These are my complete notes for Domain and Symmetricality in Precalculus.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Domain and Symmetricality (Precalculus)

VII. Domain and Symmetricality.

#

Rule .

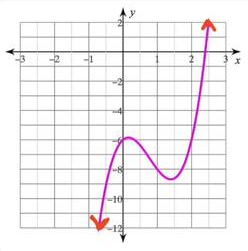

As is known of Domain and Range, the Domain is all the possible x-values a function covers while Range is all the possible y-values. Specifically, when combining Domain and Range with interval notation, Domain goes Left to Right while Range goes Down to Up. When you have a connected line graph that has no end, both ends stretching into infinity, both the domain and range are (-∞, ∞). This is for graphs that show as follows, with no asymptotes:

A graph, x³, what has a domain and range of negative infinity to positive infinity. Courtesy of Study.com.

There can be graphs that can show disconnected lines, where functions like so:

A graph with a multitude of discontinuities. Courtesy of Ximera.

show a puzzle to figure out what is Domain and Range, while other graphs can also use tons of dots at important points to represent whether a high/low point is included in the line. For example, in the given graph, because the highest point of the left part is an empty circle, then that point unincluded in the leftmost interval. The full interval notation would be (-8, -3) ∪ [-1, 5) ∪ (5, 8].

A graph, x³, what has a domain and range of negative infinity to positive infinity. Courtesy of Study.com.

There can be graphs that can show disconnected lines, where functions like so:

A graph with a multitude of discontinuities. Courtesy of Ximera.

show a puzzle to figure out what is Domain and Range, while other graphs can also use tons of dots at important points to represent whether a high/low point is included in the line. For example, in the given graph, because the highest point of the left part is an empty circle, then that point unincluded in the leftmost interval. The full interval notation would be (-8, -3) ∪ [-1, 5) ∪ (5, 8].

#

Rule .

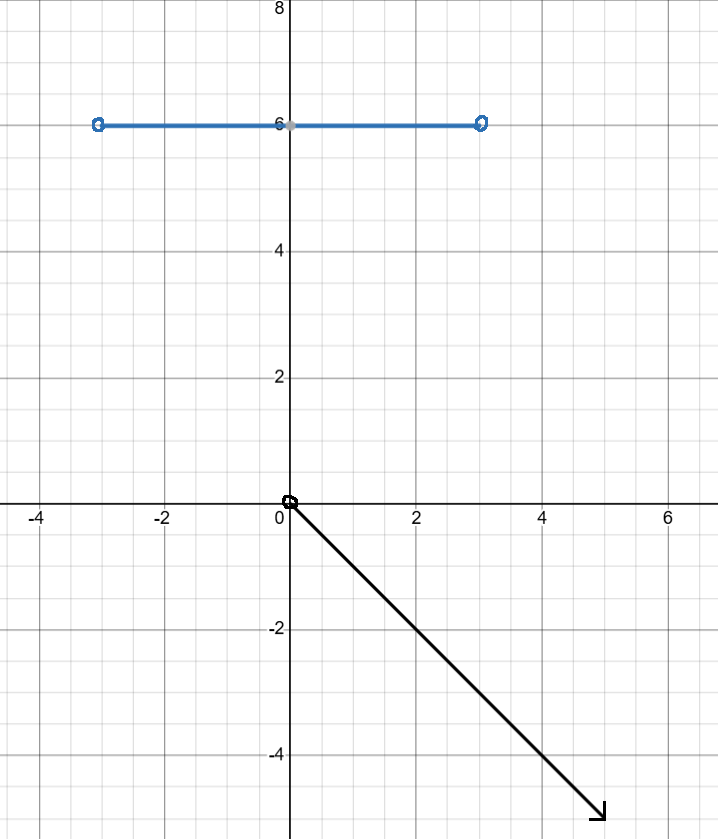

When you have a disconnected line graph, you may see that there is either a vertical or horizontal flat line. If the flat follows its respective register, such as a flat line following the x-axis when you're writing domain, no problem. But when you come across the same line while writing range, there is a special way of writing it: For a graph like this -

A graph of y = 6 {-3 < x < 3} and y = -x {0 < x}. Made using Desmos.

the first part of the interval notation would be (-∞, -2) ∪, with the down-to-up rule and all, but the second part would be represented as [6]. For either Domain or Range, brackets or parenthesis on a single digit means flat.

A graph of y = 6 {-3 < x < 3} and y = -x {0 < x}. Made using Desmos.

the first part of the interval notation would be (-∞, -2) ∪, with the down-to-up rule and all, but the second part would be represented as [6]. For either Domain or Range, brackets or parenthesis on a single digit means flat.

#

Rule .

The y-intercept is found by plugging in 0 for x, f(0). The x-intercept is found by plugging in 0 for y, "0 = ax² + bx + c". X-intercept are also known as the "zeroes" and "roots" of the function.

#

Rule .

There is symmetry test that can be conducted for every axis, x, y, and origin.

In relation to the x-axis:

A sideways absolute value function. Made using Desmos.

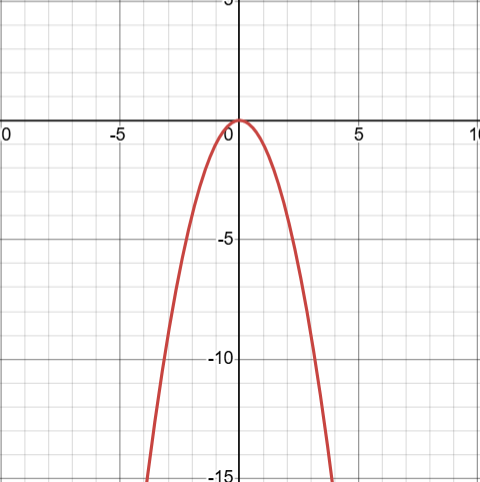

In relation to the y-axis:

y = -x². Made using Desmos.

In relation to the origin:

y = x³. Made using Desmos.

For the origin, fold first on x and then on y. To discover algebraically if it is symmetrical on any axis, you must plug in a negative for whichever vairable you feel the equation may be symmetrical for:

X-Axis: (x, y) = (x, -y)

Y-Axis: (x, y) = (-x, y)

Origin: (x, y) = (-x, -y)

In general, for equations like x = y² - 3 or whatnot, the variable that has the square is immune to becoming negative because of the automatic squaring, so it is highly likely in said situations that a shortcut can be taken to find what axis the equation is symmetrical on. However, it is always safer to plug in the negative for each possibility to discern whether the less obvious possibility is symmetrical as well. Multiple tests should be performed if you are not sure, in order to make sure that your first test was not just a coincidence.

In relation to the x-axis:

A sideways absolute value function. Made using Desmos.

In relation to the y-axis:

y = -x². Made using Desmos.

In relation to the origin:

y = x³. Made using Desmos.

For the origin, fold first on x and then on y. To discover algebraically if it is symmetrical on any axis, you must plug in a negative for whichever vairable you feel the equation may be symmetrical for:

X-Axis: (x, y) = (x, -y)

Y-Axis: (x, y) = (-x, y)

Origin: (x, y) = (-x, -y)

In general, for equations like x = y² - 3 or whatnot, the variable that has the square is immune to becoming negative because of the automatic squaring, so it is highly likely in said situations that a shortcut can be taken to find what axis the equation is symmetrical on. However, it is always safer to plug in the negative for each possibility to discern whether the less obvious possibility is symmetrical as well. Multiple tests should be performed if you are not sure, in order to make sure that your first test was not just a coincidence.

#

Rule .

There are two ways of checking whether an equation has a symmetricality in any way: Numerically and Algebraically. Numerically, you would plug in actual numbers for x and y and see what the equation would simplify to normally as a control group. For example, y = -x² + 6 is simplified to y = x² + 6. From there, plugging in (2, 2) resolves the equation to 2 = 10. This is the answer to be expected for any symmetry check to be correct - differing sides. Checking the Y-axis, for example, means plugging in (-2, 2), equal to 2 = (-2)² + 6. Simplifying this returns, once again, 2 = 10. These results mean that symmetry hath been confirmed. To check algebraically is much simplier, you need not plug in any values but the exact negativized variables from the original equation - E.g., plugging in (-x, y) for y = - (-x)² +6. Since the outer negative remains as before, symmetry has been proven both ways.

#

Rule .

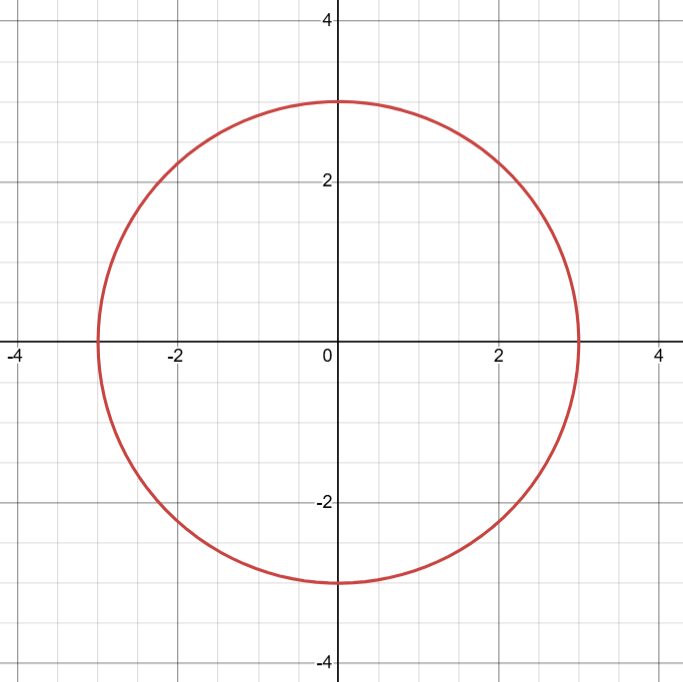

A perfect circle centered around the origin, like so:

A perfect circle. Made using Desmos.

would be symmetrical by both the x, y, and origin axis. Both the x and the y would be squared in the equation: (x+h)² + (y+k)² = r².

A perfect circle. Made using Desmos.

would be symmetrical by both the x, y, and origin axis. Both the x and the y would be squared in the equation: (x+h)² + (y+k)² = r².

#

Rule .

For the symmetries, there are general "odd" and "evens" that can be applied to the symmetry of an equation:

Symmetry in respect to X-Axis: Odd

Symmetry in respect to Y-Axis: Even

f(-x) = -f(x): Odd (Opposite)

f(-x) = f(x): Even (Same)

Apart from the application of the symmetries, this is a return to Alebra 2, as the x plugged in (checking the Y-axis), gives three possibilities:

Odd, if the returned f(x) is equal to the opposite of the original, Even, if the f(x) is the same, and Neither, for those in between.

Symmetry in respect to X-Axis: Odd

Symmetry in respect to Y-Axis: Even

f(-x) = -f(x): Odd (Opposite)

f(-x) = f(x): Even (Same)

Apart from the application of the symmetries, this is a return to Alebra 2, as the x plugged in (checking the Y-axis), gives three possibilities:

Odd, if the returned f(x) is equal to the opposite of the original, Even, if the f(x) is the same, and Neither, for those in between.