These are my complete notes for Circuitry in Electromagnetism.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Circuitry (Electromagnetism)

Table Of Contents

XVIII. Circuitry.

XVIII.I Electric Components & Symbolism.

An electric circuit is generally composed of electrical loops which can include wires, batteries (Rule [[[), resistors (Rule [[[), lightbulbs (Rule [[[), capacitors (Rule [[[), switches (Rule [[[), Ammeters (Rule [[[), and Voltmeters (Rule [[[). A final circuit element, inductors (Rule [[[), is dealt with later on in the summaries ([[[) because it requires knowledge of magnetism and inductance, more advanced subjects.

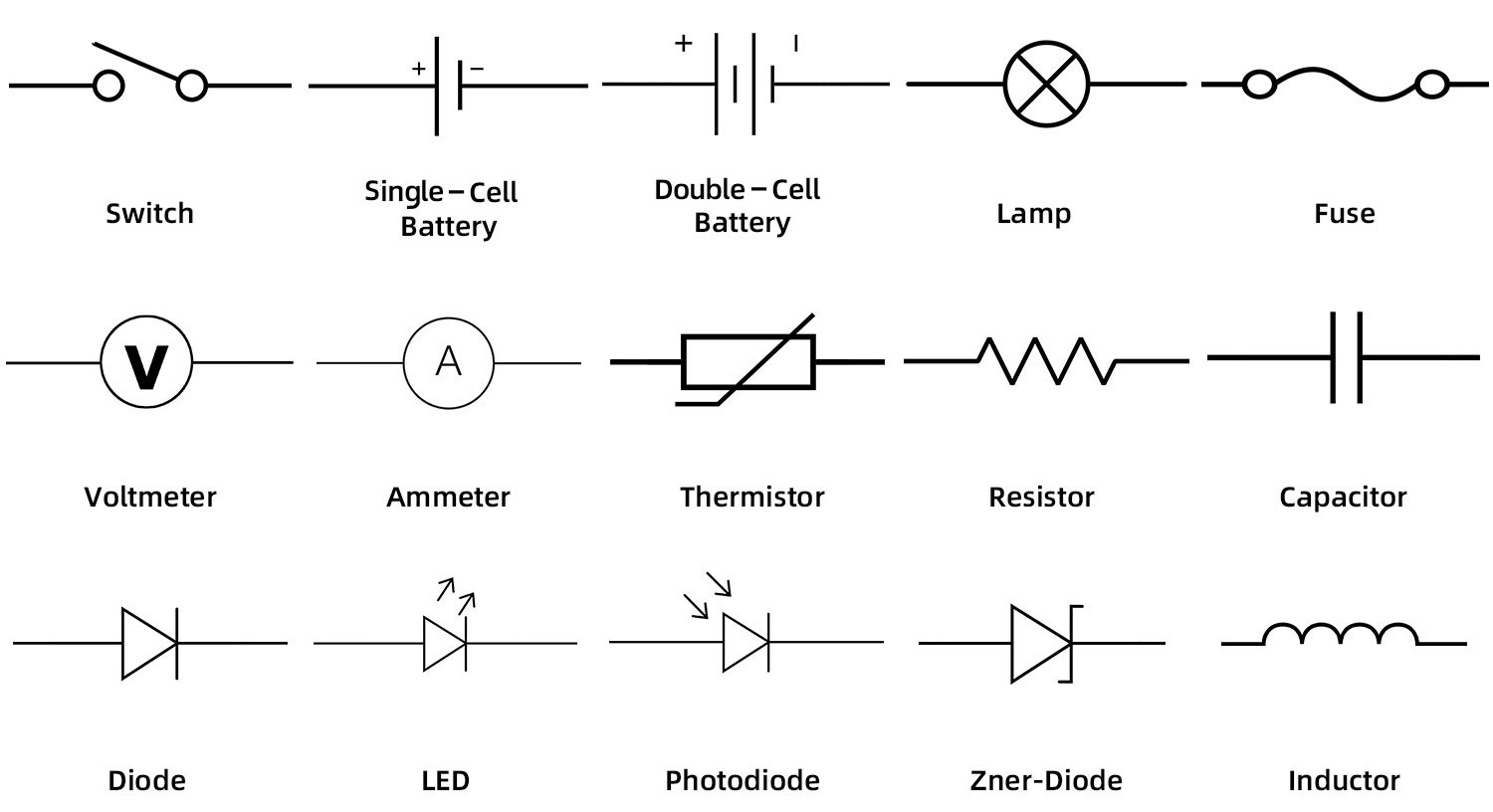

These components are all represented with their own symbols in circuit diagrams. The below illustration displays the most popularly used components in diagrams.

The most commonly used electric component symbols, most explained individually within the Rules of this section. Courtesy of NextPCB.

# Open Circuit: A circuit in which there is no closed loop for electrons to flow, thus producing zero net current.

# Closed Circuit: A circuit in which there is a closed loop that enables electrons to flow, producing a current. While a conductor (like copper) connecting two wires will close a circuit, an insulator (like glass) would not.

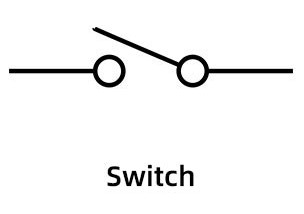

# Switch: An electrical component that only serves to close or open a circuit. When the switch is shut, it closes the circuit, and when it is open, then the circuit is open as well, resulting in all of the aforementioned effects (see above definitions). Switches are represented using the following symbol:

The electric symbol for a switch. Courtesy of NextPCB.

XVIII.II Batteries.

#

P. Rule .

Battery:

Batteries are the source of the electric potential difference between the positive and negative ends of a circuit. It is, thus, inherently the source of the electromotive force (when idealized), described in Rule [[[.

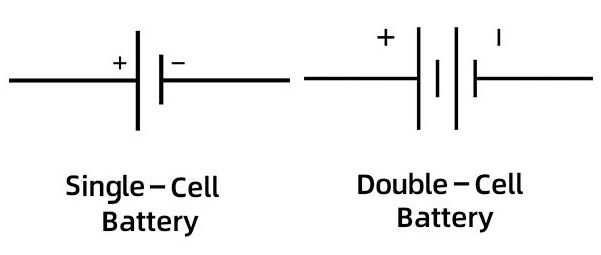

In a circuit diagram, a battery is represented with two plates of differing signs, with the positive and negative sides clearly labeled. When viewing a circuit, it should ALWAYS be followed as having the current start from the positive end (for the reasons originally noted in Rule [[[) and move along the circuit towards the negative end.

The electric symbols for single-cell and double-cell batteries. Courtesy of NextPCB.

The long line of the battery is the positive terminal, while the short line is the negative terminal. Furthermore, when the battery is ideal and has no internal resistance, the electromotive force symbol (see Rule [[[) is placed near the battery on the circuit, since the battery is the starting and ending point of the electric potential difference. For more details as to internal resistance and how one should deal with it, see Rule [[[.

For information as to battery "cells", see Rule [[[+1. See Rule [[[ for relevant information about internal resistance.

Batteries are the source of the electric potential difference between the positive and negative ends of a circuit. It is, thus, inherently the source of the electromotive force (when idealized), described in Rule [[[.

In a circuit diagram, a battery is represented with two plates of differing signs, with the positive and negative sides clearly labeled. When viewing a circuit, it should ALWAYS be followed as having the current start from the positive end (for the reasons originally noted in Rule [[[) and move along the circuit towards the negative end.

The electric symbols for single-cell and double-cell batteries. Courtesy of NextPCB.

The long line of the battery is the positive terminal, while the short line is the negative terminal. Furthermore, when the battery is ideal and has no internal resistance, the electromotive force symbol (see Rule [[[) is placed near the battery on the circuit, since the battery is the starting and ending point of the electric potential difference. For more details as to internal resistance and how one should deal with it, see Rule [[[.

For information as to battery "cells", see Rule [[[+1. See Rule [[[ for relevant information about internal resistance.

#

P. Rule .

Battery Cells:

The electric potential difference supplied by the battery is determined by the number of "cells" within a battery. Each cell produces a fixed amount of electric potential difference, and by adding more, the total electric potential difference of the battery (and thus the circuit) will increase, allowing it to drive a greater level of current. Illustrated above in Rule [[[-1 are the symbols for single-cell and double-cell batteries.

The electric potential difference supplied by the battery is determined by the number of "cells" within a battery. Each cell produces a fixed amount of electric potential difference, and by adding more, the total electric potential difference of the battery (and thus the circuit) will increase, allowing it to drive a greater level of current. Illustrated above in Rule [[[-1 are the symbols for single-cell and double-cell batteries.

#

P. Rule .

Current and Voltage in a Circuit:

Within a circuit, the electric current will always remain constant when the path is undivided. On an individual level, current is constant across each electrical component (whether resistor or capacitor or whatever). The reason for this is explained in Rule [[[understandingheart[[[.

The only times in which the current running through a circuit can differ at two places is when the circuit path is divided - i.e., when the circuit has a junction (a splitting of the wires onto separate paths), with the electrical components along the paths being "parallel". See Rule [[[ for more information regarding this phenomenon. The circuit will always have its paths reconverge by the time the negative terminal is reached, and so the current through both terminals is always the same.

The Electric Potential Difference (Voltage) will, of course, fluctuate as the charge moves from one end of the circuit to the other, as the "difference" will inherently decrease between the two ends of the battery (for example, a "5V" circuit has an electric potential of 5 Volts on the positive terminal and 0 Volts on the negative terminal).

Voltage will only lower, however, as the charge passes through an electrical component, and not while going through a resistance-less wire (see Rule [[[). Thus, the electric potential difference between the farthest extent of the wire connected to the positive terminal and the wire connected to the negative terminal will be the same as that between the terminals (the Terminal Voltage).

Electric potential decreases with every electrical component, decreasing the electric potential difference between the charge position and the negative terminal with each component passed through.

It's important to note that across the different paths of a parallel set (see Rule [[[), Voltage will be the same. This is true regardless of how unbalanced the component distribution is between the paths - regardless of whether there are five components on one path and two components on the other. Thus, for parallel paths, as the Voltage is the same, if the components on the paths are not identical to eachother, then the current will differ between the two paths to compensate for the different resistance (under the VCR Law, Rule [[[), retaining the same Voltage across the paths.

It is standard convention to treat the negative terminal of a battery as a zero-Volt reference point, with the positive terminal having x number of Volts to start with, and by the time it gets to the end of the circuit loop, reaching zero. Of course, a 9V circuit could have 10 V on the positive and 1 V on the negative (since difference is relative), but where not otherwise stated, assume the circuit has the negative terminal set as a 0 V reference point. In [[[kirchhoff's 2nd law - create a little narrative here giving an exact scientific reason for why Voltage must cancel out and whatever[[[

Within a circuit, the electric current will always remain constant when the path is undivided. On an individual level, current is constant across each electrical component (whether resistor or capacitor or whatever). The reason for this is explained in Rule [[[understandingheart[[[.

The only times in which the current running through a circuit can differ at two places is when the circuit path is divided - i.e., when the circuit has a junction (a splitting of the wires onto separate paths), with the electrical components along the paths being "parallel". See Rule [[[ for more information regarding this phenomenon. The circuit will always have its paths reconverge by the time the negative terminal is reached, and so the current through both terminals is always the same.

The Electric Potential Difference (Voltage) will, of course, fluctuate as the charge moves from one end of the circuit to the other, as the "difference" will inherently decrease between the two ends of the battery (for example, a "5V" circuit has an electric potential of 5 Volts on the positive terminal and 0 Volts on the negative terminal).

Voltage will only lower, however, as the charge passes through an electrical component, and not while going through a resistance-less wire (see Rule [[[). Thus, the electric potential difference between the farthest extent of the wire connected to the positive terminal and the wire connected to the negative terminal will be the same as that between the terminals (the Terminal Voltage).

Electric potential decreases with every electrical component, decreasing the electric potential difference between the charge position and the negative terminal with each component passed through.

It's important to note that across the different paths of a parallel set (see Rule [[[), Voltage will be the same. This is true regardless of how unbalanced the component distribution is between the paths - regardless of whether there are five components on one path and two components on the other. Thus, for parallel paths, as the Voltage is the same, if the components on the paths are not identical to eachother, then the current will differ between the two paths to compensate for the different resistance (under the VCR Law, Rule [[[), retaining the same Voltage across the paths.

It is standard convention to treat the negative terminal of a battery as a zero-Volt reference point, with the positive terminal having x number of Volts to start with, and by the time it gets to the end of the circuit loop, reaching zero. Of course, a 9V circuit could have 10 V on the positive and 1 V on the negative (since difference is relative), but where not otherwise stated, assume the circuit has the negative terminal set as a 0 V reference point. In [[[kirchhoff's 2nd law - create a little narrative here giving an exact scientific reason for why Voltage must cancel out and whatever[[[

#

P. Rule .

Upon occasion, a foolish question will ask you to find the Voltage/electric potential difference of a component. In these cases, just mentally rephrase the question to ask for the "Voltage across" the component, which is a more logical phrasing of such a question.

Of course, it is perfectly logical to ask for the current of a component, or the resistance/capacitance of a component, but since Voltage is inherently a difference between two points (the effect of the component on which is being measured), it is more accurate to ask for the Voltage across.

Of course, it is perfectly logical to ask for the current of a component, or the resistance/capacitance of a component, but since Voltage is inherently a difference between two points (the effect of the component on which is being measured), it is more accurate to ask for the Voltage across.

#

P. Rule .

Terminal Voltage: SCALAR.

Units: Volts, e.g. Joules / Coulombs. The symbol for the Volts unit, hilariously, is the same as the symbol for electric potential: V.

Equation:

ΔVt = Ɛ (when in an ideal battery)

∆Vt = Ɛ - (I × r) (when in a non-ideal battery)

ΔVt = Terminal Voltage, the total measured electric potential difference supplied between the terminals of a battery.

Ɛ = Electromotive Force, the maximum possible electric potential difference between the terminals of the battery, only achievable when the battery is ideal without any internal resistance.

I = The current flowing through the non-ideal battery.

r = The internal resistance of a non-ideal battery.

Definition: Terminal Voltage is the total measured electric potential difference supplied between the positive and negative terminals of the battery. Note that this represents the actual, measured value of the potential difference, which, in an ideal battery, would be unimpeded by such things like internal resistance and would reflect the greatest possible electric potential difference between the terminals, known as the electromotive force (see Rule [[[).

The difference between the Terminal Voltage of a non-ideal battery and the ideal electromotive force (see Rule [[[) is the electric potential difference of the internal resistance of the battery, ΔVr. This electric potential difference is then simplified into into its components by the VCR law (Rule [[[), thus creating the non-ideal equation seen above.

For all non-ideal batteries, the Terminal Voltage across the battery will decrease as the current through the battery increases, forming an inverse relationship. As one can figure out after momentary analysis, when there is no current in a non-ideal battery, the Terminal Voltage would equal to that of the electromotive force (as internal resistance would equal to zero).

Units: Volts, e.g. Joules / Coulombs. The symbol for the Volts unit, hilariously, is the same as the symbol for electric potential: V.

Equation:

ΔVt = Ɛ (when in an ideal battery)

∆Vt = Ɛ - (I × r) (when in a non-ideal battery)

ΔVt = Terminal Voltage, the total measured electric potential difference supplied between the terminals of a battery.

Ɛ = Electromotive Force, the maximum possible electric potential difference between the terminals of the battery, only achievable when the battery is ideal without any internal resistance.

I = The current flowing through the non-ideal battery.

r = The internal resistance of a non-ideal battery.

Definition: Terminal Voltage is the total measured electric potential difference supplied between the positive and negative terminals of the battery. Note that this represents the actual, measured value of the potential difference, which, in an ideal battery, would be unimpeded by such things like internal resistance and would reflect the greatest possible electric potential difference between the terminals, known as the electromotive force (see Rule [[[).

The difference between the Terminal Voltage of a non-ideal battery and the ideal electromotive force (see Rule [[[) is the electric potential difference of the internal resistance of the battery, ΔVr. This electric potential difference is then simplified into into its components by the VCR law (Rule [[[), thus creating the non-ideal equation seen above.

For all non-ideal batteries, the Terminal Voltage across the battery will decrease as the current through the battery increases, forming an inverse relationship. As one can figure out after momentary analysis, when there is no current in a non-ideal battery, the Terminal Voltage would equal to that of the electromotive force (as internal resistance would equal to zero).

#

P. Rule .

Electromotive Force (emf):

The maximum possible electric potential difference a battery can provide between its negative and positive terminals is known as the electromotive force, known as "emf" to the commonfolk. Represented using Ɛ.

In all non-ideal batteries, the emf will be greater than the actual electrical potential difference of the circuit (the Terminal Voltage, see definition), since internal resistance will screw with it and ruin the perfection. In all ideal batteries however, terminal velocity is equivalent to electric potential difference.

Importantly, note that electromotive force is not a force. The cabal PURPOSELY named it like that so that you would get confused and include it on your free-body diagram. THIS IS EXACTLY WHAT THEY WANT YOU TO DO. It is only a reference to the max electric potential difference, not a force.

The maximum possible electric potential difference a battery can provide between its negative and positive terminals is known as the electromotive force, known as "emf" to the commonfolk. Represented using Ɛ.

In all non-ideal batteries, the emf will be greater than the actual electrical potential difference of the circuit (the Terminal Voltage, see definition), since internal resistance will screw with it and ruin the perfection. In all ideal batteries however, terminal velocity is equivalent to electric potential difference.

Importantly, note that electromotive force is not a force. The cabal PURPOSELY named it like that so that you would get confused and include it on your free-body diagram. THIS IS EXACTLY WHAT THEY WANT YOU TO DO. It is only a reference to the max electric potential difference, not a force.

#

P. Rule .

Internal Resistance:

Idealized batteries, the most commonly used in Physics, are totally without internal resistance. Batteries with internal resistance are known as "Nonideal batteries", while any circuit that has internal resistance of any kind (whether in a battery or within a wire) is known as a "Nonideal circuit".

When a battery is said to have some sort of "internal resistance", just imagine that there is a resistor immediately following the positive terminal of the battery (with no inbetween wire). If a WIRE is said to have internal resistance, just do the same - fashion a resistor at the very beginner of the wire, and it will have the same effect.

Lowercase r is typically the symbol of internal resistance of a battery. When the internal resistance is nonzero, the electrical current will increase as the Terminal Voltage decreases (as ∆Vt = Ɛ - Iinternal, see Rule [[[-1). Thus, with a nonzero internal resistance the only way to get emf equal to Terminal Voltage is for there to be zero current.

Most problems will deal with ideal batteries, and will otherwise inform you of such unideal attributes like internal resistance.

Idealized batteries, the most commonly used in Physics, are totally without internal resistance. Batteries with internal resistance are known as "Nonideal batteries", while any circuit that has internal resistance of any kind (whether in a battery or within a wire) is known as a "Nonideal circuit".

When a battery is said to have some sort of "internal resistance", just imagine that there is a resistor immediately following the positive terminal of the battery (with no inbetween wire). If a WIRE is said to have internal resistance, just do the same - fashion a resistor at the very beginner of the wire, and it will have the same effect.

Lowercase r is typically the symbol of internal resistance of a battery. When the internal resistance is nonzero, the electrical current will increase as the Terminal Voltage decreases (as ∆Vt = Ɛ - Iinternal, see Rule [[[-1). Thus, with a nonzero internal resistance the only way to get emf equal to Terminal Voltage is for there to be zero current.

Most problems will deal with ideal batteries, and will otherwise inform you of such unideal attributes like internal resistance.

#

P. Rule .

Voltmeter:

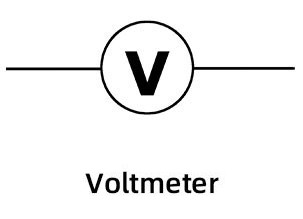

The Voltmeter component is used to measure electric potential difference. It can be strategically placed in the circuit to obtain a value that reflects the Voltage across another component, as a result of Voltage being the same for all components in parallel (see Rule [[[Current and Voltage in a Circuit[[[).

The Voltmeter must be placed in parallel with the electrical component it is measuring the 'Voltage-across' of.

The resistance of a Voltmeter is near infinite (infinite for all intents and purposes), as it must prevent ANY current from moving onto its path (under the current divider law of Rule [[[), as otherwise it will actually provide a parallel path to the component being measured and will decrease the equivalent resistance of the circuit, increasing the current and ruining everything (and interfering with the purely observatory nature of the Voltmeter).

Voltmeters are represented using the following symbol:

The electric symbol for a Voltmeter. Courtesy of NextPCB.

The Voltmeter component is used to measure electric potential difference. It can be strategically placed in the circuit to obtain a value that reflects the Voltage across another component, as a result of Voltage being the same for all components in parallel (see Rule [[[Current and Voltage in a Circuit[[[).

The Voltmeter must be placed in parallel with the electrical component it is measuring the 'Voltage-across' of.

The resistance of a Voltmeter is near infinite (infinite for all intents and purposes), as it must prevent ANY current from moving onto its path (under the current divider law of Rule [[[), as otherwise it will actually provide a parallel path to the component being measured and will decrease the equivalent resistance of the circuit, increasing the current and ruining everything (and interfering with the purely observatory nature of the Voltmeter).

Voltmeters are represented using the following symbol:

The electric symbol for a Voltmeter. Courtesy of NextPCB.

#

P. Rule .

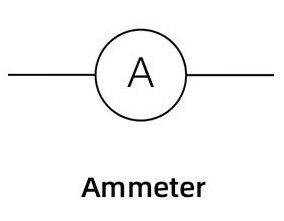

Ammeter:

The Ammeter component is used to measure current, or the number of amperes moving through the circuit at a point. It can be strategically placed in the circuit to obtain a value that reflects the current of another component, as a result of current being the same for all components in series (see Rule [[[Current and Voltage in a Circuit[[[).

The Ammeter must be placed in series with the electrical component it is measuring the 'current-passing-through' of.

The resistance of an Ammeter is near zero (relatively zero for all intents and purposes), as otherwise the equivalent resistance of the circuit will increase and thus the current will decrease, interfering with the purely observatory nature of the Ammeter.

Ammeters are represented using the following symbol:

The electric symbol for an Ammeter. Courtesy of NextPCB.

The Ammeter component is used to measure current, or the number of amperes moving through the circuit at a point. It can be strategically placed in the circuit to obtain a value that reflects the current of another component, as a result of current being the same for all components in series (see Rule [[[Current and Voltage in a Circuit[[[).

The Ammeter must be placed in series with the electrical component it is measuring the 'current-passing-through' of.

The resistance of an Ammeter is near zero (relatively zero for all intents and purposes), as otherwise the equivalent resistance of the circuit will increase and thus the current will decrease, interfering with the purely observatory nature of the Ammeter.

Ammeters are represented using the following symbol:

The electric symbol for an Ammeter. Courtesy of NextPCB.

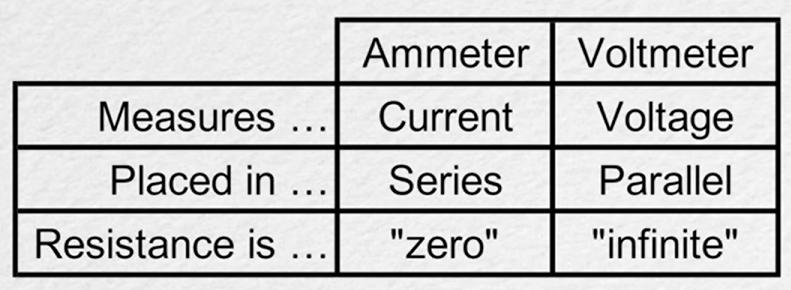

# Ammeter/Voltmeter Memorization Table:

The differences and simplification of the characteristics of the Ammeter and Voltmeter. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

XVIII.III Resistors.

#

P. Rule .

The Understanding At The Heart Of Resistors:

Resistors are the electrical components that have the property of resistance, causing the electric current of the circuit to decrease.

The cabal has cleverly defined resistance as "the ability to resist the flow of electric current". This loses all meaning when one discovers that electrical current is the exact same before and after passing through a resistor. It begs the question: What exactly does a resistor do?

The best way to imagine the effect of the resistor is to realize that it, through the VCR Law, will have a universal effect. When a charge goes through a resistor, it will indeed get slower, and thus will have a lower electrical current. HOWEVER: because all the charges in the circuit are jammed packed together in a line, all of the charges behind those in the resistor will slow down, as they cannot move any faster. As a result, every charge in the circuit will move at the exact same speed when following an individed path (i.e., in series).

In other words, the constant electric current of a circuit is dependent on the total resistance (the equivalent resistance) of the circuit. The greater the strength of a single resistor on one end of the circuit, the lesser the strength of the current throughout the entire. circuit.

All components in series will have the same current, while it will differ between components in parallel (explained below).

It helps to not imagine the charges as individuals detached from the whole, but rather as a sludge, moving together at a constant rate (the current). This sludge, when divided into multiple paths (such as through a junction, which creates parallel components along its individual paths - see Rule [[[), can indeed become slower in its split form along its individual paths (the division of speed of which unto the different paths in fact not being equal, but rather calculated in a specific manner (Rule [[[)), but if the path remains undivided, the sludge will always move at a constant rate.

Resistors are the electrical components that have the property of resistance, causing the electric current of the circuit to decrease.

The cabal has cleverly defined resistance as "the ability to resist the flow of electric current". This loses all meaning when one discovers that electrical current is the exact same before and after passing through a resistor. It begs the question: What exactly does a resistor do?

The best way to imagine the effect of the resistor is to realize that it, through the VCR Law, will have a universal effect. When a charge goes through a resistor, it will indeed get slower, and thus will have a lower electrical current. HOWEVER: because all the charges in the circuit are jammed packed together in a line, all of the charges behind those in the resistor will slow down, as they cannot move any faster. As a result, every charge in the circuit will move at the exact same speed when following an individed path (i.e., in series).

In other words, the constant electric current of a circuit is dependent on the total resistance (the equivalent resistance) of the circuit. The greater the strength of a single resistor on one end of the circuit, the lesser the strength of the current throughout the entire. circuit.

All components in series will have the same current, while it will differ between components in parallel (explained below).

It helps to not imagine the charges as individuals detached from the whole, but rather as a sludge, moving together at a constant rate (the current). This sludge, when divided into multiple paths (such as through a junction, which creates parallel components along its individual paths - see Rule [[[), can indeed become slower in its split form along its individual paths (the division of speed of which unto the different paths in fact not being equal, but rather calculated in a specific manner (Rule [[[)), but if the path remains undivided, the sludge will always move at a constant rate.

#

P. Rule .

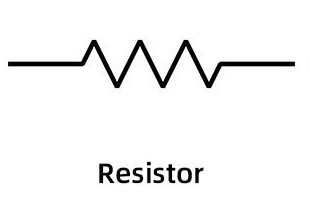

Resistors:

The electrical component that acts as an instrument of resistance to the current. It is THE resistor, nobly standing against a raging electric potential energy.

When a charge passes through a resistor, the electric potential difference will change (as potential energy gets dissipated) while the current will remain constant. Current will remain the same before and after passing through the resistor, conserving charge.

Consider the VCR Law (Rule [[[) on a localized scale, only considering a single resistor. In this scenario, the VCR Law would produce the specs for the state of the charge in the wire immediately following the resistor - this is the data that must be used to discern the effect of any electrical component immediately following the resistor.

Below is the standard depiction of a resistor in circuit diagrams. Occasionally, resistors will be represented as a lame rectangular box instead of a zigzag, the box being small enough that it would not be confused for a junction of wires.

The symbol for the resistor electrical component. Courtesy of NextPCB.

The electrical component that acts as an instrument of resistance to the current. It is THE resistor, nobly standing against a raging electric potential energy.

When a charge passes through a resistor, the electric potential difference will change (as potential energy gets dissipated) while the current will remain constant. Current will remain the same before and after passing through the resistor, conserving charge.

Consider the VCR Law (Rule [[[) on a localized scale, only considering a single resistor. In this scenario, the VCR Law would produce the specs for the state of the charge in the wire immediately following the resistor - this is the data that must be used to discern the effect of any electrical component immediately following the resistor.

Below is the standard depiction of a resistor in circuit diagrams. Occasionally, resistors will be represented as a lame rectangular box instead of a zigzag, the box being small enough that it would not be confused for a junction of wires.

The symbol for the resistor electrical component. Courtesy of NextPCB.

#

P. Rule .

Unless otherwise stated, all wires are considered ideal and have zero resistance.

Under ideal conditions, wires are considered to have zero resistance, and so electrical potential difference will remain the same from one end of the wire to the other, so long as there are no intervening electric components in between. The second there is an electrical component, then there will be a change in electrical potential.

There must always be an electric potential difference between the beginning and end of the circuit, obviously. The ending Electric Potential must be different from the beginning. Otherwise, there would be no current.

Under ideal conditions, wires are considered to have zero resistance, and so electrical potential difference will remain the same from one end of the wire to the other, so long as there are no intervening electric components in between. The second there is an electrical component, then there will be a change in electrical potential.

There must always be an electric potential difference between the beginning and end of the circuit, obviously. The ending Electric Potential must be different from the beginning. Otherwise, there would be no current.

#

P. Rule .

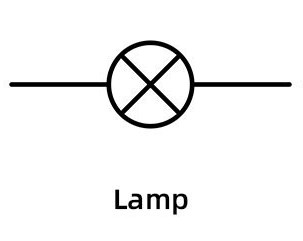

Lightbulbs:

Where there is a symbol for a lightbulb (oftentimes denoted as a "lamp"), treat it as a resistor (Rule [[[).

The brightness of a lightbulb increases with high electric power, and decreases with low electric power, which is obvious considering that brightness is just the dissipation of heat, a euphemism for electric power (see Rule [[[).

The electrical component symbol for a Lamp, also known as a lightbulb. Courtesy of NextPCB.

Where there is a symbol for a lightbulb (oftentimes denoted as a "lamp"), treat it as a resistor (Rule [[[).

The brightness of a lightbulb increases with high electric power, and decreases with low electric power, which is obvious considering that brightness is just the dissipation of heat, a euphemism for electric power (see Rule [[[).

The electrical component symbol for a Lamp, also known as a lightbulb. Courtesy of NextPCB.

#

P. Rule .

Electrical Load:

The part of the circuit which converts electric potential energy into heat, sound, or light, effectively dissipating it into nonconservative energy lost to the system. This part can be the resistor or anything else that has resistance.

The battery can never be a part of electrical load, because it is an electrical power source (the origin of all electric potential difference).

The part of the circuit which converts electric potential energy into heat, sound, or light, effectively dissipating it into nonconservative energy lost to the system. This part can be the resistor or anything else that has resistance.

The battery can never be a part of electrical load, because it is an electrical power source (the origin of all electric potential difference).

#

P. Rule .

Short Circuit:

A circuit which has a very small resistance and thus a very large current is known as a "short circuit". This makes some unstable, since with little resistance and constant Voltage the electric power can be very large and dangerous, as discernable by the equation presented in Rule 232.

A circuit cannot be a circuit if it does not have any resistance. Judging by the VCR Law, a circuit with zero resistance would have infinite current, which is preposterous. All circuits must have some form of resistance, internal/resistor or otherwise.

A circuit which has a very small resistance and thus a very large current is known as a "short circuit". This makes some unstable, since with little resistance and constant Voltage the electric power can be very large and dangerous, as discernable by the equation presented in Rule 232.

A circuit cannot be a circuit if it does not have any resistance. Judging by the VCR Law, a circuit with zero resistance would have infinite current, which is preposterous. All circuits must have some form of resistance, internal/resistor or otherwise.

XVIII.IV Capacitors.

Capacitors store electric potential energy within their electric field, something that gives them unique properties in circuitry. The actual purpose for capacitors in doing so within a circuit, as is taught and is fundamental to Electric Engineering (see E.E. Rule [[[), has to do with Voltage regulation, as current from a battery will come in little bursts rather than in a coherent flow.

However, in freshman Physics, which deals only with the most idealized circuits imaginable, and almost entirely with DC circuits (constant current, see Rule 223), this purpose is all but neglected.

Instead, the more potent and relevant attributes of capacitors, particularly how they play into series and parallel circuits, will be described here somewhat detached from their actual purpose - indeed, this section reflects how to solve problems involving capacitors and their application in Physics rather than anything geared toward actual engineering.

Unless told otherwise (and as previously stated in Rule [[[), every circuit and application of current & Voltage should be assumed to be in DC current (see Rule [[[), with current constant as it moves from the battery.

XVIII.V Series & Parallel.

#

P. Rule .

Circuits can be generalized into two specific patterns/relations that can occur between its constituent components:

Rather amusingly, as seen in Rule [[[resistor[[[ and Rule [[[capacitor[[[, the equations for equivalent resistance and equivalent capacitance are reversed with respect to series and parallel.

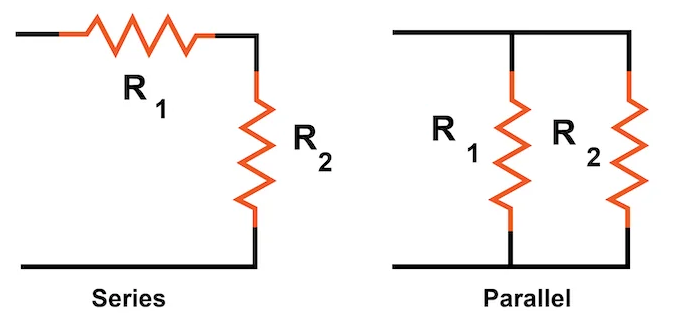

Below, there can be seen an example of resistors in series and parallel. Note that the same patterns hold for capacitors and all other components that may get into series and parallel:

Resistors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of AllAboutCircuits.

- Series: A situation between two electrical components in which the charge going through the first component must go through the second component. E.g., the components form a direct path with one another.

- Parallel: A situation between two electrical components in which the charge, as a result of a junction, will either go through one component or the other. The paths of the two components will then reconverge without going through another element.

Rather amusingly, as seen in Rule [[[resistor[[[ and Rule [[[capacitor[[[, the equations for equivalent resistance and equivalent capacitance are reversed with respect to series and parallel.

Below, there can be seen an example of resistors in series and parallel. Note that the same patterns hold for capacitors and all other components that may get into series and parallel:

Resistors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of AllAboutCircuits.

# Set: The particular parameterized region in which the components in series or parallel are located. The 'set' of the left circuit in the image shown at the bottom of Rule [[[-1 extends from the wire directly before R1 to the wire directly after R2.

The total Voltage of a 'set' in series only reflects the electric potential difference between those beginning and ending points - not the electric potential difference of the circuit as a whole (though, if the beginning and ending wires connect to the terminals, the Voltage of set will indeed be the Voltage of the circuit).

# Equivalent Resistance: Typically denoted using Req, Equivalent Resistance is the total summed values of all resistances within a circuit (measured in Ohms), summed with respect to their nature as resistors in series or parallel (see Rule [[[full analysis[[[). It is calculated using a substitution of the VCR Law.

The "Equivalent Resistance" of two or a specific set of resistors is just the summed total of those specific resistors, excluding all others in the circuit.

# Equivalent Capacitance: Typically denoted using Ceq, Equivalent Capacitance is the total summed values of all capacitances within a circuit (measured in Farads), summed with respect to their nature as capacitors in series or parallel (see Rule [[[full analysis[[[). It is calculated using a substitution of the capacitance equation (Rule 213).

The "Equivalent Capacitance" of two or a specific set of capacitors is just the summed total of those specific capacitors, excluding all others in the circuit.

# Junction: A point in which the wire of a circuit splits into two or more paths.

All parallel sections of a circuit have a diverging junction and a reconverging junction, specifically only involving a splitting into two paths/wires max - see Rule [[[big original one[[[.

#

P. Rule .

Resistors in Series & Parallel (Full Analysis):

Resistors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of AllAboutCircuits.

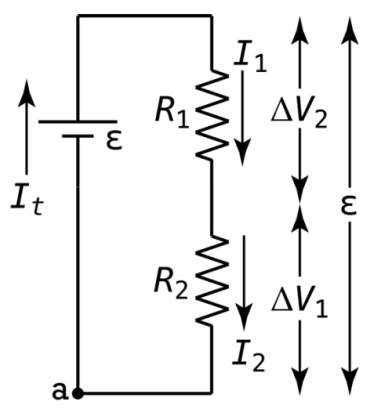

The left circuit above depicts two resistors in series, while the right circuit depicts two resistors in parallel.

Finding Equivalent Resistance for series and parallel sets requires finding other relationships, involving the likes of electric potential energy and current, in order to cancel out values using the VCR Law. See the "Series" and "Parallel" sections below for how this is done, and see Rule [[[ for a truncated version that only includes the equations for quick reference.

IT = I1 = I2, where I1 & I2 are the currents running through the two resistors, and IT is the general current running through the terminals of the battery.

When the two resistors are in series, the electric potential difference between the wire directly before the first resistor and the wire directly after the second resistor (which would be the wires connected to the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit) is equivalent to to the summed electric potential difference across the two resistors.

In short, as depicted below, Ɛ = ΔV1 + ΔV2, with Ɛ being ΔVset when there are more components in the circuit than just the two resistors.

A simple circuit in which two resistors are in series. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

By substituting in values from the VCR Law into the aforementioned equation, and then canceling out current (since the current is equal everywhere in series), the following equation can be established for equivalent resistance of a particular resistor set (for an 'n' number of resistors in series):

$$R_{\text{set series}} = \sum_n R_n = R_1 + R_2 + \dots$$

Thus, when a resistor is added into a series, the equivalent resistance increases.

ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

As for the current that moves through the split paths of a junction, it cannot be assumed that the current will split evenly between the two paths. In fact, all that is known about the individual path currents is the conservation of charge, delineated in the following equation:

It = I1 + I2

It, of course, is referring to the current before the diverging junction and after the converging junction. It is only ever represents the current running through the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit than the resistors in parallel.

In the same manner as was done before for series (now simply using different variables), the values of the VCR equation can be substituted into the above equation, and then have Voltage canceled out everywhere (since it was previously shown to be the same across every component). Thus, the following equation can be established, describing the equivalent resistance of 'n' resistors in parallel:

$$R_{\text{set parallel}} = \left( \sum_n \frac{1}{R_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

I.E., for resistors in parallel, the equivalent resistance is equal to the inverse of the sum of the inverses of all resistors in the set. Remember that in order to be parallel, there must only be one component on each split path before they reconverge.

Thus, when a resistor is added in parallel, the equivalent resistance decreases.

Resistors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of AllAboutCircuits.

The left circuit above depicts two resistors in series, while the right circuit depicts two resistors in parallel.

Finding Equivalent Resistance for series and parallel sets requires finding other relationships, involving the likes of electric potential energy and current, in order to cancel out values using the VCR Law. See the "Series" and "Parallel" sections below for how this is done, and see Rule [[[ for a truncated version that only includes the equations for quick reference.

Resistors in Series:

When two resistors are in series, the current running through them is the same:IT = I1 = I2, where I1 & I2 are the currents running through the two resistors, and IT is the general current running through the terminals of the battery.

When the two resistors are in series, the electric potential difference between the wire directly before the first resistor and the wire directly after the second resistor (which would be the wires connected to the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit) is equivalent to to the summed electric potential difference across the two resistors.

In short, as depicted below, Ɛ = ΔV1 + ΔV2, with Ɛ being ΔVset when there are more components in the circuit than just the two resistors.

A simple circuit in which two resistors are in series. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

By substituting in values from the VCR Law into the aforementioned equation, and then canceling out current (since the current is equal everywhere in series), the following equation can be established for equivalent resistance of a particular resistor set (for an 'n' number of resistors in series):

$$R_{\text{set series}} = \sum_n R_n = R_1 + R_2 + \dots$$

Thus, when a resistor is added into a series, the equivalent resistance increases.

Resistors in Parallel:

When resistors are in parallel, the electric potential difference across each resistor is equal to that of the electric potential difference between the wire before the diverging junction and the wire after the reconverging junction:ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

As for the current that moves through the split paths of a junction, it cannot be assumed that the current will split evenly between the two paths. In fact, all that is known about the individual path currents is the conservation of charge, delineated in the following equation:

It = I1 + I2

It, of course, is referring to the current before the diverging junction and after the converging junction. It is only ever represents the current running through the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit than the resistors in parallel.

In the same manner as was done before for series (now simply using different variables), the values of the VCR equation can be substituted into the above equation, and then have Voltage canceled out everywhere (since it was previously shown to be the same across every component). Thus, the following equation can be established, describing the equivalent resistance of 'n' resistors in parallel:

$$R_{\text{set parallel}} = \left( \sum_n \frac{1}{R_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

I.E., for resistors in parallel, the equivalent resistance is equal to the inverse of the sum of the inverses of all resistors in the set. Remember that in order to be parallel, there must only be one component on each split path before they reconverge.

Thus, when a resistor is added in parallel, the equivalent resistance decreases.

#

P. Rule .

Resistors in Series & Parallel (Truncated):

ΔVset = ΔV1 + ΔV2

$$R_{\text{set series}} = \sum_n R_n = R_1 + R_2 + \dots$$

ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2 $$R_{\text{set parallel}} = \left( \sum_n \frac{1}{R_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

Series:

IT = I1 = I2ΔVset = ΔV1 + ΔV2

$$R_{\text{set series}} = \sum_n R_n = R_1 + R_2 + \dots$$

Parallel:

It = I1 + I2ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2 $$R_{\text{set parallel}} = \left( \sum_n \frac{1}{R_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

#

P. Rule .

Capacitors in Series & Parallel (Full Analysis):

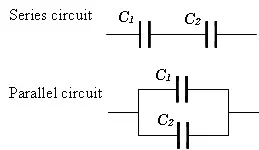

Capacitors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of Electric Shocks.

The top circuit above depicts two capacitors in series, while the bottom circuit depicts two capacitors in parallel.

Finding Equivalent Capacitance for series and parallel sets requires finding other relationships, involving the likes of electric potential energy and charge, in order to cancel out values using the capacitance equation of Rule 213. See the "Series" and "Parallel" sections below for how this is done, and see Rule [[[ for a truncated version that only includes the equations for quick reference.

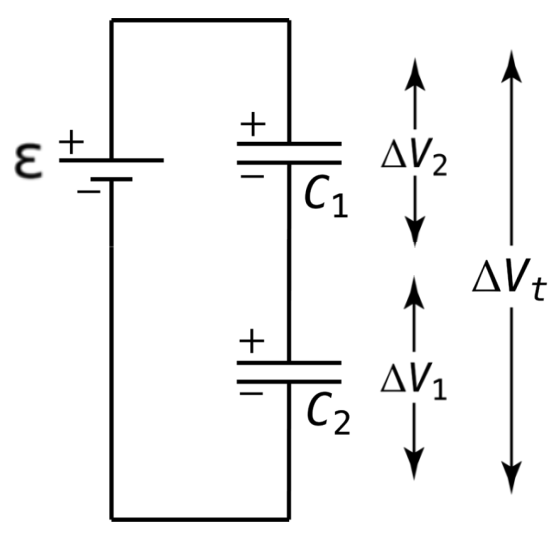

When the two capacitors are in series, the electric potential difference between the wire directly before the first capacitor and the wire directly after the second capacitor (which would be the wires connected to the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit) is equivalent to to the summed electric potential difference across the two capacitors. In short, as depicted below, Ɛ = ΔV1 + ΔV2, with Ɛ being ΔVset when there are more components in the circuit than just the two capacitors.

A simple circuit in which two capacitors are in series. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

As such, since the charges moved by the battery will have to pass through the plates of both capacitors equally, the magnitude of the charge is same for each capacitor:

Qset = Q1 = Q2

Finally, by substituting in values from the standard capacitance equation (Rule 213) into the aforementioned equation, and then canceling out charge (since charge is equal everywhere in series), the following equation can be established for equivalent capacitance of a particular capacitor set (for an 'n' number of capacitors in series):

$$C_{\text{set series}} = \left( \sum_{n} \frac{1}{C_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

I.E., for capacitors in series, the equivalent capacitance is equal to the inverse of the sum of the inverses of all capacitors in the set.

Thus, when a capacitor is added in series, the equivalent capacitance decreases.

ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

As for the current that moves through the split paths of a junction, it cannot be assumed that the current will split evenly between the two paths. In fact, all that is known about the individual path currents is the conservation of charge, delineated in the following equation:

It = I1 + I2

It, of course, is referring to the current before the diverging junction and after the converging junction. It is only ever represents the current running through the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit than the capacitors in parallel.

Furthermore, because the charges moved by the battery to the junction are going to be split between the two paths (between the two capacitors), the charge moved by the battery to the diverging junction (and by conservation of charge, the charge at the converging junction) is equal to the sum of charges across each individual capacitor:

Qset = Q1 + Q2 + ...

The values of the capacitance equation can then be substituted in for charge, leaving only Voltage and Capacitance. Since electric potential energy has already been determined to be the same for all values, it can be canceled out, leaving only the following equation for the equivalent capacitance of a set of 'n' capacitors in parallel:

$$C_{\text{set parallel}} = \sum_{n} C_n = C_1 + C_2 + \dots$$

Thus, when a capacitor is added in parallel, the equivalent capacitance increases.

Capacitors in Series and Parallel. Courtesy of Electric Shocks.

The top circuit above depicts two capacitors in series, while the bottom circuit depicts two capacitors in parallel.

Finding Equivalent Capacitance for series and parallel sets requires finding other relationships, involving the likes of electric potential energy and charge, in order to cancel out values using the capacitance equation of Rule 213. See the "Series" and "Parallel" sections below for how this is done, and see Rule [[[ for a truncated version that only includes the equations for quick reference.

Capacitors in Series:

When two capacitors are in series, the current running through them is the same: IT = I1 = I2, where I1 & I2 are the currents running through the two capacitors, and IT is the general current running through the terminals of the battery.When the two capacitors are in series, the electric potential difference between the wire directly before the first capacitor and the wire directly after the second capacitor (which would be the wires connected to the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit) is equivalent to to the summed electric potential difference across the two capacitors. In short, as depicted below, Ɛ = ΔV1 + ΔV2, with Ɛ being ΔVset when there are more components in the circuit than just the two capacitors.

A simple circuit in which two capacitors are in series. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

As such, since the charges moved by the battery will have to pass through the plates of both capacitors equally, the magnitude of the charge is same for each capacitor:

Qset = Q1 = Q2

Finally, by substituting in values from the standard capacitance equation (Rule 213) into the aforementioned equation, and then canceling out charge (since charge is equal everywhere in series), the following equation can be established for equivalent capacitance of a particular capacitor set (for an 'n' number of capacitors in series):

$$C_{\text{set series}} = \left( \sum_{n} \frac{1}{C_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

I.E., for capacitors in series, the equivalent capacitance is equal to the inverse of the sum of the inverses of all capacitors in the set.

Thus, when a capacitor is added in series, the equivalent capacitance decreases.

Capacitors in Parallel:

When capacitors are in parallel, the electric potential difference across each capacitor is equal to that of the electric potential difference between the wire before the diverging junction and the wire after the reconverging junction:ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

As for the current that moves through the split paths of a junction, it cannot be assumed that the current will split evenly between the two paths. In fact, all that is known about the individual path currents is the conservation of charge, delineated in the following equation:

It = I1 + I2

It, of course, is referring to the current before the diverging junction and after the converging junction. It is only ever represents the current running through the terminals if there are no other components in the circuit than the capacitors in parallel.

Furthermore, because the charges moved by the battery to the junction are going to be split between the two paths (between the two capacitors), the charge moved by the battery to the diverging junction (and by conservation of charge, the charge at the converging junction) is equal to the sum of charges across each individual capacitor:

Qset = Q1 + Q2 + ...

The values of the capacitance equation can then be substituted in for charge, leaving only Voltage and Capacitance. Since electric potential energy has already been determined to be the same for all values, it can be canceled out, leaving only the following equation for the equivalent capacitance of a set of 'n' capacitors in parallel:

$$C_{\text{set parallel}} = \sum_{n} C_n = C_1 + C_2 + \dots$$

Thus, when a capacitor is added in parallel, the equivalent capacitance increases.

#

P. Rule .

Capacitors in Series & Parallel (Truncated):

ΔVset = ΔV1 + ΔV2

Qset = Q1 = Q2 $$C_{\text{set series}} = \left( \sum_{n} \frac{1}{C_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

Qset = Q1 + Q2 + ... $$C_{\text{set parallel}} = \sum_{n} C_n = C_1 + C_2 + \dots$$

Series:

IT = I1 = I2ΔVset = ΔV1 + ΔV2

Qset = Q1 = Q2 $$C_{\text{set series}} = \left( \sum_{n} \frac{1}{C_n} \right)^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \dots \right)^{-1}$$

Parallel:

IT = I1 + I2ΔVset = ΔV1 = ΔV2

Qset = Q1 + Q2 + ... $$C_{\text{set parallel}} = \sum_{n} C_n = C_1 + C_2 + \dots$$

XVIII.VI Circuitry Conservation Principles.

Kirchhoff's Laws, hereafter referred to as the Circuitry Conservation Principles (CCP), are a set of two rules that describe basic characteristics about circuitry that can be applied in practically all circumstances (all circumstances that will be faced by the junior physicist).

There are two fundamental rules of the CCP that must always be kept in mind when doing circuitry problems: the Loop Rule and the Junction Rule, described in Rule [[[+1 and Rule [[[+2, respectively.