.

Explanation:

Bit-length is a mathematical term with two definitions and two associated equations, the application of which depends on the context of what you are trying to find the bit-length of. Apart from being able to determine when to apply either definition, bit-length is a remarkably simple concept that hinges on comprehension of binary.

The first definition is value-based, while the second is set-based.

The bit-length of a value is the # of bits required to represent a given number.

The bit-length of a set is the # of bits necessary to represent the number of values within the set.

While the value-based definition is most popular in computer science (such as in the bit_length() method in Python), the set-based definition is the most popular and relevant in Cryptography. Thus, in cryptographic discussions, it is practically always safe to assume that the term 'bit-length' is being used in regard to the set-based definition.

As such, two distinct equations emerge to represent these binary operations. As shown in the mathematical definition, the value-based bit-length uses the floor function while the set-based bit-length uses the ceiling function, rounding downward and upward for any decimal value, respectively.

For an example of the two in practice, a keyspace of 2^3 (8 values) would have a value-based bit-length of 4, since 8 is 1000 in binary, and would have a set-based bit-length of 3, since exactly 3 bits would be required to account for every value within the keyspace: 000 through 111 represent a total of 8 values, reaching a highest value of 𝒦-1.

With regards to set-based bit-length, this does not mean that each individual value requires three bits to represent it; the value of 1 only "requires" 1 bit to represent it, for example. The set-based bit-length only really means the total number of bits necessary to represent 𝒦-1, which thus accounts for all of the values before it (through the nature of binary representation).

Mathematical Definition:

Value-based Bit-length = ⌊log2 N⌋ + 1

Set-based Bit-length = ⌈log2 S⌉

N = Any given number.

S = Any given set.

⌊, ⌋ = The Floor function, which returns the greatest integer less than or equal to the given value.

⌈, ⌉ = The Ceiling function, which returns the smallest integer larger than or equal to the given value.

Explanation:

Bit-length is a mathematical term with two definitions and two associated equations, the application of which depends on the context of what you are trying to find the bit-length of. Apart from being able to determine when to apply either definition, bit-length is a remarkably simple concept that hinges on comprehension of binary.

The first definition is value-based, while the second is set-based.

The bit-length of a value is the # of bits required to represent a given number.

The bit-length of a set is the # of bits necessary to represent the number of values within the set.

While the value-based definition is most popular in computer science (such as in the bit_length() method in Python), the set-based definition is the most popular and relevant in Cryptography. Thus, in cryptographic discussions, it is practically always safe to assume that the term 'bit-length' is being used in regard to the set-based definition.

As such, two distinct equations emerge to represent these binary operations. As shown in the mathematical definition, the value-based bit-length uses the floor function while the set-based bit-length uses the ceiling function, rounding downward and upward for any decimal value, respectively.

For an example of the two in practice, a keyspace of 2^3 (8 values) would have a value-based bit-length of 4, since 8 is 1000 in binary, and would have a set-based bit-length of 3, since exactly 3 bits would be required to account for every value within the keyspace: 000 through 111 represent a total of 8 values, reaching a highest value of 𝒦-1.

With regards to set-based bit-length, this does not mean that each individual value requires three bits to represent it; the value of 1 only "requires" 1 bit to represent it, for example. The set-based bit-length only really means the total number of bits necessary to represent 𝒦-1, which thus accounts for all of the values before it (through the nature of binary representation).

#

C. Rule .

Key-Length:

Mathematical Definition:

Key-length = ⌈log2 𝒦⌉

𝒦 = Keyspace, the total number of possible keys in a cryptosystem.

⌈, ⌉ = The Ceiling function, which returns the smallest integer larger than or equal to the given value.

Explanation:

Key-Length is a concept that builds upon the idea of bit-length, which is explained in Rule 4. Comprehension of bit-length (and the different between value-based and set-based bit-length) is prerequisite for understanding key-length.

In its essence, Key-length is a narrowed application of set-based bit-length specific to the bit-length of the key of a cryptosystem. It is identical in every way to the set-based bit-length definition, except for the minute change of "set" to "keyspace":

The bit-length of a keyspace is the # of bits necessary to represent the number of values within the keyspace. This value is known as the key-length.

Set-based bit-length, and its particular use-case of key-length, will appear with some ubiquity in the Cryptographic Summary. Note how key-length is basically just a subtype of bit-length, just like how keybits (see definition) are a more specific type of bit. However, they can NOT be used interchangeably, for reasons outlined below.

In Cryptography, the key-length is only relevant/existent if the cryptosystem uses binary representation, as detailed in Rule 6. The number of bits necessary to represent each value of the keyspace is meaningless if there are no 'bits' involved in the cryptosystem, as is the case for the Shift Cipher (Rule 20), which has a keyspace of 26 but no meaningful key-length. Somewhat ironically, bit-length does not require a bit-based system to have a meaningful result, as it merely denotes the process of converting a value to its binary form.

Mathematical Definition:

Key-length = ⌈log2 𝒦⌉

𝒦 = Keyspace, the total number of possible keys in a cryptosystem.

⌈, ⌉ = The Ceiling function, which returns the smallest integer larger than or equal to the given value.

Explanation:

Key-Length is a concept that builds upon the idea of bit-length, which is explained in Rule 4. Comprehension of bit-length (and the different between value-based and set-based bit-length) is prerequisite for understanding key-length.

In its essence, Key-length is a narrowed application of set-based bit-length specific to the bit-length of the key of a cryptosystem. It is identical in every way to the set-based bit-length definition, except for the minute change of "set" to "keyspace":

The bit-length of a keyspace is the # of bits necessary to represent the number of values within the keyspace. This value is known as the key-length.

Set-based bit-length, and its particular use-case of key-length, will appear with some ubiquity in the Cryptographic Summary. Note how key-length is basically just a subtype of bit-length, just like how keybits (see definition) are a more specific type of bit. However, they can NOT be used interchangeably, for reasons outlined below.

In Cryptography, the key-length is only relevant/existent if the cryptosystem uses binary representation, as detailed in Rule 6. The number of bits necessary to represent each value of the keyspace is meaningless if there are no 'bits' involved in the cryptosystem, as is the case for the Shift Cipher (Rule 20), which has a keyspace of 26 but no meaningful key-length. Somewhat ironically, bit-length does not require a bit-based system to have a meaningful result, as it merely denotes the process of converting a value to its binary form.

# Keybits: The binary bits in the key used in a cryptosystem. A key-length, for example, is composed of keybits. In Cryptography, a "256-keybit key-length" is regarded as secure against brute-force attacks (see Rule 8).

# Bits of Entropy/Key Entropy: A term frequently used in cryptography, essentially just meaning a number that represents the degree of security a cryptosystem has with respect to its keyspace. It has the equation ⌈log2 𝒦⌉, where 𝒦 is the keyspace of a cryptosystem (the number of possible keys). For example, if a cryptosystem has 2^100 keys, then that cryptosystem has 100 bits of entropy.

It really is just a term used to flex security against brute-force attacks (Rule 8), not in reference to anything tangible other than the size of the keyspace itself - it is a self-referential term, actively disguising useful information behind additional artificial buzzwords.

It happens to share the same equation as the key-length (as detailed in Rule 6 below), but note that "bits of entropy" is not a term chained to any particular requirement and can thus be applied to any cryptosystem, while the concept of a key-length has several prerequisites that limit its usage. This is in spite of the fact that "bits of entropy" uses the word "bit" - it, like bit-length (but unlike key-length, as distinguished in Rule 5), can be reasonably applied in non-bit-based cryptosystems.

#

C. Rule .

Keyspace Mathematics:

In Symmetric Cryptography, there is an inherent relation between the keyspace of a cryptosystem (|K| or 𝒦), and the key-length of the key (L) that the cryptosystem uses (which is dealt with in detail in Rule 5). It is fairly simple and intuitive, but has some key caveats.

If the algorithm uses a 168-bit key, then there are 2^168 possible keys. This is because the keyspace is the number of possible values that could be represented by the bits of the key-length - a key-length of 5 would have 32 possible values, i.e. every value between 00000 and 11111. Mathematically, this is represented using either of the following equations:

𝒦 = 2ᴸ

L = ⌈log2 𝒦⌉

These two equations are equivalent, with the second one derived by taking the log of both sides of the first (uncoincidentally forming the key-length equation as described in Rule 5). The ceiling function (which rounds to the closest greater number) is applied to the logarithm to ensure that the key-length is an integer. Of course, the relation only holds insofar that all keys of length L are valid and equally likely to occur, which rules out any symmetric cryptosystem with selective application of its keys/keybits.

There are some limitations that narrow the applicability of this relation - in effect, it only really applies to modern symmetric cryptosystems (unless specified otherwise, like the aforementioned DES). First, all ciphers that do not explicitly have a key-length, such as those that operate on letters instead of bits (e.g., every historical cipher in Section II), do not qualify. A cipher must structure its keys in the form of binary strings with fixed lengths in order for the relation to be applicable.

As stated in its definition, the very concept of a "keybit" is dependent on the fact that the cipher is using a key made from binary bits - any ciphers that do not meet that requirement are instantly null in regards to the given relation.

For example, the Shift Cipher (see Rule 20) has a keyspace of 26, but that in no way means that the "key-length" of the cipher is log2 26 (though it will indeed have log2 26 "bits of entropy"). For non-bit cryptosystems, there is no real key-length, but these ciphers are outdated nonsense cryptography that are not to be taken seriously anyways.

Furthermore, this relation does not hold for asymmetric cryptography: There is a significant difference between symmetric keys and asymmetric keys: a 128-bit symmetric key provides roughly the same security as a 3072-bit RSA (asymmetric algorithm) key. For information as to why this is, see Rule [[[.

In Symmetric Cryptography, there is an inherent relation between the keyspace of a cryptosystem (|K| or 𝒦), and the key-length of the key (L) that the cryptosystem uses (which is dealt with in detail in Rule 5). It is fairly simple and intuitive, but has some key caveats.

If the algorithm uses a 168-bit key, then there are 2^168 possible keys. This is because the keyspace is the number of possible values that could be represented by the bits of the key-length - a key-length of 5 would have 32 possible values, i.e. every value between 00000 and 11111. Mathematically, this is represented using either of the following equations:

𝒦 = 2ᴸ

L = ⌈log2 𝒦⌉

These two equations are equivalent, with the second one derived by taking the log of both sides of the first (uncoincidentally forming the key-length equation as described in Rule 5). The ceiling function (which rounds to the closest greater number) is applied to the logarithm to ensure that the key-length is an integer. Of course, the relation only holds insofar that all keys of length L are valid and equally likely to occur, which rules out any symmetric cryptosystem with selective application of its keys/keybits.

There are some limitations that narrow the applicability of this relation - in effect, it only really applies to modern symmetric cryptosystems (unless specified otherwise, like the aforementioned DES). First, all ciphers that do not explicitly have a key-length, such as those that operate on letters instead of bits (e.g., every historical cipher in Section II), do not qualify. A cipher must structure its keys in the form of binary strings with fixed lengths in order for the relation to be applicable.

As stated in its definition, the very concept of a "keybit" is dependent on the fact that the cipher is using a key made from binary bits - any ciphers that do not meet that requirement are instantly null in regards to the given relation.

For example, the Shift Cipher (see Rule 20) has a keyspace of 26, but that in no way means that the "key-length" of the cipher is log2 26 (though it will indeed have log2 26 "bits of entropy"). For non-bit cryptosystems, there is no real key-length, but these ciphers are outdated nonsense cryptography that are not to be taken seriously anyways.

Furthermore, this relation does not hold for asymmetric cryptography: There is a significant difference between symmetric keys and asymmetric keys: a 128-bit symmetric key provides roughly the same security as a 3072-bit RSA (asymmetric algorithm) key. For information as to why this is, see Rule [[[.

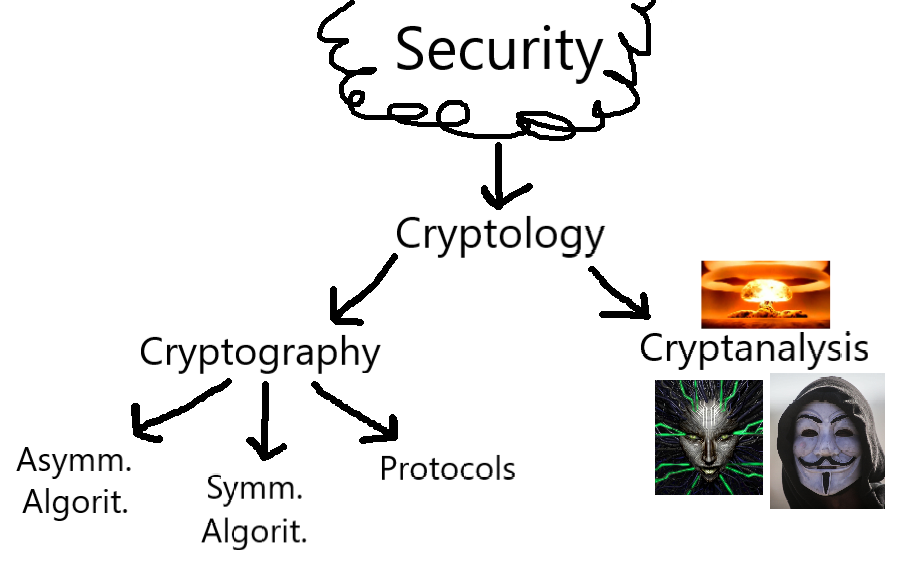

I.IV Cryptanalysis Basics.

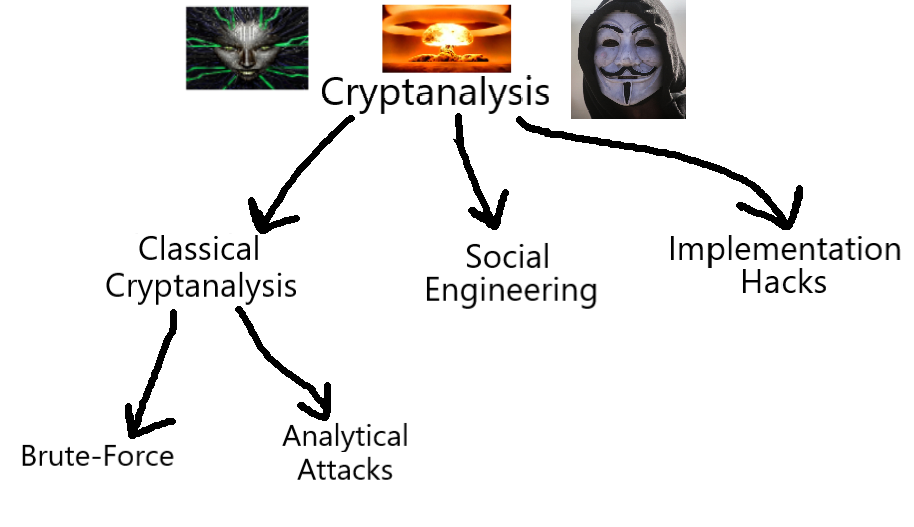

A Classification hierarchy of Cryptanalysis. There are two main branches of Classical Cryptanalysis, Brute-force and Analytical Cryptanalysis. See Subsection I.I for the full classification and III.I for Symmetric Cryptography.

#

C. Rule .

There are multitudes of cryptanalysis techniques, and the crucial law is that if just one attack works, then the entire cryptosystem crumbles and fails, regardless of how secure it is against other attack types.

For example, while a substitution cipher (see Rule 10) may be impenetrable to a brute-force attack (Rule 8) with its 2^88 keyspace, it collapses against letter frequency analysis (also described in Rule 10).

In order for a cryptosystem to be considered secure, it must be resistant against every single type of attack. An attacker always looks for the weakest link in the cryptosystem. Thus, in addition to strong algorithms, safeguards against social engineering and implementation attacks (see definitions below) must be instituted.

For example, while a substitution cipher (see Rule 10) may be impenetrable to a brute-force attack (Rule 8) with its 2^88 keyspace, it collapses against letter frequency analysis (also described in Rule 10).

In order for a cryptosystem to be considered secure, it must be resistant against every single type of attack. An attacker always looks for the weakest link in the cryptosystem. Thus, in addition to strong algorithms, safeguards against social engineering and implementation attacks (see definitions below) must be instituted.

# Classical Cryptanalysis: A sub-field of Cryptanalysis (see Fig. 2);

The basic, algorithm-focused approach to cryptanalysis in which you analyze the inputs and outputs to probe a viable attack vector. This is the "real" cryptanalysis in the eyes of the cryptography snobs, in which you try to poke holes in the design of the cryptosystem itself.

# Social Engineering: A sub-field of Cryptanalysis (see Fig. 2);

The process of bypassing the protections of a cryptosystem by going directly after the humans that have access to the secret key. Obtaining the key can range from kidnapping and forcing them to tell the key/password, to a simple phishing scheme over the phone or through email.

# Implementation Attacks: A sub-field of Cryptanalysis (see Fig. 2);

Extraction of the key through 'side-channel analysis'. By observing the behavior of the implementation of the cryptosystem in an IC or software, it is possible to deduce important information relating to the key.

For example: By looking at the electrical power consumption or electromagnetic radiation of a CPU running a cryptographic algorithm, a signal processing technique can be used to recover the key (see E.E. [[[[[). The runtime behavior can also indicate information regarding the key, which is why many cryptographers ensure constant runtimes in embedded cryptosystems.

These attacks are most relevant when the attacker has physical access to a piece of hardware running the cryptosystem, such as a credit card.

# Attack Vectors: The many possible ways to attack a cryptosystem; the types of cryptanalysis that can be used, including (but not limited to) those shown in Fig. 2.

# Moore’s Law: The computing power of the strongest computers (e.g., the number of transistors in an integrated circuit) will double every 18-24 months while the price will remain constant. This means that computing power, growing exponentially over time, will continually pose more and more of a threat to modern cryptographic systems and to antiquated ones still in use, as it becomes cheaper and faster to break them.

This is especially relevant for cryptanalysis requiring intensive computing power, such as brute-force attacks (see Rule 8 below). See Rule 55 for an example of how Moore's Law made feasible a brute-force attack on a keylength that was previously considered secure against keysearch attacks.

#

C. Rule .

Classical Attack #1: Brute-Force Attack/Exhaustive Key search:

Mathematical Definition:

Let (x, y) denote the pair of plaintext and ciphertext, and let K = {k1 ,..., kκ} be the keyspace of all possible keys ki. A brute-force attack now checks for every ki ∈ K whether dki == x.

If the equality holds, a possible correct key is found; if not, proceed with the next key.

Explanation:

The testing of all possible keys in a given keyspace with the decryption function, to find the key that will produce the plaintext. This is akin to thinking of the cryptosystem as a black box, in which the only significant factor to decoding an encrypted message is the number of possible keys the message could have been created with.

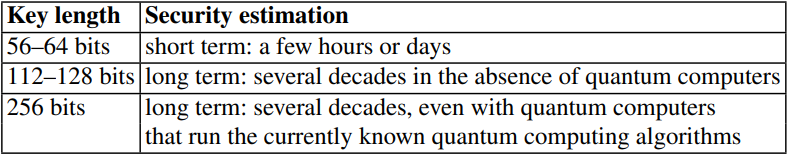

As shown in the illustration below, different keyspaces take different amounts of time to crack using brute-force. As such, only algorithms with a sufficiently large keyspace can be considered secure against brute-force, though not necessarily against any other form of attack.

A chart of the time it would take to crack keyspaces of various lengths using a brute-force attack.

As of 2024, the largest keyspace that can be searched in a relatively reasonable amount of time is 2^80. However, not all keybits are created equally: a 128-bit symmetric key provides roughly the same security as a 3072-bit RSA (asymmetric algorithm) key, as noted in Rule 6. For why this is, see Rule [[[.

Mathematical Definition:

Let (x, y) denote the pair of plaintext and ciphertext, and let K = {k1 ,..., kκ} be the keyspace of all possible keys ki. A brute-force attack now checks for every ki ∈ K whether dki == x.

If the equality holds, a possible correct key is found; if not, proceed with the next key.

Explanation:

The testing of all possible keys in a given keyspace with the decryption function, to find the key that will produce the plaintext. This is akin to thinking of the cryptosystem as a black box, in which the only significant factor to decoding an encrypted message is the number of possible keys the message could have been created with.

As shown in the illustration below, different keyspaces take different amounts of time to crack using brute-force. As such, only algorithms with a sufficiently large keyspace can be considered secure against brute-force, though not necessarily against any other form of attack.

A chart of the time it would take to crack keyspaces of various lengths using a brute-force attack.

As of 2024, the largest keyspace that can be searched in a relatively reasonable amount of time is 2^80. However, not all keybits are created equally: a 128-bit symmetric key provides roughly the same security as a 3072-bit RSA (asymmetric algorithm) key, as noted in Rule 6. For why this is, see Rule [[[.

#

C. Rule .

Classical Attack #2: Analytical Attacks:

The intelligent counterpart to 'brute'-force, Analytical Attacks examine the internal characteristics of the encryption function and pick apart weaknesses that could enable reconstruction of the plaintext message, such as Letter Frequency Analysis (for the Substitution Cipher, see Rule 10) and Differential Cryptanalysis (for Block and Stream Ciphers, see Rule [[[[).

There is no 'equation' for Analytical Attacks, because they are specific and unique to every cryptosystem (though some common characteristics can emerge between similar cryptosystems).

The intelligent counterpart to 'brute'-force, Analytical Attacks examine the internal characteristics of the encryption function and pick apart weaknesses that could enable reconstruction of the plaintext message, such as Letter Frequency Analysis (for the Substitution Cipher, see Rule 10) and Differential Cryptanalysis (for Block and Stream Ciphers, see Rule [[[[).

There is no 'equation' for Analytical Attacks, because they are specific and unique to every cryptosystem (though some common characteristics can emerge between similar cryptosystems).

I.V Generic Analytical Attacks.

# Ciphertext-only Attack: An attack in which the adversary only has knows the ciphertext.

# Known-plaintext Attack: In addition to the ciphertext, the adversary also knows some pieces of the plaintext (e.g., header information of an encrypted file or email).

# Chosen-plaintext Attack: An attack in which the adversary can choose the plaintext that is being encrypted and also has access to the corresponding ciphertext, found through possession of the decryption function (whether the attacker is aware of its internal workings or not). This attack is primarily used to find a key that is being reused in a communication, so that further ciphertexts encrypted with the key can be decrypted.

# Chosen-ciphertext Attack: An attack in which the adversary can choose ciphertexts and obtain the corresponding plaintexts, the goal being (typically) to recover the secret key.

II. Historical Ciphers & Modular Arithmetic.

II.I Substitution Cipher.

Because these ciphers do not operate on bits (and thus do not have keys structured in the form of binary strings with fixed lengths), the relation between keyspace and keybit-length as detailed in Rule 6 does not apply to these ciphers does not apply to these ciphers.

#

C. Rule .

Substitution Cipher

A historical cipher, operating purely on letters, in which every plaintext letter is replaced by a fixed ciphertext letter. It is just scrambling the letters, nothing more.

The Keyspace is 26!, or 2^88, as each plaintext letter that maps to a ciphertext letter decreases the remaining number of possible letters. Thus, a brute-force attack would be out of the question for modern computers.

Since the different letters of the English alphabet have different frequencies of appearance (see the image below), and these frequencies are preserved even after scrambling (just different letters will have the frequencies), Letter Frequency Analysis can be conducted as an attack on the substitution cipher, making cracking the cipher rather simple.

This is an example of a cipher/algorithm in which an Analytical Attack (see Rule 9) is most effective.

A generalized distribution of letters in the english language. In substitution ciphers, the frequencies remain the same, with only the letters that represent them changing. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

A historical cipher, operating purely on letters, in which every plaintext letter is replaced by a fixed ciphertext letter. It is just scrambling the letters, nothing more.

The Keyspace is 26!, or 2^88, as each plaintext letter that maps to a ciphertext letter decreases the remaining number of possible letters. Thus, a brute-force attack would be out of the question for modern computers.

Since the different letters of the English alphabet have different frequencies of appearance (see the image below), and these frequencies are preserved even after scrambling (just different letters will have the frequencies), Letter Frequency Analysis can be conducted as an attack on the substitution cipher, making cracking the cipher rather simple.

This is an example of a cipher/algorithm in which an Analytical Attack (see Rule 9) is most effective.

A generalized distribution of letters in the english language. In substitution ciphers, the frequencies remain the same, with only the letters that represent them changing. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

II.II Modular Arithmetic Basics.

#

C. Rule .

Modular Arithmetic:

Mathematical Definition:

(a, r, m) ∈ ℤ

m > 0

If m|(a − r), then a ≡ r mod m

ℤ = The set of all integers.

a = The chosen number.

r = The remainder.

m = The modulus, the highest possible number in the set.

'mod m' = The modulus operator / remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to m.

Explanation:

Since the bulk of cryptographic computations are performed in finite sets, special mathematical tools are needed. In particular, Modular Arithmetic is the basis for all modern cryptosystems, and many historical ones as well.

Modular arithmetic is a system of simplifying a number in terms of a given modulus, the highest number in a set. As shown in the mathematical definition, any chosen number greater than the modulus is rewritten using the modulus operator (a.k.a. the remainder operator) with respect to the difference between the number and any multiple (see Rule 12) of the modulus, known as the remainder.

The best example for understanding modular arithmetic is something most are already familiar with: time on a clock. On clocks, the highest number is 12, and going any higher just loops back to the beginning. In effect, a clock is a modular arithmetic system using a set of {1, 2, ... 12} with a modulus of 12. 13 hours, for example, would be represented as 1 mod 12, using the modulus operator as specified in the mathematical definition.

The process of finding the modular equivalent of a number (in relation to an already known modulus/set) is simple: divide the chosen number by the modulus, and find the remainder (see Rule 12). The remainder will then be placed as the coefficient in front of the modulus operator. All numbers smaller than the modulus are rendered ordinarily, without the mod operator. For example, the modular representation of 4 in the clock example (mod 12) is just 4.

Using modular representation is a bit jarring at first, as it effectively 'wraps' the chosen number around the modulus, but frequent use (as it is used in practically every cryptosystem) will make it second nature to the beginning cryptographer.

Mathematical Definition:

(a, r, m) ∈ ℤ

m > 0

If m|(a − r), then a ≡ r mod m

ℤ = The set of all integers.

a = The chosen number.

r = The remainder.

m = The modulus, the highest possible number in the set.

'mod m' = The modulus operator / remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to m.

Explanation:

Since the bulk of cryptographic computations are performed in finite sets, special mathematical tools are needed. In particular, Modular Arithmetic is the basis for all modern cryptosystems, and many historical ones as well.

Modular arithmetic is a system of simplifying a number in terms of a given modulus, the highest number in a set. As shown in the mathematical definition, any chosen number greater than the modulus is rewritten using the modulus operator (a.k.a. the remainder operator) with respect to the difference between the number and any multiple (see Rule 12) of the modulus, known as the remainder.

The best example for understanding modular arithmetic is something most are already familiar with: time on a clock. On clocks, the highest number is 12, and going any higher just loops back to the beginning. In effect, a clock is a modular arithmetic system using a set of {1, 2, ... 12} with a modulus of 12. 13 hours, for example, would be represented as 1 mod 12, using the modulus operator as specified in the mathematical definition.

The process of finding the modular equivalent of a number (in relation to an already known modulus/set) is simple: divide the chosen number by the modulus, and find the remainder (see Rule 12). The remainder will then be placed as the coefficient in front of the modulus operator. All numbers smaller than the modulus are rendered ordinarily, without the mod operator. For example, the modular representation of 4 in the clock example (mod 12) is just 4.

Using modular representation is a bit jarring at first, as it effectively 'wraps' the chosen number around the modulus, but frequent use (as it is used in practically every cryptosystem) will make it second nature to the beginning cryptographer.

# Cyclic Shift/Cyclical Shift: A fancy term essentially just denoting the usage of modular arithmetic in a particular context, with sets wrapping around once they reach an overflow value and whatnot.

#

C. Rule .

Modular Arithmetic: Computation of the Remainder.

Mathematical Definition:

(a, m) ∈ ℤ

a = (q × m) + r

Thus, a - (q × m) = r

ℤ = The set of all integers.

a = The chosen number.

q = The quotient, which produces a multiple of the modulus.

r = The remainder.

m = The modulus, the highest possible number in the set.

Explanation:

To find the remainder in a modular arithmetic system (see Rule 11) when only the chosen number and the modulus (a and m) are known, there is an exact, algorithmic definition. Note that there are two unknown variables in this equation - the quotient and the remainder (q & r). As such, the quotient will have to be determined first in order to find the remainder.

Any integer will work for the quotient (as a result of equivalence classes, which will be discussed later in Rule 13), but the preferred quotient will be the one that produces the preferred multiple (once multiplied with m), which will then produce the smallest positive remainder (known as the preferred remainder).

This is just a complicated way of saying that there is a particular quotient value that, when multiplied by the modulus, will produce a remainder with the chosen value that will allow for the modular representation (the Rule 11 equation with the modulus operator) to be in its most simplified form. The specificities of how this "preferred muliple" (formed by the quotient and the modulus) functions are elaborated upon below.

The preferred multiple of the modulus for finding the remainder is the greatest multiple lower than the chosen number, allowing for the remainder to be as small as possible: 0 ≤ r < m. Thus, the preferred multiple is mathematically the greatest (q × m) lower than a, which means finding the correct q given that m is a constant.

The difference between the preferred multiple and the chosen number is the smallest positive remainder, which is thus the preferred remainder.

For example, with a modulus of 12, 61 would be represented as 1 mod 12, since 61 has a remainder of 1 in relation to 60, the highest multiple of 12 below 61 (meaning that 60 is the preferred multiple). With respect to a clock, this means that 61 hours after 12 A.M. would be either 1 A.M. or 1 P.M., exactly which can be determined by mod 2 of the remainder (0 for A.M.; 1 for P.M.).

As stated before, any quotient/multiple of the modulus will work for the equation (if with a larger remainder) - see Rule 13, Equivalence Classes. The preferred multiple just allows for the most simplified version of a modular representation (see Rule 15), which will be the one used in practical applications of modular arithmetic. This preferred multiple is also the one that would be most easily determined by division, as described in Rule 11.

Mathematical Definition:

(a, m) ∈ ℤ

a = (q × m) + r

Thus, a - (q × m) = r

ℤ = The set of all integers.

a = The chosen number.

q = The quotient, which produces a multiple of the modulus.

r = The remainder.

m = The modulus, the highest possible number in the set.

Explanation:

To find the remainder in a modular arithmetic system (see Rule 11) when only the chosen number and the modulus (a and m) are known, there is an exact, algorithmic definition. Note that there are two unknown variables in this equation - the quotient and the remainder (q & r). As such, the quotient will have to be determined first in order to find the remainder.

Any integer will work for the quotient (as a result of equivalence classes, which will be discussed later in Rule 13), but the preferred quotient will be the one that produces the preferred multiple (once multiplied with m), which will then produce the smallest positive remainder (known as the preferred remainder).

This is just a complicated way of saying that there is a particular quotient value that, when multiplied by the modulus, will produce a remainder with the chosen value that will allow for the modular representation (the Rule 11 equation with the modulus operator) to be in its most simplified form. The specificities of how this "preferred muliple" (formed by the quotient and the modulus) functions are elaborated upon below.

The preferred multiple of the modulus for finding the remainder is the greatest multiple lower than the chosen number, allowing for the remainder to be as small as possible: 0 ≤ r < m. Thus, the preferred multiple is mathematically the greatest (q × m) lower than a, which means finding the correct q given that m is a constant.

The difference between the preferred multiple and the chosen number is the smallest positive remainder, which is thus the preferred remainder.

For example, with a modulus of 12, 61 would be represented as 1 mod 12, since 61 has a remainder of 1 in relation to 60, the highest multiple of 12 below 61 (meaning that 60 is the preferred multiple). With respect to a clock, this means that 61 hours after 12 A.M. would be either 1 A.M. or 1 P.M., exactly which can be determined by mod 2 of the remainder (0 for A.M.; 1 for P.M.).

As stated before, any quotient/multiple of the modulus will work for the equation (if with a larger remainder) - see Rule 13, Equivalence Classes. The preferred multiple just allows for the most simplified version of a modular representation (see Rule 15), which will be the one used in practical applications of modular arithmetic. This preferred multiple is also the one that would be most easily determined by division, as described in Rule 11.

#

C. Rule .

Equivalence Classes:

While 12 ≡ 3 mod 9, it is equally true that 12 ≡ 21 mod 9, and that 12 ≡ -6 mod 9. Although these remainders may not be the preferred remainder of 3 (see Rule 12), they all still return true in the Modular Arithmetic formula (see Rule 11):

12 ≡ 3 mod 9, 3 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−3)

12 ≡ 21 mod 9, 21 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−21)

12 ≡ −6 mod 9, −6 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−(−6))

The given remainder values can all be simplified down to their smallest possible positive number using the preferred multiple of the modulus, as detailed in Rule 12. Thus, all of these modular representations are inherently equal as they all have the same 'root' preferred remainder. The set of all remainder values that behave 'equivalently' for a particular modulus form what is known as an Equivalence Class, an infinite set/series of values.

For 3 mod 9, the equivalence class of r values is an infinite set, a partial series of which is as follows:

{..., -24, -15, -6, 3, 12, 21, 30, ...}

If any of these values were to be substituted in for r (3) in 3 mod 9, it would be equivalent, the same value, because of the mod operator.

Note: There are 'm' equivalence classes for each possible remainder (0 through m-1), which collectively contain all possible integers. The difference between any two neighboring values in an equivalence class will be the modulus, as shown above.

While 12 ≡ 3 mod 9, it is equally true that 12 ≡ 21 mod 9, and that 12 ≡ -6 mod 9. Although these remainders may not be the preferred remainder of 3 (see Rule 12), they all still return true in the Modular Arithmetic formula (see Rule 11):

12 ≡ 3 mod 9, 3 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−3)

12 ≡ 21 mod 9, 21 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−21)

12 ≡ −6 mod 9, −6 is a valid remainder since 9|(12−(−6))

The given remainder values can all be simplified down to their smallest possible positive number using the preferred multiple of the modulus, as detailed in Rule 12. Thus, all of these modular representations are inherently equal as they all have the same 'root' preferred remainder. The set of all remainder values that behave 'equivalently' for a particular modulus form what is known as an Equivalence Class, an infinite set/series of values.

For 3 mod 9, the equivalence class of r values is an infinite set, a partial series of which is as follows:

{..., -24, -15, -6, 3, 12, 21, 30, ...}

If any of these values were to be substituted in for r (3) in 3 mod 9, it would be equivalent, the same value, because of the mod operator.

Note: There are 'm' equivalence classes for each possible remainder (0 through m-1), which collectively contain all possible integers. The difference between any two neighboring values in an equivalence class will be the modulus, as shown above.

#

C. Rule .

Modular Reduction:

Because any value in an equivalence class acts the same with regard to the mod operator of a given modulus, then substitutions can be made in mathematical operations that use the modulus operator, simplifying them.

Take (13 × 16) - 8, with modulus 5. While the full number can be computed (200) and an answer derived from there (0 mod 5), that is lame and time-consuming. A much cooler, faster, 21st century means of solving the problem is to substitute in for each term the simplest member of their respective equivalence classes:

13 mod 5 has a remainder of 3, and so 3 is the simplest term.

16 mod 5 has a remainder of 1, and so 1 is the simplest term.

8 mod 5 has a remainder of 3, and so 3 is the simplest term.

Therefore, the same calculation can be performed with simply (3 × 1) - 3, which returns 0 mod 5, the same answer as before, but found much easier-ly.

Note that this substitution trick does not extend equally to all mathematical operations. Exponentials, for example, cannot be simplified with the modulus:

For the problem 3⁸ mod 7, the exponent '8' cannot be simplified down to 1 mod 7. Exponents simply cannot have the substitution performed, while the base can (as shown in the example below).

For all exponentials, simplification into smaller components (using the 2nd Holy Property of Exponents - see Math Rule 66) must be performed to simplify. For ex.: 3⁸ = (3²)⁴ = (9)⁴ = (2)⁴ = 16 mod 7 = 2 mod 7, which is the answer.

Operations where equivalence class substitutions are allowed:

Multiplication

Addition

Substraction

Operations where equivalence class substitutions are banned:

Exponentials (for the exponent itself, not including the base)

Division

Because any value in an equivalence class acts the same with regard to the mod operator of a given modulus, then substitutions can be made in mathematical operations that use the modulus operator, simplifying them.

Take (13 × 16) - 8, with modulus 5. While the full number can be computed (200) and an answer derived from there (0 mod 5), that is lame and time-consuming. A much cooler, faster, 21st century means of solving the problem is to substitute in for each term the simplest member of their respective equivalence classes:

13 mod 5 has a remainder of 3, and so 3 is the simplest term.

16 mod 5 has a remainder of 1, and so 1 is the simplest term.

8 mod 5 has a remainder of 3, and so 3 is the simplest term.

Therefore, the same calculation can be performed with simply (3 × 1) - 3, which returns 0 mod 5, the same answer as before, but found much easier-ly.

Note that this substitution trick does not extend equally to all mathematical operations. Exponentials, for example, cannot be simplified with the modulus:

For the problem 3⁸ mod 7, the exponent '8' cannot be simplified down to 1 mod 7. Exponents simply cannot have the substitution performed, while the base can (as shown in the example below).

For all exponentials, simplification into smaller components (using the 2nd Holy Property of Exponents - see Math Rule 66) must be performed to simplify. For ex.: 3⁸ = (3²)⁴ = (9)⁴ = (2)⁴ = 16 mod 7 = 2 mod 7, which is the answer.

Operations where equivalence class substitutions are allowed:

Multiplication

Addition

Substraction

Operations where equivalence class substitutions are banned:

Exponentials (for the exponent itself, not including the base)

Division

#

C. Rule .

When getting a result in modular arithmetic, always simplify down to the smallest positive member of the equivalence class (see Rule 13) for your final answer. Whether for a homework/test answer or for 'in-the-field' cryptography work, it is convention to use the most simplified version of the class.

II.III Integer Rings.

#

C. Rule .

Algebraic Modular Arithmetic:

Modular Arithmetic can be defined in the form of an integer ring:

The integer ring ℤm consists of the following characteristics:

1. The set ℤm = {0, 1, ..., m-1}

2. Two arithmetic operators, "+" and "×", hold for all (a, b, c, d) ∈ ℤm such that:

i) a + b ≡ c mod m

ii) a × b ≡ d mod m

There are many overshadowing rules that every ring has to fulfill, seen in the section "RULES OF THE RING" below.

Modular Arithmetic can be defined in the form of an integer ring:

The integer ring ℤm consists of the following characteristics:

1. The set ℤm = {0, 1, ..., m-1}

2. Two arithmetic operators, "+" and "×", hold for all (a, b, c, d) ∈ ℤm such that:

i) a + b ≡ c mod m

ii) a × b ≡ d mod m

There are many overshadowing rules that every ring has to fulfill, seen in the section "RULES OF THE RING" below.

# RULES OF THE RING:

These following rules hold true for all integer rings in general, not just those pertaining to modular arithmetic.

- The ring should be closed: if any two numbers from the set are multiplied or added together, the result must be in the ring. This is ensured by the modulus operator, which always pulls the number back into the set to a value below m.

- Addition and multiplication are associative properties: For all (a, b, c) ∈ ℤm, a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c, and a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c.

- Addition is commutative for all (a, b) ∈ ℤm: a + b = b + a.

- There is an additive neutral element, 0. For all elements a ∈ ℤm, it holds that a + 0 ≡ a mod m. It is used to define the additive inverse.

- The additive inverse always exists: for any element a in the ring, there is always a negative element '-a' such that a + (-a) ≡ 0 mod m, the neutral element.

- There is a multiplicative neutral element, 1: For all elements a ∈ ℤm, it holds that a × 1 ≡ a mod m. It is used to define the multiplicative inverse.

- The Multiplicative Inverse exists only for some elements: For a ∈ ℤ, the inverse a⁻¹ is defined such that a × a⁻¹ ≡ 1 mod m. The nature of most inverses and the reasons for their occasional nonexistence are outlined in the Inverse Rules - see Rule 17 & Rule 18.

If there exists an inverse for a, then, a rare usage of division in the modular ring becomes possible: the element a⁻¹ can be divided by, as a divisor, since b/a ≡ b × a⁻¹ mod m. - The distributive property holds for all ring operations. For all (a, b, c) ∈ ℤm, a × (b + c) = (a × b) + (a × c).

Addition:

Multiplication:

#

C. Rule .

Multiplicative Inverse Eligibility Test:

To determine if an inverse exists for a specific 'a' of a particular modulus (which, for a ring, is the highest value in the set), simply find the gcd (Greatest Common Divisor) of the two values:

If gcd(a, m) = 1, then there exists a⁻¹, and a & m are said to be "relatively prime", or "coprime".

If gcd(a, m) ≠ 1, then there does NOT exist a⁻¹.

If m is prime, then gcd(a, m) will always equal to 1, for all nonzero 'a' values, and thus every 'a' value will have an inverse in that ring. The inverse of an integer completely depends on the ring, and thus the modulus.

To determine if an inverse exists for a specific 'a' of a particular modulus (which, for a ring, is the highest value in the set), simply find the gcd (Greatest Common Divisor) of the two values:

If gcd(a, m) = 1, then there exists a⁻¹, and a & m are said to be "relatively prime", or "coprime".

If gcd(a, m) ≠ 1, then there does NOT exist a⁻¹.

If m is prime, then gcd(a, m) will always equal to 1, for all nonzero 'a' values, and thus every 'a' value will have an inverse in that ring. The inverse of an integer completely depends on the ring, and thus the modulus.

#

C. Rule .

Application of Multiplicative Inverses:

Finding the Multiplicative Inverse of 'a' has the following formula (as described in RULE OF THE RING #7):

a × a⁻¹ ≡ 1 mod m

Though the multiplicative inverse of a is literally shown as a⁻¹, it is almost never the actual reciprocal of a. The reason for this is simple: All reciprocals other than -1 and 1 are not integers, and are thus not included in the set (under part 1 of the ring definition given in Rule 16).

Take a = 5, for example. The supposed inverse '1/5' is incorrect in any context, because it is not included in the set. A different inverse must be found specific to the modulus. For example, if the modulus were 7, then (as the given values pass the multiplicative eligibility test of Rule 17) the true multiplicative inverse can be found:

5 × 5⁻¹ ≡ 1 mod 7

5 × 3 ≡ 1 mod 7

5⁻¹ = 3

As shown above, when used in regards to algebraic rings, the concept of an 'inverse' bears no relation to its common usage in representing reciprocals.

Finding the Multiplicative Inverse of 'a' has the following formula (as described in RULE OF THE RING #7):

a × a⁻¹ ≡ 1 mod m

Though the multiplicative inverse of a is literally shown as a⁻¹, it is almost never the actual reciprocal of a. The reason for this is simple: All reciprocals other than -1 and 1 are not integers, and are thus not included in the set (under part 1 of the ring definition given in Rule 16).

Take a = 5, for example. The supposed inverse '1/5' is incorrect in any context, because it is not included in the set. A different inverse must be found specific to the modulus. For example, if the modulus were 7, then (as the given values pass the multiplicative eligibility test of Rule 17) the true multiplicative inverse can be found:

5 × 5⁻¹ ≡ 1 mod 7

5 × 3 ≡ 1 mod 7

5⁻¹ = 3

As shown above, when used in regards to algebraic rings, the concept of an 'inverse' bears no relation to its common usage in representing reciprocals.

#

C. Rule .

Always, as a rule of life, write denominators as (x)⁻¹ (instead of as below a line). With the importance of the inverse operation, it is always critical to recognize all denominators as just being inverses of their values. 1/a = a⁻¹.

II.IV Shift/Caesar Cipher.

#

C. Rule .

Shift Cipher:

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, k) ∈ ℤ26

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ (x + k) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (y - k) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

k = The Key fed into the encryption and decryption functions. Here, it represents the number of times that the characters of the plaintext are shifted rightward, using the alphabet as the set. Variations may use an expanded set, including numbers and special characters.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26. Variations may use an expanded set, including numbers or special characters, in which case the '26' would change accordingly.

Explanation:

A simplified form or special case of the Substitution Cipher (Rule 10), the Shift Cipher (or Caesar Cipher) merely shifts every plaintext letter however many so positions rightward in the alphabet, wrapping around when it reaches the end (modular arithmetic!). This is occasionally known as the "ROT" Cipher (short for "rotate"), and the most well-known example is ROT13, which shifts rightward precisely halfway through the alphabet.

As a generic example, with a key of 1, some shifts would be as follows:

a -> b

b -> c

...

z -> a

As shown, once the alphabet reaches letter (26 - k) + 1, or the position in the ring ℤ26 (26 - k) (since the set begins at 0), the shift returns to the front of the alphabet.

It should be obvious to all this is an extremely unsecure cryptosystem, with a keyspace of only 26. It is vulnerable to both letter frequency analysis (previously explained in relation to Substitution Ciphers - see Rule 10) and brute-force attacks (see Rule 8).

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, k) ∈ ℤ26

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ (x + k) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (y - k) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

k = The Key fed into the encryption and decryption functions. Here, it represents the number of times that the characters of the plaintext are shifted rightward, using the alphabet as the set. Variations may use an expanded set, including numbers and special characters.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26. Variations may use an expanded set, including numbers or special characters, in which case the '26' would change accordingly.

Explanation:

A simplified form or special case of the Substitution Cipher (Rule 10), the Shift Cipher (or Caesar Cipher) merely shifts every plaintext letter however many so positions rightward in the alphabet, wrapping around when it reaches the end (modular arithmetic!). This is occasionally known as the "ROT" Cipher (short for "rotate"), and the most well-known example is ROT13, which shifts rightward precisely halfway through the alphabet.

As a generic example, with a key of 1, some shifts would be as follows:

a -> b

b -> c

...

z -> a

As shown, once the alphabet reaches letter (26 - k) + 1, or the position in the ring ℤ26 (26 - k) (since the set begins at 0), the shift returns to the front of the alphabet.

It should be obvious to all this is an extremely unsecure cryptosystem, with a keyspace of only 26. It is vulnerable to both letter frequency analysis (previously explained in relation to Substitution Ciphers - see Rule 10) and brute-force attacks (see Rule 8).

#

C. Rule .

Vigenère Cipher

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, k, l) ∈ ℤ26

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ (xi + ki mod l) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (yi - ki mod l) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

k = The Key/codeword fed into the encryption and decryption functions, which, like the plaintext, is a series of letters (represented by their numerical value, 0-25) that are referred to by their i position. The key may have less, more, or the same number of characters as the plaintext (see 'l').

i = The position in the string of the plaintext, and regardless of the length of l (as a result of the mod operator), the key.

mod l = 'l' represents the length of the codeword. The mod operator functions such that if there are less characters in the codeword than in the plaintext, then the codeword characters will wrap around so that they can continue being used to produce ciphertext indefinitely.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26.

Explanation:

A mere variation of the Shift cipher, in which the shift for each letter is determined by a secret codeword 'c', which has 'l' characters. Each character in the code word c represents a number of shifts rightward according to the numerical value. For example, 'a' would represent a rightward shift of zero places, while 'z' would represent a shift of 25 places.

The encryption function works as follows: Each character in the plaintext string 'x' is applied a rightward shift according to its respective letter (identical position) in the key text. This is a cyclic shift (see definition), for if the addition of the key-character value produces a number greater than 26, then the alphabet will wrap around to the beginning. For example, the plaintext character 'z' plus the codeword character 'b' will produce the ciphertext character 'a'. An interesting side-effect of this is that if the keytext is just a string of 'a' ("aaaaaaaa"), then the ciphertext will be identical to the plaintext.

The decryption function, of course, is just the opposite of the encryption function, moving each character of the ciphertext backward by the value in the positional counterpart of the code word 'c'.

Because of the way the equation is written, the key does not necessarily need to have the same number of characters as the plaintext. The mod operator on the 'l', the number of characters in the codeword, causes any short codeword to wrap around to account for any longer plaintext strings. For example, for a plaintext of "lingonberry" and a codeword of "sup", the mod operator would cause the codeword to effectively become "supsupsupsu", accounting for each character of the plaintext. Likewise, any codeward longer than the plaintext has any characters beyond the length of the plaintext ignored.

For each value of i within l, the characters of the codeword are mathematically denoted as {c0, c1, ..., cl - 1}, and the keys are similarly represented as {k0, k1, ..., kl - 1}.

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, k, l) ∈ ℤ26

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ (xi + ki mod l) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (yi - ki mod l) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

k = The Key/codeword fed into the encryption and decryption functions, which, like the plaintext, is a series of letters (represented by their numerical value, 0-25) that are referred to by their i position. The key may have less, more, or the same number of characters as the plaintext (see 'l').

i = The position in the string of the plaintext, and regardless of the length of l (as a result of the mod operator), the key.

mod l = 'l' represents the length of the codeword. The mod operator functions such that if there are less characters in the codeword than in the plaintext, then the codeword characters will wrap around so that they can continue being used to produce ciphertext indefinitely.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26.

Explanation:

A mere variation of the Shift cipher, in which the shift for each letter is determined by a secret codeword 'c', which has 'l' characters. Each character in the code word c represents a number of shifts rightward according to the numerical value. For example, 'a' would represent a rightward shift of zero places, while 'z' would represent a shift of 25 places.

The encryption function works as follows: Each character in the plaintext string 'x' is applied a rightward shift according to its respective letter (identical position) in the key text. This is a cyclic shift (see definition), for if the addition of the key-character value produces a number greater than 26, then the alphabet will wrap around to the beginning. For example, the plaintext character 'z' plus the codeword character 'b' will produce the ciphertext character 'a'. An interesting side-effect of this is that if the keytext is just a string of 'a' ("aaaaaaaa"), then the ciphertext will be identical to the plaintext.

The decryption function, of course, is just the opposite of the encryption function, moving each character of the ciphertext backward by the value in the positional counterpart of the code word 'c'.

Because of the way the equation is written, the key does not necessarily need to have the same number of characters as the plaintext. The mod operator on the 'l', the number of characters in the codeword, causes any short codeword to wrap around to account for any longer plaintext strings. For example, for a plaintext of "lingonberry" and a codeword of "sup", the mod operator would cause the codeword to effectively become "supsupsupsu", accounting for each character of the plaintext. Likewise, any codeward longer than the plaintext has any characters beyond the length of the plaintext ignored.

For each value of i within l, the characters of the codeword are mathematically denoted as {c0, c1, ..., cl - 1}, and the keys are similarly represented as {k0, k1, ..., kl - 1}.

II.V Affine Cipher.

#

C. Rule .

Affine Cipher:

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, a, b) ∈ ℤ26

K = (a, b)

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ ((a × x) + b) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (a⁻¹ × (y - b)) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

K = The key, which has been split into two parts: a and b.

a = The multiplied value of the key. The number of possible 'a' values is limited by the necessity of the inverse (for the decryption function), as explained below.

a⁻¹ = The inverse of a, necessary for the decryption function.

b = The "shift parameter" value of the key, used only in addition and subtraction operations. There are 26 possible values for b, explained below.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26.

Explanation:

The Affine Cipher is an attempted improvement of the shift cipher, done by complicating the encryption function through the addition of multiple parameters. However, it is still extremely easy to break. The affine cipher is performed by splitting the key into two parts:

K = (a, b)

The number of possible b values in the system is 26, as it is merely the shift parameter (as shown in the definition equations).

The number of possible a values, as a result of the inverse in the decryption function, is limited by the condition explicated in the multiplicative inverse eligibility test of Rule 17, with m being 26: only when gcd(a, 26) = 1 is 'a' an inverse, and thus contributive to the number of possible values. Counting all possible values of a (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, ...), all odd numbers 1-26 other than 13, produces an end result of 12 possible 'a' values.

The keyspace, being (#a) × (#b), is therefore 312. This remains very easy to break using a brute-force attack (see Rule 8).

Furthermore, letter frequency also remains preserved (since every instance of a particular plaintext character will be converted into the same corresponding ciphertext character, despite the minute differences in the encryption function), so a letter frequency analysis attack is also applicable.

Though multiple encryption (i.e., running the ciphertext produced by encryption function back into the encryption function to encrypt it again) will not increase the security of an affine cipher, it will for other ciphers, such as the Data Encryption Standard (see Rule 48).

Mathematical Definition:

(x, y, a, b) ∈ ℤ26

K = (a, b)

Encryption: ek(x) ≡ ((a × x) + b) mod 26

Decryption: dk(y) ≡ (a⁻¹ × (y - b)) mod 26

x = Plaintext message.

y = Ciphertext.

K = The key, which has been split into two parts: a and b.

a = The multiplied value of the key. The number of possible 'a' values is limited by the necessity of the inverse (for the decryption function), as explained below.

a⁻¹ = The inverse of a, necessary for the decryption function.

b = The "shift parameter" value of the key, used only in addition and subtraction operations. There are 26 possible values for b, explained below.

ℤ26 = A ring of the first 26 integers (including 0), matching the 26 characters of the alphabet. See Subsection II.III for an explanation of rings.

ek(x) = Encryption function, a mathematical formula that converts x into y.

dk(y) = Decryption function, a mathematical formula that converts y into x.

mod 26 = The modulus/remainder operator, which represents the usage of modular arithmetic, with all numbers represented by their remainder with respect to 26.

Explanation:

The Affine Cipher is an attempted improvement of the shift cipher, done by complicating the encryption function through the addition of multiple parameters. However, it is still extremely easy to break. The affine cipher is performed by splitting the key into two parts:

K = (a, b)

The number of possible b values in the system is 26, as it is merely the shift parameter (as shown in the definition equations).

The number of possible a values, as a result of the inverse in the decryption function, is limited by the condition explicated in the multiplicative inverse eligibility test of Rule 17, with m being 26: only when gcd(a, 26) = 1 is 'a' an inverse, and thus contributive to the number of possible values. Counting all possible values of a (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, ...), all odd numbers 1-26 other than 13, produces an end result of 12 possible 'a' values.

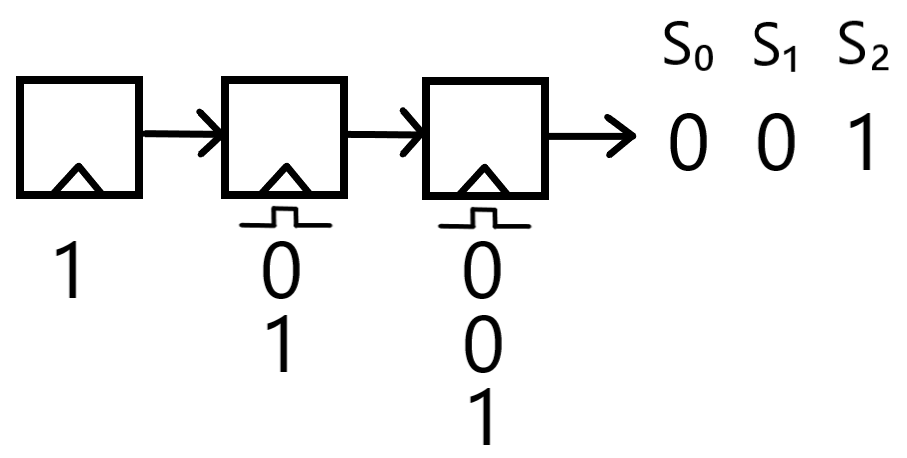

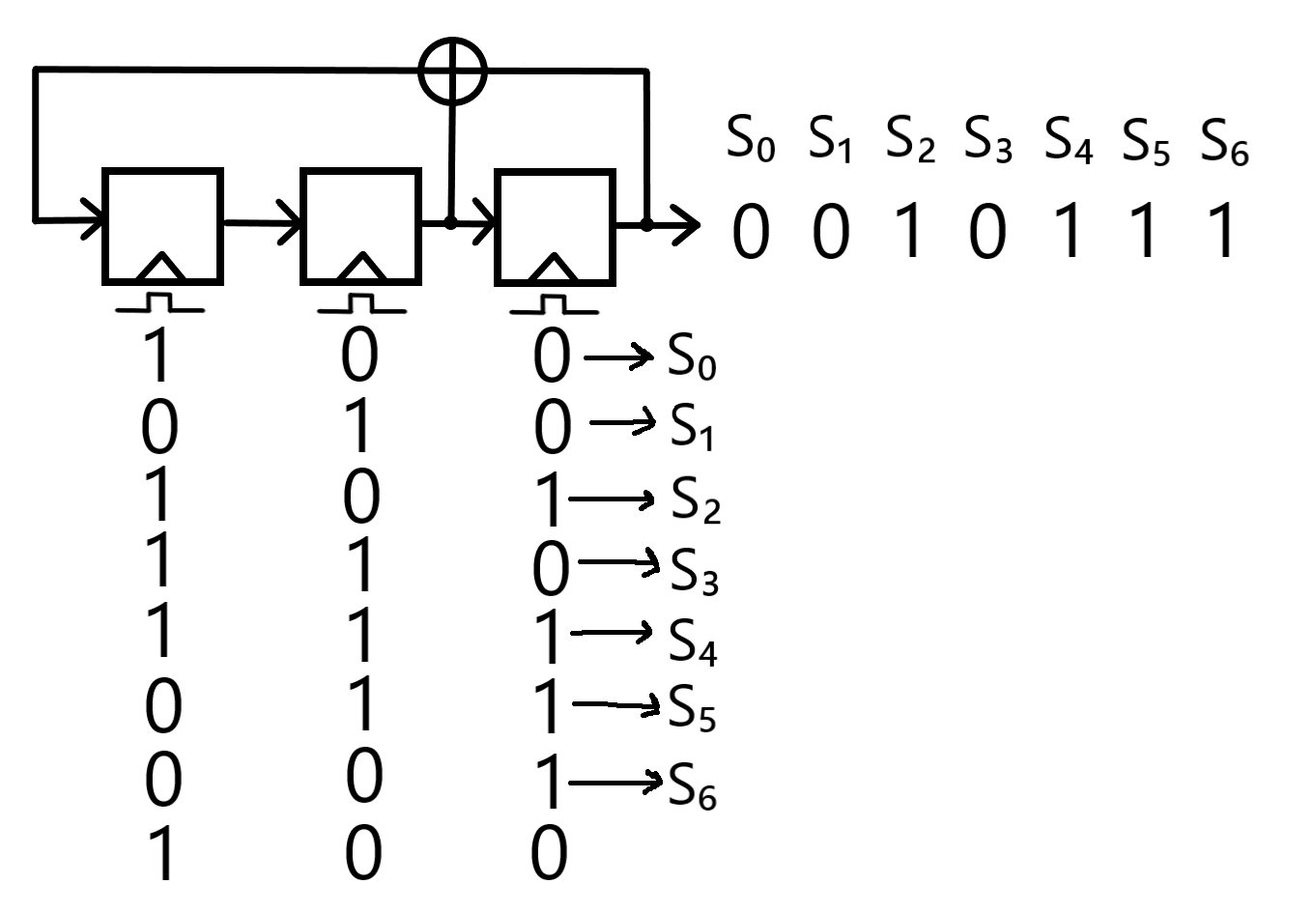

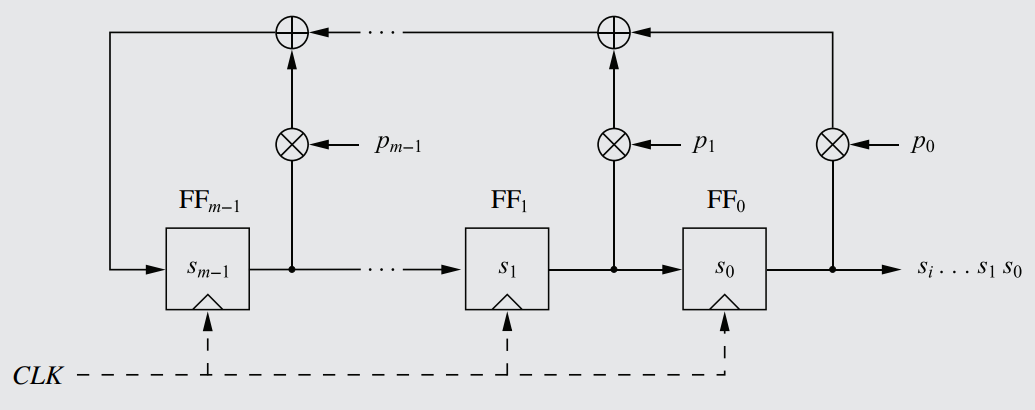

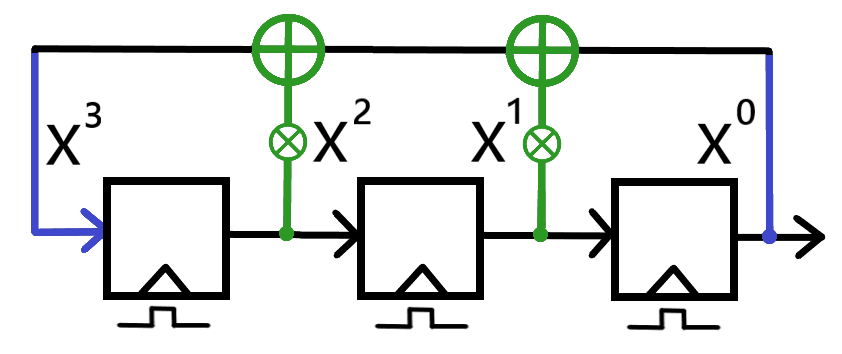

The keyspace, being (#a) × (#b), is therefore 312. This remains very easy to break using a brute-force attack (see Rule 8).