This is the first part of my complete notes for Electromagnetism, covering topics of Electrostatics such as Electric Charge, the Law of Electric Force, Conduction/Induction, Electric Fields, Electric Flux, Gauss's Law, and more.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Electromagnetism, Part 1: Electrostatics

Table Of Contents

XII. Law of Electric Force.

XII.I Electric Charge.

The character 'q' is used to denote the net charge on an object.

#

P. Rule .

The 'Coulomb' is the SI unit for Electric Charge. Specifically, it is defined as the "amount of electric charge transported by a current of one ampere flowing for one second" (see definitions of each new term, they are gone over in more depth later on).

By itself, a Coulomb is a huge amount of charge - charged particles like protons and electrons have electric charges many orders of magnitude smaller than a single Coulomb. Two objects, each with one Coulomb of charge, located one meter apart, experience an electric force (see Subsection XII.III) of roughly nine billion Newtons.

By itself, a Coulomb is a huge amount of charge - charged particles like protons and electrons have electric charges many orders of magnitude smaller than a single Coulomb. Two objects, each with one Coulomb of charge, located one meter apart, experience an electric force (see Subsection XII.III) of roughly nine billion Newtons.

# Excess Charge: The state of an object being more positively or negatively charged due to a lack or oversupply of negatively-charged electrons, the movement of which can be facilitated by rubbing objects together (charging by friction). Since positive ions are fixed in place, an object can only change in charge through the removal or addition of negative charges.

An "excess positive charge" is slang for an electron deficit, while an "excess negative charge" means an oversupply of electrons.

Note that the excess charge is effectively the total charge of the object, considering how an object without excess charge is considered to have a net-zero charge (neutral).

# Law of Charges:

Opposite charges attract, while like charges repel.

Example: Rubbing a balloon against one's hair will cause the electrons to move from the hair to the balloon (a transfer faciliated by rubbing), causing the balloon to stick to the hair. Furthermore, since each hair will become more positively-charged, they will repel one another, causing one's hair to stick up and separate.

XII.II Basics of Atomic Physics.

#

P. Rule .

An atom is the smallest unit of matter retaining the chemical properties of its element. It is composed of a dense nucleus with Protons and Neutrons, and surrounded by orbitals of Electrons.

Electrons & Protons are small particles (e.g., specks of mass) that carry an electric charge with a magnitude of ~1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs, which is referred to as the "Elementary Charge". Protons are positively charged, while electrons are negatively charged.

Electrons are elementary particles, indivisible by nature, while protons and neutrons are composed of quarks, the REAL smallest particles. Specifically, the proton has two up quarks and one down quark.

The up quark has a charge of +(2/3)e, while the down quark has the charge -(1/3)e. Thus, the net quark of a proton is +e.

The neutron, being composed of one up quark and two down quarks, has a net charge of 0. If this were not the case, the neutron would not be electrically neutral, and the nucleus of an atom would tear apart as the protons would repel from one another without the stabilizing force of the neutrons.

The electron, being an elementary particle (defined below), just has a net charge of -e.

Electrons & Protons are small particles (e.g., specks of mass) that carry an electric charge with a magnitude of ~1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs, which is referred to as the "Elementary Charge". Protons are positively charged, while electrons are negatively charged.

Electrons are elementary particles, indivisible by nature, while protons and neutrons are composed of quarks, the REAL smallest particles. Specifically, the proton has two up quarks and one down quark.

The up quark has a charge of +(2/3)e, while the down quark has the charge -(1/3)e. Thus, the net quark of a proton is +e.

The neutron, being composed of one up quark and two down quarks, has a net charge of 0. If this were not the case, the neutron would not be electrically neutral, and the nucleus of an atom would tear apart as the protons would repel from one another without the stabilizing force of the neutrons.

The electron, being an elementary particle (defined below), just has a net charge of -e.

# Elementary Charge: An electrical charge of 1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs, the standard charge of Protons and Electrons and the smallest charge recorded on an isolated particle (quarks aren't isolated). Represented as 'e'.

# MElectron (Electron Mass): 9.11 × 10⁻³¹ kg.

# MProton (Proton Mass): 1.67 × 10⁻²⁷ kg. This is over 1800x greater than the mass of an electron.

#

P. Rule .

There is an equation relating net charge and elementary charge (or any quantifiable proportion of elementary charge), useful for determining how many excess charge carriers it would take for a specific net charge to be achieved:

q = n × e

q = Net charge on an object.

n = Excess number of charge carriers (protons or electrons or whatever - it just has to be ONE of them).

e = The Elementary Charge Constant.

q = n × e

q = Net charge on an object.

n = Excess number of charge carriers (protons or electrons or whatever - it just has to be ONE of them).

e = The Elementary Charge Constant.

#

P. Rule .

Charge is quantized, meaning that it must come in discrete quantities, integer multiples of the elementary charge. This is because the 'net charge' of an object is the product of having more or fewer charged particles, and thus only multiples of the elementary charge are possible (since elementary particles are indivisible).

Using the net/elementary charge relation (see Rule 160), one can find that it is impossible for an object to have a net negative charge of 2.00 × 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs, as such a net force would require 1.25 electrons, violating quantization.

Using the net/elementary charge relation (see Rule 160), one can find that it is impossible for an object to have a net negative charge of 2.00 × 10⁻¹⁹ Coulombs, as such a net force would require 1.25 electrons, violating quantization.

#

P. Rule .

When the atoms of a conductor form a solid, some of their outermost (and most loosely held) electrons become free to wander about within the solid, leaving behind positively charged atoms (positive ions). These wandering electrons are known as conduction electrons. There are practically no free electrons in a nonconductor, since those electrons are tightly bound to their atoms.

Knowledge of the "mobility of charge" within conductors, and conductors alone, is fundamental for comprehending concepts in Electric Field and Charge-Flux Law type questions - see Rule 170.

Knowledge of the "mobility of charge" within conductors, and conductors alone, is fundamental for comprehending concepts in Electric Field and Charge-Flux Law type questions - see Rule 170.

XII.III Electric Force.

# Electroscope: An instrument for demonstrating electric charge. They take several forms, but generally have some place where an isolated charge (protected by some insulator, like glass) is held.

#

P. Rule .

Law of Electric Force (Coulomb's Law) (8): VECTOR.

Units: Newtons.

Equation:

Fe = (k × q1 × q2) / (r²)

Fe = The magnitude of the electric force that exists between two charged particles.

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

q1 = The net charge on object 1, measured in Coulombs.

q2 = The net charge on object 2, measured in Coulombs.

r = The distance between the centers of charge of the two objects.

Definition: Coulomb's Law, hereafter referred to as the Law of Electric Force, enables one to find the magnitude of the Electric Force with respect to two particles.

Note that this equation looks very similar to the Universal Law of Gravitation (see Rule 140). Accordingly, k (the Coulomb constant) functions similar to G (the Gravitational constant), being equal to (N × m²) / (a particular composition property of mass)². Clearly, since the Coulomb constant is 20 orders of magnitude stronger than the Gravitational constant, the Electric Force between objects is much more powerful than their Gravitational attraction. Fe >>> Fg.

If the calculated Electric Force has a Negative Value, then it is an attractive force. If the Electric Force has a Positive Value, then it is a repulsive force. This is quite obvious upon momentary consideration - a negative and a positive charge will always produce a negative, and thus attractive force, which matches the Law of Charges that opposite's attract. Thus also follows for repulsive like charges.

Units: Newtons.

Equation:

Fe = (k × q1 × q2) / (r²)

Fe = The magnitude of the electric force that exists between two charged particles.

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

q1 = The net charge on object 1, measured in Coulombs.

q2 = The net charge on object 2, measured in Coulombs.

r = The distance between the centers of charge of the two objects.

Definition: Coulomb's Law, hereafter referred to as the Law of Electric Force, enables one to find the magnitude of the Electric Force with respect to two particles.

Note that this equation looks very similar to the Universal Law of Gravitation (see Rule 140). Accordingly, k (the Coulomb constant) functions similar to G (the Gravitational constant), being equal to (N × m²) / (a particular composition property of mass)². Clearly, since the Coulomb constant is 20 orders of magnitude stronger than the Gravitational constant, the Electric Force between objects is much more powerful than their Gravitational attraction. Fe >>> Fg.

If the calculated Electric Force has a Negative Value, then it is an attractive force. If the Electric Force has a Positive Value, then it is a repulsive force. This is quite obvious upon momentary consideration - a negative and a positive charge will always produce a negative, and thus attractive force, which matches the Law of Charges that opposite's attract. Thus also follows for repulsive like charges.

# Attractive Force: A force that pulls entities together, whether masses or charges.

# Repulsive Force: A force that pushes entities apart.

# Point Charge: An object with zero size (an infinitely small dot) that carries an electric charge. This can be generalized to any object whose mass is negligible compared to its charge. It is the Electric equivalent to a 'point mass', in that a particular charge is concentrated upon a single particle/point in space for the purpose demonstrating physical properties.

# MicroCoulombs (μC): One one millionth of a Coulomb. E.g., 1 × 10⁻⁶ C. Occasionally misstated as "Myu Coulombs", "Myu-Coulombs", etc.

# NanoCoulombs (nC): One one billionth of a Coulomb. E.g., 1 × 10⁻⁹ C.

# PicoCoulombs (pC): One one trillionth of a Coulomb. E.g., 1 × 10⁻¹² C.

#

P. Rule .

With charges, the fundamental concept to understand in applying the Law of Electric Force is that in order to derive any useful information (depending on the question, but in general), you must determine the effect of the electric force on the individual point charges. Specifically, you must be able to determine the direction the charges will move in as a result of the force.

The Law of Electric Force determines the repulsive or attractive force acting on both charges, since they are a Newton's Law Force Pair (see Rule 74). However, in addition, you must utilize this information to determine the direction of the movement of each charge. If you have a proton on the left and an electron on the right, the proton will move rightward and the electron leftward as they attract toward one another. If you have two electrons, they will move in opposite directions away from one another.

The Law of Electric Force determines the repulsive or attractive force acting on both charges, since they are a Newton's Law Force Pair (see Rule 74). However, in addition, you must utilize this information to determine the direction of the movement of each charge. If you have a proton on the left and an electron on the right, the proton will move rightward and the electron leftward as they attract toward one another. If you have two electrons, they will move in opposite directions away from one another.

# Permittivity of Free Space:

There is a concept known as Electric Permittivity that is discussed in Section XVI, Rule 212. It is an attribute that fluctuates in value from problem to problem according to its equation. It essentially measures the Polarization (Rule 169) of a specific type of material (a dielectric, see Rule 216), and will be discussed more fully at a later time.

What can be revealed right now, and what will become fundamental for future sections, is the "Permittivity of Free Space", a constant value that measures how dense an electric field (in relation to an electric charge) will be "permitted" to form within a vacuum. Thus, all equations that use the constant imply that the electric field is being formed within a vacuum.

The Permittivity of Free Space is referred to as "Epsilon Naught" verbally, and has the following value:

ε0 = 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

This little constant will be used everywhere. It will become ubiquitous in electromagnetism. You will forget you ever lived without it, that there ever existed a time that it was not a fundamental part of your existence, and you will feel closer to it with each passing problem.

#

P. Rule .

Coulomb's constant: SCALAR (a constant).

Units: (C²) / (N × m²), using Columbs, Newtons, and Meters.

Equation:

k = (1 / 4πε0)

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

ε0 = "Epsilon Naught", The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

Definition: The Coulomb Constant, 'k', 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²), used in such equations as the Law of Electric Force (see Rule 163) and all its applications, has a special fixed relationship with another constant. This other constant is the permittivity constant, also just known as the permittivity of free space (described above).

This equation, of course, can be substituted in for 'k' wherever applicable. Furthermore, ε0 itself, as described in the "Permittivity of Free Space" blue section above, appears in several equations by itself, most notably the Charge-Flux Law (see Rule 188). The reasons for the usage of Coulomb's Constant at all is a matter of antiquated historical decisioning that we have to live with today.

Units: (C²) / (N × m²), using Columbs, Newtons, and Meters.

Equation:

k = (1 / 4πε0)

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

ε0 = "Epsilon Naught", The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

Definition: The Coulomb Constant, 'k', 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²), used in such equations as the Law of Electric Force (see Rule 163) and all its applications, has a special fixed relationship with another constant. This other constant is the permittivity constant, also just known as the permittivity of free space (described above).

This equation, of course, can be substituted in for 'k' wherever applicable. Furthermore, ε0 itself, as described in the "Permittivity of Free Space" blue section above, appears in several equations by itself, most notably the Charge-Flux Law (see Rule 188). The reasons for the usage of Coulomb's Constant at all is a matter of antiquated historical decisioning that we have to live with today.

# Isolated System: A system is isolated when charges are not able to enter nor exit the system. The universe, being isolated, has a constant net charge.

#

P. Rule .

Conservation of Charge:

The total electric charge of an isolated system never changes.

qi total = qf total

If the conductors being touched in a conservation of charge-type equation are identical (in all manners other than charge), then the excess charge will be evenly distributed between the two conductors. For example, if there are two conductors, one with a charge of -3 nC and the other with +6 nC, then the final charge of each conductor, once touched, will be 1.5 nC.

The total electric charge of an isolated system never changes.

qi total = qf total

If the conductors being touched in a conservation of charge-type equation are identical (in all manners other than charge), then the excess charge will be evenly distributed between the two conductors. For example, if there are two conductors, one with a charge of -3 nC and the other with +6 nC, then the final charge of each conductor, once touched, will be 1.5 nC.

# Electricity: The flow of electrons through a conductor.

# Conductor: Something that can conduct electricity, like a wire. On the outside of a wire, there is rubber or plastic that serves as an insulator/nonconductor: something that doesn't conduct electricity very well or at all.

# Semiconductor: A material that holds both qualities of a conductor and insulator and can be tailored to be a better conductor or insulator. Depending on electrical signals, it can be conducting or insulating. Examples: Silicon, Germanium.

# Superconductor: An idealized perfect conductor, allowing charge to move without any hindrance.

#

P. Rule .

GROUND.

All excess charges can quickly be diffused through the usage of a Ground. A Ground is any sort of release point (if excess negative) or gain point (if excess positive) for the excess charges of a system: an ideal ground is an infinite well (see VII.VI) of charge carriers - such a requirement is effectively met by the Earth.

An Earth Ground is created when a circuit has a physical connection to the earth, in order to sink (lose) or source (obtain) electrons through the earth itself. The Earth has a practically infinite number of electrons that can be used to balance out a circuit/system, pulling from or giving to it. Relative to very small charged systems, the human skin could serve as a ground as well.

The end result of a ground is an electrically neutral system.

In electrical engineering, all circuits require a Ground to function - it is often referred to as "GND", and has its own symbol for use in diagrams (see E.E. Rule [[[). In many electrical situations, without the availability of a physical connection to the Earth, a "Floating Ground" can be used, which simply serves as a type of '0V reference line' (see def. of Voltage) that acts as a return path for current back to the negative side of the power supply.

All excess charges can quickly be diffused through the usage of a Ground. A Ground is any sort of release point (if excess negative) or gain point (if excess positive) for the excess charges of a system: an ideal ground is an infinite well (see VII.VI) of charge carriers - such a requirement is effectively met by the Earth.

An Earth Ground is created when a circuit has a physical connection to the earth, in order to sink (lose) or source (obtain) electrons through the earth itself. The Earth has a practically infinite number of electrons that can be used to balance out a circuit/system, pulling from or giving to it. Relative to very small charged systems, the human skin could serve as a ground as well.

The end result of a ground is an electrically neutral system.

In electrical engineering, all circuits require a Ground to function - it is often referred to as "GND", and has its own symbol for use in diagrams (see E.E. Rule [[[). In many electrical situations, without the availability of a physical connection to the Earth, a "Floating Ground" can be used, which simply serves as a type of '0V reference line' (see def. of Voltage) that acts as a return path for current back to the negative side of the power supply.

#

P. Rule .

There are two distinct categories, processes under which charge is transferred. Specific means of transfer, like charging by friction (rubbing) fall under these wider processes. These processes are Conduction, and Induction.

Conduction:

This is the transfer of charge in which current flows because of the electric field. There are only two requisites for an object to be charged by conduction, through another object:

1. The objects have to touch.

2. The objects must, after touching, have the same sign of net charge.

Induction:

This is the transfer of charge in which a changing magnetic field generates an electromotive force (see Rule [[[), resulting in an induced charge. It is not important to fully understand what an "electromotive force" is right now, just that it is the electric force that drives current through a circuit.

There are only two requisites for an object to be charged by conduction, and they are the eact opposite of conduction:

1. The objects do not touch.

2. The objects must finish with opposite signs of net charge.

Conduction:

This is the transfer of charge in which current flows because of the electric field. There are only two requisites for an object to be charged by conduction, through another object:

1. The objects have to touch.

2. The objects must, after touching, have the same sign of net charge.

Induction:

This is the transfer of charge in which a changing magnetic field generates an electromotive force (see Rule [[[), resulting in an induced charge. It is not important to fully understand what an "electromotive force" is right now, just that it is the electric force that drives current through a circuit.

There are only two requisites for an object to be charged by conduction, and they are the eact opposite of conduction:

1. The objects do not touch.

2. The objects must finish with opposite signs of net charge.

#

P. Rule .

Polarization:

Polarization is the process through which the charges within objects (and thus their associated particles) align themselves in such a way that there becomes a net attractive force, as a result of attraction & repulsion from an object with excess charge.

Polarization doesn't change the net charge of the object, but rather has to do with how charges rearrange themselves within the object.

The process itself is simple: When an object with an excess charge approaches a neutral object, the like charges will repel and the opposite charges will attract (the electrons being the sole moving particles, moving either in front of or behind the protons). Since the opposite charges will be closer to the charges of the object than the like charges, by the Law of Electric Force, there will be a net attractive electric force, since the opposite charges have a smaller 'r' value than the like charges.

This is the reason that balloons stick to walls once they have an excess negative charge. The wall, as an insulator without free electrons, cannot "attract" the charge of the balloon. Instead, the charges in the wall rearrange themselves and end up with that net attractive force.

Electric force due to polarization is small - objects with small masses, like balloons and aluminum cans, can be held in place and rolled respectively using only a small electric force.

Electric force caused by the polarization of a conductor is typically larger than a polarized insulator. This is because electrons in insulators are bound in their atoms, while electrons in conductors are able to move to the opposite side of the object.

For information as to how polarization can be used to the advantage of a capacitor (Section XVI), see Rule 216.

Polarization is the process through which the charges within objects (and thus their associated particles) align themselves in such a way that there becomes a net attractive force, as a result of attraction & repulsion from an object with excess charge.

Polarization doesn't change the net charge of the object, but rather has to do with how charges rearrange themselves within the object.

The process itself is simple: When an object with an excess charge approaches a neutral object, the like charges will repel and the opposite charges will attract (the electrons being the sole moving particles, moving either in front of or behind the protons). Since the opposite charges will be closer to the charges of the object than the like charges, by the Law of Electric Force, there will be a net attractive electric force, since the opposite charges have a smaller 'r' value than the like charges.

This is the reason that balloons stick to walls once they have an excess negative charge. The wall, as an insulator without free electrons, cannot "attract" the charge of the balloon. Instead, the charges in the wall rearrange themselves and end up with that net attractive force.

Electric force due to polarization is small - objects with small masses, like balloons and aluminum cans, can be held in place and rolled respectively using only a small electric force.

Electric force caused by the polarization of a conductor is typically larger than a polarized insulator. This is because electrons in insulators are bound in their atoms, while electrons in conductors are able to move to the opposite side of the object.

For information as to how polarization can be used to the advantage of a capacitor (Section XVI), see Rule 216.

#

P. Rule .

Placement of Charge within Conductors & Nonconductors:

The nature & positioning of the charge within the thickness of an object (like a shell or thick cylinder) differs depending on whether the material of the object is a conductor or insulator.

Conductive objects (enclosed shapes) spread out all excess charge (read: electrons) over their external surface. This is because the conduction electrons of the conductor (see Rule 162) and the excess charge electrons will repel from one another, causing the excess charge electrons to spread over and distribute across the farthest possible surface.

If the object is symmetrically shaped, like a sphere, this distribution will be uniform. Otherwise, if the object is irregularly shaped, then surface charge density will vary and have specific maximums - see Rule 196 for a complete description.

!!!NOTE!!!: Unless the conductor is circular (spherical or cylindrical), the charge will not distribute itself uniformly. This is a matter of symmetricality, an attribute that leads circular objects (shell or solid) to naturally become uniformly distributed in charge, but not any other shape. This is not to say that a question will not simply say "assume a uniform charge density" for some ridiculous, noncircular shape, violating the laws of physics for the sake of examining the physicist. In such a case, you would do as told and use the given information appropriately. The surface charge density σ (charge per unit area) varies over the surface of any noncircular conductor. The electric field (see Section XIII) immediately outside of the surface of the noncircular shape can be determined quite easily however, as described in Rule 197.

This concentration of charge on the external surface is the same for both positive and negative excess charge. If there is an excess positive charge (imagine the conduction electrons have been removed), then the positive charge will then spread uniformly across the surface. In other words, the "absence of electrons" will be uniformly distributed.

In the state of uniform charge distribution, the conductor will be in a state of electrostatic equilibrium - see Rule 194 for a complete explanation involving Electric Fields.

Nonconductive/Insulating objects (enclosed shapes), which do not allow free movement of charge, bind electrons to their atoms and thus do not move to redistribute excess charge. When an excess charge is added, there are conduction electrons that would even allow for the charge to be moved, and so the excess charge will simply remain wherever it is placed.

Thus, the excess charge can be uniformly distributed if that is the state in which it is added, and questions oftentime instruct the physicist to assume such a condition. However, if the charge is concentrated in a particular region, it will not naturally redistribute itself as it would in a conductor.

For a continuation of this Rule, with respect to how the conductor/nonconductor dispersal of charge affects electric field distribution, see Rule 194.

The nature & positioning of the charge within the thickness of an object (like a shell or thick cylinder) differs depending on whether the material of the object is a conductor or insulator.

Conductive objects (enclosed shapes) spread out all excess charge (read: electrons) over their external surface. This is because the conduction electrons of the conductor (see Rule 162) and the excess charge electrons will repel from one another, causing the excess charge electrons to spread over and distribute across the farthest possible surface.

If the object is symmetrically shaped, like a sphere, this distribution will be uniform. Otherwise, if the object is irregularly shaped, then surface charge density will vary and have specific maximums - see Rule 196 for a complete description.

!!!NOTE!!!: Unless the conductor is circular (spherical or cylindrical), the charge will not distribute itself uniformly. This is a matter of symmetricality, an attribute that leads circular objects (shell or solid) to naturally become uniformly distributed in charge, but not any other shape. This is not to say that a question will not simply say "assume a uniform charge density" for some ridiculous, noncircular shape, violating the laws of physics for the sake of examining the physicist. In such a case, you would do as told and use the given information appropriately. The surface charge density σ (charge per unit area) varies over the surface of any noncircular conductor. The electric field (see Section XIII) immediately outside of the surface of the noncircular shape can be determined quite easily however, as described in Rule 197.

This concentration of charge on the external surface is the same for both positive and negative excess charge. If there is an excess positive charge (imagine the conduction electrons have been removed), then the positive charge will then spread uniformly across the surface. In other words, the "absence of electrons" will be uniformly distributed.

In the state of uniform charge distribution, the conductor will be in a state of electrostatic equilibrium - see Rule 194 for a complete explanation involving Electric Fields.

Nonconductive/Insulating objects (enclosed shapes), which do not allow free movement of charge, bind electrons to their atoms and thus do not move to redistribute excess charge. When an excess charge is added, there are conduction electrons that would even allow for the charge to be moved, and so the excess charge will simply remain wherever it is placed.

Thus, the excess charge can be uniformly distributed if that is the state in which it is added, and questions oftentime instruct the physicist to assume such a condition. However, if the charge is concentrated in a particular region, it will not naturally redistribute itself as it would in a conductor.

For a continuation of this Rule, with respect to how the conductor/nonconductor dispersal of charge affects electric field distribution, see Rule 194.

#

P. Rule .

Shell Theorems of Electric Force:

Shells, spherical or cylindrical entities of a specified thickness and a hollow interior (like a ring rotated 180° along the x-axis, with the thickness being ≥0), retain the same importance they had in Mechanics for Electromagnetism.

Akin to the Shell Theorem for Internal Gravitation (see Rule 149), there are TWO Shell Theorems for Electric Fields - yet another similarity between electric force and gravitational force (see Rule 163 for the first). They are relatively straightforward, but are only applicable under the specified conditions.

These theorems literally do not work for any shape other than a shell/sphere - there is a particular symmetry with those specific shapes that allow these theorems to be used. They are not true for just any irregular, wack shape.

Fundamental to the understanding of these theorems is the nature of charge distribution on shells, which itself depends on whether the shell is conductive or not. See Rule 170 for a full, generalized treatment of these principles. Nonconductive shells are not in a state of electrostatic equilibrium (see Rule 194), unlike Conductive shells.

Shells, spherical or cylindrical entities of a specified thickness and a hollow interior (like a ring rotated 180° along the x-axis, with the thickness being ≥0), retain the same importance they had in Mechanics for Electromagnetism.

Akin to the Shell Theorem for Internal Gravitation (see Rule 149), there are TWO Shell Theorems for Electric Fields - yet another similarity between electric force and gravitational force (see Rule 163 for the first). They are relatively straightforward, but are only applicable under the specified conditions.

These theorems literally do not work for any shape other than a shell/sphere - there is a particular symmetry with those specific shapes that allow these theorems to be used. They are not true for just any irregular, wack shape.

Fundamental to the understanding of these theorems is the nature of charge distribution on shells, which itself depends on whether the shell is conductive or not. See Rule 170 for a full, generalized treatment of these principles. Nonconductive shells are not in a state of electrostatic equilibrium (see Rule 194), unlike Conductive shells.

- A charged particle outside of a shell with charge uniformly distributed on its surface (e.g., a conductor) is attracted or repelled as if the shell’s charge were concentrated as a particle at its center. This is assuming the charge on the shell is much greater than the charge of the particle, thus not interfering with the distribution of charge on the shell (an issue detailed in Rule 170).

- A charged particle inside a shell with charge uniformly distributed on its surface (e.g., any conductor, and any nonconstructor created in such a way) will have no net force acting on it due to the shell.

XIII. Electric Fields.

XIII.I Introduction to Fields.

If the test charge is positive, then it will be in the same direction as the electric field, and if it is negative, then it will be in the opposite direction of the electric field. By convention, positive test charges are used to define electric fields.

#

P. Rule .

Electric Field: VECTOR.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs.

Equation:

E = (Fe / q)

E = The magnitude of the electric field at a particular point.

Fe = The electric force being felt by the charge at the particular point being measured.

q = The magnitude of the charge/charged particle of the particular point being measured.

Definition: An Electric Field is a field in space surrounding a charged object, in which the object's electric force has strength.

Electric fields have their direction expressed in the form of lines, the nature of which is elucidated in Rule 174. Naturally (meaning without the interference of another electric field), these lines, which originate at every point of the object's surface, will be perpendicular to the object and will point radially outward or inward (depending on the charge sign) forever without bending - the electric field of a point charge, for example, will shoot off in every direction in such a way. The direction and lines themselves, however, can be influenced as a result of the Law of Charges and can bend accordingly - see Rule 174.

Technically, the given equation dictates that the electric field is the "amount of electric force per charge at a point in space", the ratio between the electric force of the charge and the magnitude of the charge itself. All charge creates an electric field in relation to its electric force.

The reason an exact magnitude value can be determined for an electric field (an inherently emanating and changing entity), as is done in the given equation, is because the magnitude being found is that of the strength of electric field at a particular point, denoted by the electric force experienced by the charge placed at that point.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs.

Equation:

E = (Fe / q)

E = The magnitude of the electric field at a particular point.

Fe = The electric force being felt by the charge at the particular point being measured.

q = The magnitude of the charge/charged particle of the particular point being measured.

Definition: An Electric Field is a field in space surrounding a charged object, in which the object's electric force has strength.

Electric fields have their direction expressed in the form of lines, the nature of which is elucidated in Rule 174. Naturally (meaning without the interference of another electric field), these lines, which originate at every point of the object's surface, will be perpendicular to the object and will point radially outward or inward (depending on the charge sign) forever without bending - the electric field of a point charge, for example, will shoot off in every direction in such a way. The direction and lines themselves, however, can be influenced as a result of the Law of Charges and can bend accordingly - see Rule 174.

Technically, the given equation dictates that the electric field is the "amount of electric force per charge at a point in space", the ratio between the electric force of the charge and the magnitude of the charge itself. All charge creates an electric field in relation to its electric force.

The reason an exact magnitude value can be determined for an electric field (an inherently emanating and changing entity), as is done in the given equation, is because the magnitude being found is that of the strength of electric field at a particular point, denoted by the electric force experienced by the charge placed at that point.

# Uniform Electric Field: An electric field that has the same magnitude and direction at every point within the field - think of the electric field created by an infinitely long pole. These electric fields, of course, are overtly idealized.

#

P. Rule .

The magnitude of the electric field will decrease as the test charge gets farther from the point charge, as a result of the Law of Electric Force (since the denominator distance value increases and all). The electric field surrounding (and caused by) a point charge is constant at a constant radius from the point charge.

The entire Law of Electric Force equation can be substituted into the Electric Field equation, enabling one to simplify things considerably if the circumstances allow.

The entire Law of Electric Force equation can be substituted into the Electric Field equation, enabling one to simplify things considerably if the circumstances allow.

#

P. Rule .

Electric Field Lines:

1. The lines of attraction in an electric field always point away from the positive charge (origination) and toward the negative charge (termination). Thus, the lines always point in the direction in which the test charge would experience an electric force.

2. The # of electric field lines per unit area is proportional to the electric field strength. Therefore, a higher density of electric field lines means a higher electric field strength.

3. Electric field lines always start perpendicularly to the surface of the charge, and start on a positive charge and end on a negative charge (unless there is more of one charge, in which case some lines would start/end infinitely far away).

4. Electric field lines never cross.

Use the test charge (a positive entity - see the definition) as the sample particle, for the sake of illustrating this point.

When the test charge (standardized as positive) is placed in the field of a positive point charge, the test charge will be repelled from the point charge. Electric force projects radially outward from the positive point charge, decreasing in magnitude as distance increases.

On the flip side, if the point charge is negative, then the test charge will be attracted toward the point charge. All of the arrows will point radially inward toward the negative point charge.

1. The lines of attraction in an electric field always point away from the positive charge (origination) and toward the negative charge (termination). Thus, the lines always point in the direction in which the test charge would experience an electric force.

2. The # of electric field lines per unit area is proportional to the electric field strength. Therefore, a higher density of electric field lines means a higher electric field strength.

3. Electric field lines always start perpendicularly to the surface of the charge, and start on a positive charge and end on a negative charge (unless there is more of one charge, in which case some lines would start/end infinitely far away).

4. Electric field lines never cross.

Use the test charge (a positive entity - see the definition) as the sample particle, for the sake of illustrating this point.

When the test charge (standardized as positive) is placed in the field of a positive point charge, the test charge will be repelled from the point charge. Electric force projects radially outward from the positive point charge, decreasing in magnitude as distance increases.

On the flip side, if the point charge is negative, then the test charge will be attracted toward the point charge. All of the arrows will point radially inward toward the negative point charge.

XIII.II Continuous Charge Distributions.

λ = (Q / L)

λ = (Lambda) The direction and magnitude of the given expression, defined in Coulombs per Meter (C / m).

Q = The charge of the object.

L = The length of the object - this form of density is best applied to charge along a flat line.

Treat λ as a constant when taking the derivative. Note, however, that the given equation can be transmuted into a derivative form: λ = (dQ / dL). This is because the ratio remains the same: total charge divided by total length is equal to the infinitesimally small individual charge over the length thereof.

# Surface Charge Density:

σ = (Q / A)

σ = (Sigma) The direction and magnitude of the given expression, defined in Coulombs per Meter Squared (C / m²).

Q = The charge of the object.

A = The total area of the object.

Treat σ as a constant when taking the derivative. Note, however, that the given equation can be transmuted into a derivative form: σ = (dQ / dA). This is because the ratio remains the same: total charge divided by total area is equal to the infinitesimally small individual charge over the area thereof.

# Volumetric Charge Density:

ρ = (Q / V)

ρ = (Rho) The direction and magnitude of the given expression, defined in Coulombs per Meter Cubed (C / m³).

Q = The charge of the object.

V = The total volume of the object.

Treat ρ as a constant when taking the derivative. Note, however, that the given equation can be transmuted into a derivative form: ρ = (dQ / dV). This is because the ratio remains the same: total charge divided by total volume is equal to the infinitesimally small individual charge over the volume thereof.

#

P. Rule .

Electric Field of a Continuous Charge Distribution (CCD): VECTOR.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. It is a type of electric field.

Equation:

$$E_{CCD} = k \int \frac{dq}{r^2} \hat{r}$$

ECCD = The electric field that exists around a continuous charge distribution, calculated at point r in space.

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

dq = The infinitesimally small point charges, of which there is an infinite number of. This value can be substituted for any of the equivalent charge density derivatives (see Linear, Surface, and Volumetric), pursuant to the nature of a particular problem.

r = The distance between the infinitesimal charge dq and the point where the electric field is being calculated. Unlike the Law of Electric Force, this r is a function that varies depending on the charge, since there is technically an infinite number of charges (dq).

r̂ = The unit vector pointing from dq (whichever charge) toward the test charge - this is most applicable post-integral, when you can have a test charge to calculate the strength of the electric field with respect to. The direction points radially outward for positive dq, and inward for negative dq.

Definition: A Continuous Charge Distribution (CCD) is a simple concept that elaborates the simple 'point' model of charges into one that uses calculus to account for more chargetype possibilities, furthering the infinite journey into human knowledge.

A 'continuous charge distribution' is simply a charge that isn't a point charge; e.g., a charge with a shape and an electric charge continuously distributed throughout the object.

The electric field that exists around a continuous charge distribution can be determined through a rethinking of the standard Electric Field-Law of Electric Force combined equation (see Rule 172) using Calculus. Since the charged object is made up of an infinite number of infinitesimally small point charges ('dq' representing them individually), the therefore infinite number of electric fields can be calculated using an integral.

There are very specific use cases for this integral: it is not applicable everywhere. See Rule 176 for a detailed treatise on this cases and their exceptions. The limits of integration of the integral are specific to each problem and can be determined through ingenuity and through the power of the indomitable human spirit.

That pesky 'dq' thing can be switched out by taking the derivative of any of the charge densities (see linear, surface, and volumetric), depending on what one is looking for.

The Electric Potential created by a CCD has a near identical equation to its electric field, described in Rule 206.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. It is a type of electric field.

Equation:

$$E_{CCD} = k \int \frac{dq}{r^2} \hat{r}$$

ECCD = The electric field that exists around a continuous charge distribution, calculated at point r in space.

k = The Coulomb constant, equal to 8.99 × 10⁹ (N × m²) / (C²).

dq = The infinitesimally small point charges, of which there is an infinite number of. This value can be substituted for any of the equivalent charge density derivatives (see Linear, Surface, and Volumetric), pursuant to the nature of a particular problem.

r = The distance between the infinitesimal charge dq and the point where the electric field is being calculated. Unlike the Law of Electric Force, this r is a function that varies depending on the charge, since there is technically an infinite number of charges (dq).

r̂ = The unit vector pointing from dq (whichever charge) toward the test charge - this is most applicable post-integral, when you can have a test charge to calculate the strength of the electric field with respect to. The direction points radially outward for positive dq, and inward for negative dq.

Definition: A Continuous Charge Distribution (CCD) is a simple concept that elaborates the simple 'point' model of charges into one that uses calculus to account for more chargetype possibilities, furthering the infinite journey into human knowledge.

A 'continuous charge distribution' is simply a charge that isn't a point charge; e.g., a charge with a shape and an electric charge continuously distributed throughout the object.

The electric field that exists around a continuous charge distribution can be determined through a rethinking of the standard Electric Field-Law of Electric Force combined equation (see Rule 172) using Calculus. Since the charged object is made up of an infinite number of infinitesimally small point charges ('dq' representing them individually), the therefore infinite number of electric fields can be calculated using an integral.

There are very specific use cases for this integral: it is not applicable everywhere. See Rule 176 for a detailed treatise on this cases and their exceptions. The limits of integration of the integral are specific to each problem and can be determined through ingenuity and through the power of the indomitable human spirit.

That pesky 'dq' thing can be switched out by taking the derivative of any of the charge densities (see linear, surface, and volumetric), depending on what one is looking for.

The Electric Potential created by a CCD has a near identical equation to its electric field, described in Rule 206.

#

P. Rule .

The integral equation for CCDs (continuous charge distributions, see Rule 175) is only applicable when every infinitesimal charge has its electric field pointing in the same direction when it is pointing toward the test point. For example: when the CCD is a flat line, and the test charge is on its same axis.

There are some workarounds in which the above stipulation is technically still respected, allowing the integral to still be used even for shapes like rings. This is when all components in all other directions cancel out, leaving only the components in a specific direction. For example, in a uniformly charged ring, the horizontal components of the field from symmetric charge elements cancel, leaving only the vertical (axial) component.

When all fails, and the direction of the electric at test charge P is simply not the same for every charge dq on the ring, then take the derivative of both sides of the equation (giving dE) and try to see if any components cancel eachother out anywhere - in order to find the components, use the direction of the electric field from or toward the test charge (remember: the direction points radially outward for positive dq, and inward for negative dq), and imagine that beyond the test charge or dq, wherever the direction points, the direction line continues - this extended line segment represents dE, which can then be broken into components (which will hopefully cancel out in one direction). If there are equal negative and positive dq's in a particular direction, then it cancels out. Ideally, the direction that doesn't cancel out should only a single sign no matter the direction/origin of the dq.

Generally, the dq electric field values in a particular direction 'cancelling out' is the result of a symmetry created by the placement of the point charge. For example, a point charge placed somewhere along the axis of the center of the ring.

If one has succeeded in cancelling out, then they would be able to proceed with all the necessary moving of sines or cosines (resultant from the components) and the general transfiguration of terms dependent on the characteristics of the problem itself. After one has been able to simplfy and reduce everything into only one real variable on one side (every other symbol just being a constant), then both sides can be integrated, creating a problem-specific version of the hyper-generalized CCD integral equation (see Rule 175).

All this component business requires that there be some reference position, a known x-axis and y-axis positioning in relation to the given CCD and point charge that can be used to derive the components from.

There are some workarounds in which the above stipulation is technically still respected, allowing the integral to still be used even for shapes like rings. This is when all components in all other directions cancel out, leaving only the components in a specific direction. For example, in a uniformly charged ring, the horizontal components of the field from symmetric charge elements cancel, leaving only the vertical (axial) component.

When all fails, and the direction of the electric at test charge P is simply not the same for every charge dq on the ring, then take the derivative of both sides of the equation (giving dE) and try to see if any components cancel eachother out anywhere - in order to find the components, use the direction of the electric field from or toward the test charge (remember: the direction points radially outward for positive dq, and inward for negative dq), and imagine that beyond the test charge or dq, wherever the direction points, the direction line continues - this extended line segment represents dE, which can then be broken into components (which will hopefully cancel out in one direction). If there are equal negative and positive dq's in a particular direction, then it cancels out. Ideally, the direction that doesn't cancel out should only a single sign no matter the direction/origin of the dq.

Generally, the dq electric field values in a particular direction 'cancelling out' is the result of a symmetry created by the placement of the point charge. For example, a point charge placed somewhere along the axis of the center of the ring.

If one has succeeded in cancelling out, then they would be able to proceed with all the necessary moving of sines or cosines (resultant from the components) and the general transfiguration of terms dependent on the characteristics of the problem itself. After one has been able to simplfy and reduce everything into only one real variable on one side (every other symbol just being a constant), then both sides can be integrated, creating a problem-specific version of the hyper-generalized CCD integral equation (see Rule 175).

All this component business requires that there be some reference position, a known x-axis and y-axis positioning in relation to the given CCD and point charge that can be used to derive the components from.

#

P. Rule .

Note that the farther you get from a finite continuous charge distribution, the more the electric field caused by the CCD matches the electric field caused by a point charge (as in, the simplified Law of Electric Force + Electric Force equation from way back when (see Rule 173)). Of course, this requires the distance between the test charge and the CCD to be much much greater than the internal distance with the CCD itself.

#

P. Rule .

Always be aware of what constants/variables are much much greater than others. In end game integrals, such as in CCD-type problems (see Rule 176), this can totally simplify whole entire parts of your equation by just thinking of the lesser variable as zero (where it is left alone and not acting as a coefficient). Of course, this mandates the usage of the approximation symbol (≈) for your answer.

#

P. Rule .

You can never assume that the equation for the electric field of a shape, whether 2d or 3d, will be the same if the shape is a conductor or a nonconductor. The world is not such a simple, idealistic place, even in what is essentially toy model physics (classical electromagnetism).

The key factor in determining whether the electric field equation for a shape is the same or differing between conductors and nonconductors, is how the charge distributes within the shape.

The following characteristics are indicative of identical equations between the electric field equations of a conductor and nonconductor shape:

The following characteristics are indicative of differing equations between the electric field equations of a conductor and nonconductor shape:

The key factor in determining whether the electric field equation for a shape is the same or differing between conductors and nonconductors, is how the charge distributes within the shape.

The following characteristics are indicative of identical equations between the electric field equations of a conductor and nonconductor shape:

- Infinite Reach: If the shape is infinite (like infinite planes or cylinders), then both conductors and nonconductors produce the same electric field at points sufficiently far from the charge distribution. Example: Infinite planes as explained in Rule 180.

- Symmetric Charge Distributions: There are cases in which some form of symmetry causes the charge distribution to remain unchanged between the conductor and nonconductor.

For example: an infinite line of charge with uniform charge density λ produced the same radial field for both conductors and nonconductors, since, being a line, the charge is "on the surface" regardless of the conductivity of the shape (in terms of how the charge being on the surface is an important distinction between conductors and nonconductors and alters the calculation of their electric fields - see Rule 170), and is emanating outward in the same fashion. - External Field Only: If only the electric field outside of an enclosed shape is being considered, then IF SYMMETRY DICTATES A FIXED CHARGE DISTRIBUTION (like shells and spheres and cylinders and whatnot, not just any wack enclosed shape), then the equation for that electrical field in particular will be the same whether the shape material is a conductor or nonconductor. This is more due to the first shell theorem (see Rule 171) than anything.

The following characteristics are indicative of differing equations between the electric field equations of a conductor and nonconductor shape:

- Internal Charge within Enclosed Shapes: As everyone knows, the charge within an enclosed shape for conductors and nonconductors differs as a result of charge placement in the solid part of the shape (like the shell part of a hollow shell) - see Rule 170. Conductors have zero electric field within themselves, and nonconductors do have some.

- Non-Uniform Charge Distribution: Conductors force charge to redistribute, whereas insulators allow charge to remain fixed. For example: a finite conducting "slab" (like a brick) with excess charge will concentrate charge at the edges, while a nonconductor could have uniform volume charge density.

This will cause differing internal and external electric fields, both for the reason outlined in Difference Characteristic #1 (directly above) and for not meeting the symmetricality requirement of Equivalence Characteristic #3 (further above).

#

P. Rule .

Flat Disks & Infinite Planes: VECTORS.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. They are types of electric fields.

Equation:

$$E_{disk} = \frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0} \left( 1 - \frac{z}{\sqrt{z^2 + R^2}} \right)$$ $$E_{plane} = \frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0}$$

Edisk = The magnitude of the electric field produced by a uniformly charged flat disk, calculated at some point z from the central axis of said disk.

Eplane = The magnitude of the electric field of an infinite plane, independent of distance from the plane (interestingly).

σ = Surface charge density. See treatise here.

ε0 = The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

z = The distance (along the central axis) between the point at which the electric field is being measured, and the center of the disk. z ≥ 0.

R = The radius of the disk.

Definition: The Electric Field due to a (flat) uniformly charged disk and due to an infinite sheet are, in fact, closely related, the latter effectively being derived from the former.

The first equation gives the electric field magnitude on the central axis through a flat, circular, uniformly charged disk. The equation is derived in a highly logical and annoying manner, found here (offsite).

If one were to plug in infinity for R, letting the radius rise to infinity while keeping the z value finite, then the equation would simplify to that of the equation for the electric field of an infinite plane, the second given equation. By their very nature, all fields produced by infinite planes will be uniform, and thus will not change with respect to distance. The straight, parallel field lines will neither converge nor diverge from their source (the plane), and as such the field intensity will never change. READ: Electric Field is Uniform when created by a plane.

Note that despite the equation specifically being for disks and circular 2d shapes, the very act of making the radius infinite will create a plane, and thus makes its circular origins irrelevant.

By virtue of the shape being infinite (passing Equivalence Characteristic #1, see Rule 179), the infinite plane equation is true for both conductor and nonconductor infinite planes. Furthermore, know that it is also the equation for the electric field at the surface of a nonconductor, as explained in Rule 197.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. They are types of electric fields.

Equation:

$$E_{disk} = \frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0} \left( 1 - \frac{z}{\sqrt{z^2 + R^2}} \right)$$ $$E_{plane} = \frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0}$$

Edisk = The magnitude of the electric field produced by a uniformly charged flat disk, calculated at some point z from the central axis of said disk.

Eplane = The magnitude of the electric field of an infinite plane, independent of distance from the plane (interestingly).

σ = Surface charge density. See treatise here.

ε0 = The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

z = The distance (along the central axis) between the point at which the electric field is being measured, and the center of the disk. z ≥ 0.

R = The radius of the disk.

Definition: The Electric Field due to a (flat) uniformly charged disk and due to an infinite sheet are, in fact, closely related, the latter effectively being derived from the former.

The first equation gives the electric field magnitude on the central axis through a flat, circular, uniformly charged disk. The equation is derived in a highly logical and annoying manner, found here (offsite).

If one were to plug in infinity for R, letting the radius rise to infinity while keeping the z value finite, then the equation would simplify to that of the equation for the electric field of an infinite plane, the second given equation. By their very nature, all fields produced by infinite planes will be uniform, and thus will not change with respect to distance. The straight, parallel field lines will neither converge nor diverge from their source (the plane), and as such the field intensity will never change. READ: Electric Field is Uniform when created by a plane.

Note that despite the equation specifically being for disks and circular 2d shapes, the very act of making the radius infinite will create a plane, and thus makes its circular origins irrelevant.

By virtue of the shape being infinite (passing Equivalence Characteristic #1, see Rule 179), the infinite plane equation is true for both conductor and nonconductor infinite planes. Furthermore, know that it is also the equation for the electric field at the surface of a nonconductor, as explained in Rule 197.

XIII.III Dipole Moment.

#

P. Rule .

Electric Dipole, Electric Field (along dipole axis): VECTOR.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. It is a type of electric field.

Equation:

Edipole = (1 / 2πε0) × (qd / z³)

Edipole = The electric field produced by a dipole along its axis, calculated with respect to the distance between the test charge and the dipole midpoint.

ε0 = The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

q = The absolute value of the charge of either particle.

d = The distance between the particles.

z = The distance between the test charge (the point at which the electric field is being calculated, which, being somewhere on the dipole axis, will be directly above or below the particles) and the dipole midpoint (d/2). z MUST be >>> to d, for reasons detailed in the proof (see below).

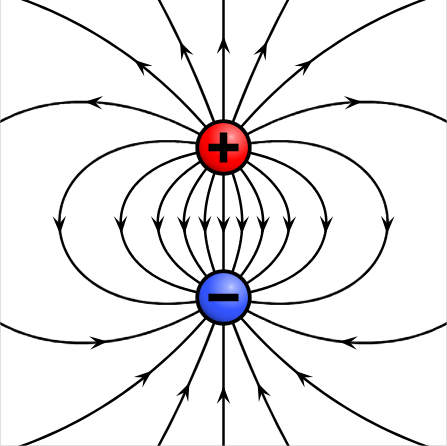

Definition: An Electric Dipole is an arrangement of two particles (point charges) with equal charge magnitudes but opposite signs. The particles are separated by distance d and lie along the dipole axis, an axis of symmetry going through both particles.

A simple graphic of what this entails is seen below:

An example dipole moment, with the dipole axis running straight through the center.

The equation for the electric field produced by a dipole along its axis (and NOWHERE ELSE) is presented above. The electric field created at other points involves much more difficult, graduate-level math (offsite), and thus is dealt with much later in Physics (see Rule [[[).

There is a simple proof of the given equation, done through finding the strength of the net electric field produced by the two particles at an arbitrary point P (the test charge) along the dipole axis. It can be found here (onsite).

The internal force on the electric dipole (Fnet) will equal to zero, since the attractive forces between the particles are equal and opposite in magnitude, forming a Newton's Third Law Force Pair. They will thus be in equilibrium.

The product qd on the right side of the equation is known as the "electric dipole moment", a concept discussed in Rule 183.

The electric potential produced by an electric dipole, which can be easily found for any point (not just axial points), is detailed in Rule 205.

Units: Newtons / Coulombs. It is a type of electric field.

Equation:

Edipole = (1 / 2πε0) × (qd / z³)

Edipole = The electric field produced by a dipole along its axis, calculated with respect to the distance between the test charge and the dipole midpoint.

ε0 = The Permittivity of Free Space, equal to 8.85 × 10⁻¹² (C²) / (N × m²).

q = The absolute value of the charge of either particle.

d = The distance between the particles.

z = The distance between the test charge (the point at which the electric field is being calculated, which, being somewhere on the dipole axis, will be directly above or below the particles) and the dipole midpoint (d/2). z MUST be >>> to d, for reasons detailed in the proof (see below).

Definition: An Electric Dipole is an arrangement of two particles (point charges) with equal charge magnitudes but opposite signs. The particles are separated by distance d and lie along the dipole axis, an axis of symmetry going through both particles.

A simple graphic of what this entails is seen below:

An example dipole moment, with the dipole axis running straight through the center.

The equation for the electric field produced by a dipole along its axis (and NOWHERE ELSE) is presented above. The electric field created at other points involves much more difficult, graduate-level math (offsite), and thus is dealt with much later in Physics (see Rule [[[).

There is a simple proof of the given equation, done through finding the strength of the net electric field produced by the two particles at an arbitrary point P (the test charge) along the dipole axis. It can be found here (onsite).

The internal force on the electric dipole (Fnet) will equal to zero, since the attractive forces between the particles are equal and opposite in magnitude, forming a Newton's Third Law Force Pair. They will thus be in equilibrium.

The product qd on the right side of the equation is known as the "electric dipole moment", a concept discussed in Rule 183.

The electric potential produced by an electric dipole, which can be easily found for any point (not just axial points), is detailed in Rule 205.

#

P. Rule .

Because of the 1/z³ dependence, the field magnitude of an electric dipole decreases more rapidly with distance than the field magnitude of either of the individual charges forming the dipole (which depends on 1/r²). Even beyond that, this is relatively clear when considering how at distant points, the electric fields of the oppositely charged particles will increasingly cancel eachother out.

#

P. Rule .

Electric Dipole Moment:

The 'qd' from the Dipole Electric Field equation (see Rule 181) is known as the Electric Dipole Moment, and can have the value 'p' substituted in for it. It has the unit of the coulomb-meter, of course.

The Dipole Moment is defined as the magnitude of the dipole, purely a matter of charge and distance. This is separate from the magnitude of the electric field of the dipole at a point - that already has its own equation established, see Rule 181. The electric field generated by the dipole is proportional to the dipole moment, though they are always in opposite directions, since the electric field points from the positive charge to the negative charge.

The Electric Dipole Moment is to the Dipole Electric Field equation, what the Discriminant is to the Quadratic Formula (see Math Rule 33), perhaps even to a further degree in which the electric dipole moment can be considered even more important than its forebear.

The direction of p is simply the axis on which the dipole resides, while the sense (see Math Rule [[[) is pointing from the negative toward the positive charge of the dipole.

The 'qd' from the Dipole Electric Field equation (see Rule 181) is known as the Electric Dipole Moment, and can have the value 'p' substituted in for it. It has the unit of the coulomb-meter, of course.

The Dipole Moment is defined as the magnitude of the dipole, purely a matter of charge and distance. This is separate from the magnitude of the electric field of the dipole at a point - that already has its own equation established, see Rule 181. The electric field generated by the dipole is proportional to the dipole moment, though they are always in opposite directions, since the electric field points from the positive charge to the negative charge.

The Electric Dipole Moment is to the Dipole Electric Field equation, what the Discriminant is to the Quadratic Formula (see Math Rule 33), perhaps even to a further degree in which the electric dipole moment can be considered even more important than its forebear.

The direction of p is simply the axis on which the dipole resides, while the sense (see Math Rule [[[) is pointing from the negative toward the positive charge of the dipole.

# Induced Dipole Moments:

Many molecules, such as water, have permanent electric dipole moments. In all isolated atoms and in some types of molecules, the centers of the positive and negative charges coincide and thus have no dipole. These are known as nonpolar molecules.

However, if such an atom or a nonpolar molecule were to be placed in an external electric field, the field would distort the electron orbits and separate the centers of positive and negative charge, effectively creating an electric dipole.

Because the electrons are negatively charged, they tend to be shifted in a direction opposite the field. This shift sets up a dipole moment p (see Rule 183) that points in the direction of the field. This dipole moment is said to be induced by the field, while the atom or molecule is then said to be polarized by the field (that is, it has a positive side and a negative side).

When the field is removed, the induced dipole moment and the polarization disappear.

XIV. Electric Flux.

XIV.I Uniform Flux.

#

P. Rule .

In defining "Electric Flux", the focus of this section, one must understand a fundamental reconsideration of how one views electric fields themselves - if not, the following definitions and descriptions of Electric Flux will seem nonsensical.

First, note that the previous usage of electrical fields treated them like a structured object, a vector field, in which every point in space around it has a magnitude and a direction in relation to the field. In this mindset, an electric field is limited to just being a function that varies with spacial positioning.

The new, super ultra modern rethinking of electric fields, treats them as a measurement of an amount - something that can be summed up, through integration. By saying "the amount of electric field", what this statement is really referring to is the cumulative influence of the electric field across a given area - in relation to electric flux, the cumulative influence of the electric field passing through a surface.

This use of language is jarring at first, but can be quickly accustomed to by the young physicist. Before, electric fields were solely used in the form of a countable noun (like "apples") - now, they can also be used in the form of an uncountable noun (like "knowledge"). Without further ado:

First, note that the previous usage of electrical fields treated them like a structured object, a vector field, in which every point in space around it has a magnitude and a direction in relation to the field. In this mindset, an electric field is limited to just being a function that varies with spacial positioning.

The new, super ultra modern rethinking of electric fields, treats them as a measurement of an amount - something that can be summed up, through integration. By saying "the amount of electric field", what this statement is really referring to is the cumulative influence of the electric field across a given area - in relation to electric flux, the cumulative influence of the electric field passing through a surface.

This use of language is jarring at first, but can be quickly accustomed to by the young physicist. Before, electric fields were solely used in the form of a countable noun (like "apples") - now, they can also be used in the form of an uncountable noun (like "knowledge"). Without further ado:

#

P. Rule .

Uniform Electric Flux: SCALAR.

Units: (Newtons × Meters²) / Coulombs

Equation:

ΦE = E × A × cos(θ)

ΦE = The magnitude of Electric Flux over a Uniform Electric Field (see definition below).

E = The magnitude of a uniform electric field, the amount of which (see Rule 184) is measured over a surface and not just at an individual point in space (though, being uniform, it will have the same strength at any individual point in space). Given how the existing Electric Field equation (see Rule 172) only specifically calculates the magnitude of an electric force at a point, this equation is overly idealized in assuming a uniform electric field (therefore not a point charge or anything similar).

A = The magnitude of the area of the surface through which the uniform electric field is passing. AREA, not VOLUME (explained in def.).

θ = The angle between the directions of the electric field and the direction of the area (area having its direction perpendicular to the plane, and directed outward for closed surfaces). This value, given that all other values in the equation are positive magnitudes, determines whether the flux is positive or negative.

Definition: Electric flux is the measure of the amount of electric field (see Rule 184) which passes through a defined area. The given equation is specifically for uniform electric fields, something that is totally idealized and never really happens in reality.

This equation in particular is the result of a dot product between the electric field and the surface - this is why the result of the equation is a scalar, and why a cosine is used for the theta.

Because this equation is a dot product, that means the two variables are vectors, both with magnitude and direction. Area, the result of a cross product between two vectors (see Math Rule [[[), has a direction normal to the plane of the area, just like how the direction of angular velocity is normal to the plane in which the object is rotating (see Rule 51).

Note that this equation uses AREA, not VOLUME. When the electric field is passing a multi-sided object, the electric flux must be determined for each side of the object and summed thereafter, forming Φtotal.

Generally, using this equation to determine electric flux is optimal when the flux is passing through some sort of closed surface (see Rule 187).

Units: (Newtons × Meters²) / Coulombs

Equation:

ΦE = E × A × cos(θ)

ΦE = The magnitude of Electric Flux over a Uniform Electric Field (see definition below).

E = The magnitude of a uniform electric field, the amount of which (see Rule 184) is measured over a surface and not just at an individual point in space (though, being uniform, it will have the same strength at any individual point in space). Given how the existing Electric Field equation (see Rule 172) only specifically calculates the magnitude of an electric force at a point, this equation is overly idealized in assuming a uniform electric field (therefore not a point charge or anything similar).

A = The magnitude of the area of the surface through which the uniform electric field is passing. AREA, not VOLUME (explained in def.).

θ = The angle between the directions of the electric field and the direction of the area (area having its direction perpendicular to the plane, and directed outward for closed surfaces). This value, given that all other values in the equation are positive magnitudes, determines whether the flux is positive or negative.

Definition: Electric flux is the measure of the amount of electric field (see Rule 184) which passes through a defined area. The given equation is specifically for uniform electric fields, something that is totally idealized and never really happens in reality.

This equation in particular is the result of a dot product between the electric field and the surface - this is why the result of the equation is a scalar, and why a cosine is used for the theta.

Because this equation is a dot product, that means the two variables are vectors, both with magnitude and direction. Area, the result of a cross product between two vectors (see Math Rule [[[), has a direction normal to the plane of the area, just like how the direction of angular velocity is normal to the plane in which the object is rotating (see Rule 51).