These are my complete notes for Gravitation in Classical Mechanics.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Gravitation (Classical Mechanics)

X. Gravitation

X.I Laws of Motion.

#

P. Rule .

Universal Law of Gravitation: VECTOR.

Units: Newtons. It is in the same form as Fg, as will be described.

Equation:

$$F_g = \frac{G \times m_1 \times m_2}{r^2}$$

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

m1 = Mass of the first object.

m2 = Mass of the second object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

Definition: A force of gravitational attraction exists for any two objects, not just an object and the Earth. The equation to determine this force is Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation.

The old force of gravity equation, "Fg = mg" or whatever, is a planet-specific equation, usable only on objects close to a planet and using that planet as one of the masses. Thus, if an object moves from a planet/asteroid a distance that is a significant portion of the planet's radius, then the Universal Law of Gravitation must be used instead of mg. The Law of Gravitation, however, is always correct in all scenarios, including those involving planets.

The given equation provides only the magnitude of the gravitational attraction between two objects, which is always an attractive force that pulls entities together. However, when finding a balance between two objects, like in a problem in which one must calculate an object's placement between two objects of different masses, such that the two pulls in opposite directions result in the object remaining in place (or any problem that requires calculating multiple gravitational pulls), setting a pull in a particular direction to be positive or negative (in relation to another pull) is perfectly fine, and can be necessary for pulls to cancel out (i.e., for them to be equal & opposite).

Units: Newtons. It is in the same form as Fg, as will be described.

Equation:

$$F_g = \frac{G \times m_1 \times m_2}{r^2}$$

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

m1 = Mass of the first object.

m2 = Mass of the second object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

Definition: A force of gravitational attraction exists for any two objects, not just an object and the Earth. The equation to determine this force is Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation.

The old force of gravity equation, "Fg = mg" or whatever, is a planet-specific equation, usable only on objects close to a planet and using that planet as one of the masses. Thus, if an object moves from a planet/asteroid a distance that is a significant portion of the planet's radius, then the Universal Law of Gravitation must be used instead of mg. The Law of Gravitation, however, is always correct in all scenarios, including those involving planets.

The given equation provides only the magnitude of the gravitational attraction between two objects, which is always an attractive force that pulls entities together. However, when finding a balance between two objects, like in a problem in which one must calculate an object's placement between two objects of different masses, such that the two pulls in opposite directions result in the object remaining in place (or any problem that requires calculating multiple gravitational pulls), setting a pull in a particular direction to be positive or negative (in relation to another pull) is perfectly fine, and can be necessary for pulls to cancel out (i.e., for them to be equal & opposite).

# Alternate Definition of Tangential Velocity for Gravitation:

When Gravitation is the only force acting upon an object (such as if the object is in orbit around a planet/asteroid), then an alternate definition of tangential velocity can be created by isolating velocity: $$V_t = \sqrt{\dfrac{G \times m}{r}}$$

# Parallax: When the position of an object appears to differ when viewed from different locations.

# Geocentric Model: The ancient model of the solar system in which a stationary Earth was at the center, with the sun and planets orbiting around it. This model was formalized by Ptolemy in the 1st century A.D. (see A. Rule 18).

# Heliocentric Model: A model of the solar system (widely accepted) in which the Sun is at the center, with the Earth and planets revolving around it. This model was proposed by Copernicus in 1543 (see A. Rule 22), supported by Celestial observations by Tycho Brahe in the late 1500s (see A. Rule 25), and given a mathematical basis by Johannes Kepler in the early 1600s (see A. Rule 26), who had been worked off of the data of Brahe.

#

P. Rule .

Kepler's Three Laws of Planetary Motion were developed over the course of 20 years of hardcore analysis of the data of Tycho Brahe. They are not too complex:

Law of Planetary Motion #1 - Law of Orbits

"Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one foci/focus point."

The path of an object through space is called its orbit, and has varying degrees of ellipticallity (known as eccentricity). The foci will change their postion depending on the size/nature of the ellipse.

Whereas a circle only has one special point (the center), in an ellipse there are TWO special points, known as the foci, or the focus points of the ellipse. The sum of the distance from the focus points to any position on the ellipse is always the same:

An animated ellipse to illustrate that the sum of the distances from a point to the foci is constant. Courtesy of the UTSA.

As seen above, r1 + r2 = 2a. Always.

The widest diameter of the ellipse is called its Major Axis, while half that distance, the distance from the center of the ellipse from end to end, is called the Semimajor Axis. The smallest diameter of the ellipse is the Minor Axis (of Symmetry), perpendicular to the Major Axis, and it has two semimajor axes at either side of the center as well:

The Major Axis (2a) – the longest diameter of an ellipse, each end point is called a vertex.

The Minor Axis (2b) – the shortest diameter of an ellipse, each end point is called a co-vertex.

The Semimajor Axis (a) – Half of the major axis.

The Semiminor Axis (b) – Half of the minor axis.

Eccentricity (e) – the distance between the two focal points, F1 and F2, divided by the length of the major axis.

(ae) – the distance between one of the focal points and the centre of the ellipse (the length of the Semimajor axis multiplied by the eccentricity). Courtesy of the Science & Math Zone.

The shape/roundness of an ellipse depends on how close together the two foci are, compared with the Major Axis. The ratio of the distance between the foci to the length of the major axis is called the Eccentricity of the ellipse. The equation for eccentricity can be derived as e = (c / a), where a is the length of the semimajor axis and c is the distance between the center of the ellipse to the foci.

If the eccentricity is zero, then the foci will be in the same spot and the ellipse will be a circle. Thus, in elliptical terms, a circle is an ellipse of zero eccentricity with the Semimajor axis as the radius.

The greater the eccentricity, the more elongated the ellipse, up to a maximum eccentricity of 1.0, which is just a flat line. The size and shape of an ellipse are completely specified by its Semimajor axis and its Eccentricity.

Law of Planetary Motion #1 - Law of Orbits

"Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one foci/focus point."

The path of an object through space is called its orbit, and has varying degrees of ellipticallity (known as eccentricity). The foci will change their postion depending on the size/nature of the ellipse.

Whereas a circle only has one special point (the center), in an ellipse there are TWO special points, known as the foci, or the focus points of the ellipse. The sum of the distance from the focus points to any position on the ellipse is always the same:

An animated ellipse to illustrate that the sum of the distances from a point to the foci is constant. Courtesy of the UTSA.

As seen above, r1 + r2 = 2a. Always.

The widest diameter of the ellipse is called its Major Axis, while half that distance, the distance from the center of the ellipse from end to end, is called the Semimajor Axis. The smallest diameter of the ellipse is the Minor Axis (of Symmetry), perpendicular to the Major Axis, and it has two semimajor axes at either side of the center as well:

The Major Axis (2a) – the longest diameter of an ellipse, each end point is called a vertex.

The Minor Axis (2b) – the shortest diameter of an ellipse, each end point is called a co-vertex.

The Semimajor Axis (a) – Half of the major axis.

The Semiminor Axis (b) – Half of the minor axis.

Eccentricity (e) – the distance between the two focal points, F1 and F2, divided by the length of the major axis.

(ae) – the distance between one of the focal points and the centre of the ellipse (the length of the Semimajor axis multiplied by the eccentricity). Courtesy of the Science & Math Zone.

The shape/roundness of an ellipse depends on how close together the two foci are, compared with the Major Axis. The ratio of the distance between the foci to the length of the major axis is called the Eccentricity of the ellipse. The equation for eccentricity can be derived as e = (c / a), where a is the length of the semimajor axis and c is the distance between the center of the ellipse to the foci.

If the eccentricity is zero, then the foci will be in the same spot and the ellipse will be a circle. Thus, in elliptical terms, a circle is an ellipse of zero eccentricity with the Semimajor axis as the radius.

The greater the eccentricity, the more elongated the ellipse, up to a maximum eccentricity of 1.0, which is just a flat line. The size and shape of an ellipse are completely specified by its Semimajor axis and its Eccentricity.

#

P. Rule .

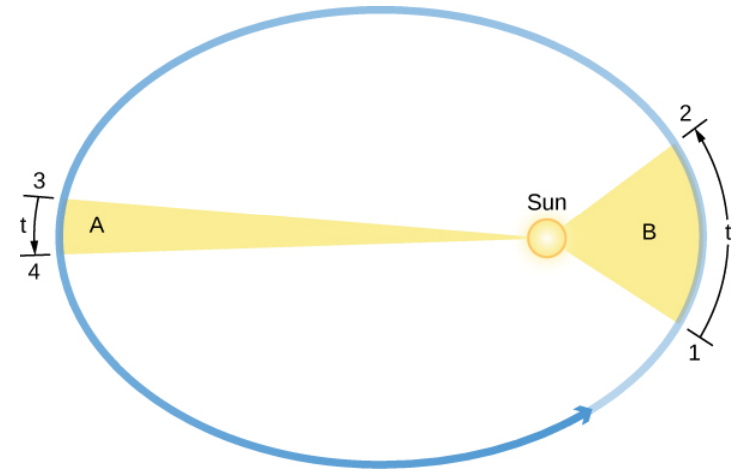

Law of Planetary Motion #2 - Law of Areas

"Each planet moves such that an imaginary line drawn between the sun and the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time periods."

Kepler determined that Mars moves faster as it comes closer to the Sun, and slows down as it pulls away from the Sun. Therefore, objects in orbit are patently NOT in Uniform Acceleration, unless they have an eccentricity of 0.

Visualize an elastic band connecting a celestial body with the Sun. As the body gets farther from the sun, the band gets stretched, and thus moves slower until the band will pull it back to the sun. When it is closer to the sun, the band is not stretched as much and thus moves rapidly. Additionally, if you were to imagine the area sweeped in the ellipse (centered from the sun) by the orbit, then, given equal intervals of time, any two sweeped areas of the orbit will be equal.

The orbital speed of a planet traveling around the Sun (the circular object inside the ellipse) varies in such a way that in equal intervals of time (t), a line between the Sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas (A and B). Note that the eccentricities of the planets’ orbits in the solar system are substantially less than shown here.

While a circular orbit would cause a planet to move at the same speed throughout its orbit, the differing speeds of the planets as they move make it evident that their orbits are elliptical.

"Each planet moves such that an imaginary line drawn between the sun and the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time periods."

Kepler determined that Mars moves faster as it comes closer to the Sun, and slows down as it pulls away from the Sun. Therefore, objects in orbit are patently NOT in Uniform Acceleration, unless they have an eccentricity of 0.

Visualize an elastic band connecting a celestial body with the Sun. As the body gets farther from the sun, the band gets stretched, and thus moves slower until the band will pull it back to the sun. When it is closer to the sun, the band is not stretched as much and thus moves rapidly. Additionally, if you were to imagine the area sweeped in the ellipse (centered from the sun) by the orbit, then, given equal intervals of time, any two sweeped areas of the orbit will be equal.

The orbital speed of a planet traveling around the Sun (the circular object inside the ellipse) varies in such a way that in equal intervals of time (t), a line between the Sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas (A and B). Note that the eccentricities of the planets’ orbits in the solar system are substantially less than shown here.

While a circular orbit would cause a planet to move at the same speed throughout its orbit, the differing speeds of the planets as they move make it evident that their orbits are elliptical.

# Astronomical Unit: The average distance between the Sun and the Earth, defined as 149,597,870,700 meters.

#

P. Rule .

Law of Planetary Motion #3 - Law of Periods

"The square of the orbital period of any planet is proportional to the cube of the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbit; in other words, T² ∝ a³."

There are two equations:

The First Equation is best used when comparing two bodies orbiting the same central object, like the Earth and an Asteroid. The ratio can be set up as (TAsteroid / TEarth)² = (rAsteroid / rEarth)³, for example. In such cases, put the new object in the numerator on both sides, as to ease isolation.

The Second Equation is preferable when the orbital period or distance of the reference orbit is unknown, or if the central mass being orbited changes.

E.g., the 1st equation is best suited when the orbited mass already has a reference orbit that can be used (and 3/4th of the variables are known), and the 2nd equation for all other circumstances.

1. T² ∝ a³

2. T² = (4π² / GM) × a³

T - The "Orbital Period", or the time it takes the orbit to record one revolution around the Primary. Measured in Earth-years.

a - The Semimajor Axis (see Rule 141). This is the average distance between the orbiting object and the primary, and is measured in AU.

G - The Universal Gravitational Constant (6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²))

M - Mass of the Primary (e.g., the Sun or another star), except in binary systems - in this case, M represents the total mass of the objects.

The equation is derived from the Law of Gravitation and an inward force summation.

"The square of the orbital period of any planet is proportional to the cube of the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbit; in other words, T² ∝ a³."

There are two equations:

The First Equation is best used when comparing two bodies orbiting the same central object, like the Earth and an Asteroid. The ratio can be set up as (TAsteroid / TEarth)² = (rAsteroid / rEarth)³, for example. In such cases, put the new object in the numerator on both sides, as to ease isolation.

The Second Equation is preferable when the orbital period or distance of the reference orbit is unknown, or if the central mass being orbited changes.

E.g., the 1st equation is best suited when the orbited mass already has a reference orbit that can be used (and 3/4th of the variables are known), and the 2nd equation for all other circumstances.

1. T² ∝ a³

2. T² = (4π² / GM) × a³

T - The "Orbital Period", or the time it takes the orbit to record one revolution around the Primary. Measured in Earth-years.

a - The Semimajor Axis (see Rule 141). This is the average distance between the orbiting object and the primary, and is measured in AU.

G - The Universal Gravitational Constant (6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²))

M - Mass of the Primary (e.g., the Sun or another star), except in binary systems - in this case, M represents the total mass of the objects.

The equation is derived from the Law of Gravitation and an inward force summation.

# Geosynchronous/Geostationary Orbit: A state of an object orbiting the Earth where it is always positioned directly over the same spot on the Earth. In order for this to be the case, the orbiting body must be directly over the equator.

The orbited body has to be the Earth, for otherwise, it would merely be a Stationary or Synchronous orbit.

# MEarth (Mass of the Earth, Earth Mass): 5.9723 × 10²⁴ kg.

# Equatorial Radius of Earth: 6.378 × 10⁶ m.

#

P. Rule .

Weightlessness:

In order for TRUE weightlessness, the force of gravity acting on an object (the weight) must be equal to zero, and thus the acceleration due to gravity must equal to zero.

Given the Universal Law of Gravitation, the only way to have the force of gravity on an object equal zero is to have infinite amount of distance between the object and everything else in universe, which is impossible. Every particle is exerting is gravitationally attracted to everything else.

Other means of reaching weightlessness while more than one object exists in the universe include placing the object in the center of a uniform spherical shell, in which case the object would be perfectly pulled in every direction to remain stationary. Similarly, the simple case of placing the object between two objects, so that the object will be equally pulled in opposite directions, will leave the object stationary.

Of course, for the "apparent weightlessness" that is simply falling, only the normal force needs to be zero, as is the case with the International Space Station. See Rule 78 for the derivation. Apparent Weightlessness can be simply defined as a state in which zero g-Forces in any direction are acting on an object (zero net g-forces (see Rule 145)).

In order for TRUE weightlessness, the force of gravity acting on an object (the weight) must be equal to zero, and thus the acceleration due to gravity must equal to zero.

Given the Universal Law of Gravitation, the only way to have the force of gravity on an object equal zero is to have infinite amount of distance between the object and everything else in universe, which is impossible. Every particle is exerting is gravitationally attracted to everything else.

Other means of reaching weightlessness while more than one object exists in the universe include placing the object in the center of a uniform spherical shell, in which case the object would be perfectly pulled in every direction to remain stationary. Similarly, the simple case of placing the object between two objects, so that the object will be equally pulled in opposite directions, will leave the object stationary.

Of course, for the "apparent weightlessness" that is simply falling, only the normal force needs to be zero, as is the case with the International Space Station. See Rule 78 for the derivation. Apparent Weightlessness can be simply defined as a state in which zero g-Forces in any direction are acting on an object (zero net g-forces (see Rule 145)).

#

P. Rule .

G-Forces:

The number of "G's" an object has is a ratio of the acceleration experienced by the object with respect to the ordinary acceleration experienced on Earth: If you have a vertical g-force of 2, you are experiencing an apparent weight double to what it normally is.

Since life on Earth dictates there is always a vertical acceleration due to Gravity, a g-force of 1 vertically and 0 horizontally is the "normal", where everything should be as it should. This is the state encountered when at rest.

To have a G-force in the horizontal direction would mean you are doing something very strange, since humans do not usually experience weight horizontally. Generally, the fastest cars only go slightly more than 1 g horizontally at top accelerations. There are two equations that can be used to determine the total number of g-Forces acting on an object:

Vertical # of g-Forces: (FN / FgEarth)

Horizontal # of g-Forces: (ax / gEarth)

FN = The Normal Force an object has, such as that produced by rocket fuel when launching upward.

FgEarth = The gravitational force caused by the Earth.

ax = Acceleration of an object in the x-direction.

gEarth = The acceleration due to gravity of the Earth.

The number of "G's" an object has is a ratio of the acceleration experienced by the object with respect to the ordinary acceleration experienced on Earth: If you have a vertical g-force of 2, you are experiencing an apparent weight double to what it normally is.

Since life on Earth dictates there is always a vertical acceleration due to Gravity, a g-force of 1 vertically and 0 horizontally is the "normal", where everything should be as it should. This is the state encountered when at rest.

To have a G-force in the horizontal direction would mean you are doing something very strange, since humans do not usually experience weight horizontally. Generally, the fastest cars only go slightly more than 1 g horizontally at top accelerations. There are two equations that can be used to determine the total number of g-Forces acting on an object:

Vertical # of g-Forces: (FN / FgEarth)

Horizontal # of g-Forces: (ax / gEarth)

FN = The Normal Force an object has, such as that produced by rocket fuel when launching upward.

FgEarth = The gravitational force caused by the Earth.

ax = Acceleration of an object in the x-direction.

gEarth = The acceleration due to gravity of the Earth.

#

P. Rule .

Gravitational Fields:

A field in which a force of gravitational attraction is present. Diagrams are drawn as so:

/>

/>

The gravitational fields of the Earth and the Moon.

The lines are Field Lines, and the strength of the field is represented by how close the lines are to one another. Since all the lines are pointed internally the centers of mass of the moon and the Earth, they illustrate constant downward gravitational fields.

The farther away from the planet, as depicted in the diagram, the more distant the field lines, and thus the weaker the gravitational force acting on the object. For a single object, gravitational field lines are always toward the center of mass of the object.

The equation for a g.f. when it has a constant value, like on Earth (generalizing), is

g = Fg / m

In a constant gravitational field, any object will produce the gravitational acceleration constant using this equation. On Earth, this is 9.81 m/s².

The non-constant gravitational field equation, which can be used for the gravitational field of any object, is:

g = (G × mo) / r²

g = The Gravitational Field, e.g. the gravitational attraction a mass exerts on the surrounding area. For non-constant fields (all real ones as distance increases from the mass), the field refers to the force experienced by an object (at any location) due to the gravitational pull of the mass. It is measured in N/kg, which simplifies to m/s².

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

mo = Mass of the object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

A field in which a force of gravitational attraction is present. Diagrams are drawn as so:

/>

/>The lines are Field Lines, and the strength of the field is represented by how close the lines are to one another. Since all the lines are pointed internally the centers of mass of the moon and the Earth, they illustrate constant downward gravitational fields.

The farther away from the planet, as depicted in the diagram, the more distant the field lines, and thus the weaker the gravitational force acting on the object. For a single object, gravitational field lines are always toward the center of mass of the object.

The equation for a g.f. when it has a constant value, like on Earth (generalizing), is

g = Fg / m

In a constant gravitational field, any object will produce the gravitational acceleration constant using this equation. On Earth, this is 9.81 m/s².

The non-constant gravitational field equation, which can be used for the gravitational field of any object, is:

g = (G × mo) / r²

g = The Gravitational Field, e.g. the gravitational attraction a mass exerts on the surrounding area. For non-constant fields (all real ones as distance increases from the mass), the field refers to the force experienced by an object (at any location) due to the gravitational pull of the mass. It is measured in N/kg, which simplifies to m/s².

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

mo = Mass of the object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

#

P. Rule .

Universal Gravitational Potential Energy

Whereas before, the only equation for PEg (mgh) referred to objects in a constant gravitational field, recent advancements have led to the development of a Universal equation, which can provide the gravitational potential energy for any object in the universe, regardless of field:

Ug = -(G × m1 × m2) / (r)

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

m1 = Mass of the first object.

m2 = Mass of the second object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

As evident, the only differences between this equation and the Law of Gravitation is the negative and the r having a degree of '1' instead of '2'. While the equation for U.G.P.E. always produces a negative value, the change in U.G.P.E. can be positive. Furthermore, U.G.P.E. requires 2 objects to function.

Mixing and matching different forms of gravitational potential energy, such as in a conservation of mechanical energy, is forbidden. It is the law of the land. 'mgh' merely approximates the greater U.G.P.E. equation, and so must never be used alongside the greater equation in any circumstance.

You must only use one or the other. If which to use is ever in doubt (e.g., the object is leaving ground level), just use the U.G.P.E..

Whereas before, the only equation for PEg (mgh) referred to objects in a constant gravitational field, recent advancements have led to the development of a Universal equation, which can provide the gravitational potential energy for any object in the universe, regardless of field:

Ug = -(G × m1 × m2) / (r)

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

m1 = Mass of the first object.

m2 = Mass of the second object.

r = The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects, not the radius (unless it is by circumstance).

As evident, the only differences between this equation and the Law of Gravitation is the negative and the r having a degree of '1' instead of '2'. While the equation for U.G.P.E. always produces a negative value, the change in U.G.P.E. can be positive. Furthermore, U.G.P.E. requires 2 objects to function.

Mixing and matching different forms of gravitational potential energy, such as in a conservation of mechanical energy, is forbidden. It is the law of the land. 'mgh' merely approximates the greater U.G.P.E. equation, and so must never be used alongside the greater equation in any circumstance.

You must only use one or the other. If which to use is ever in doubt (e.g., the object is leaving ground level), just use the U.G.P.E..

# Binding Energy: The minimum energy or work necessary to completely remove one object from another object. This can be applied in both splitting an atom and launching a space rocket.

# Escape Velocity: The escape velocity of a planet is the minimum velocity at which an object can be launched and have it completely escape the gravitational attraction of a planet. If launched from the planet with a smaller velocity than the escape velocity, the object will eventually fall back to the planet.

The equation(s) for escape velocity (for any planet/celestial object) are:

$$ v_{\text{escape}} = \sqrt{\frac{2 G m_p}{R_p}} $$ $$ v_{\text{escape}} = \sqrt{2 a_p R} $$ G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

mp = Mass of the planet.

Rp = The Radius of the planet.

ap = The acceleration due to the gravitational pull of the planet on the body.

Choose whichever based on the variables you have. The first equation is derived as so. The second is more of a generalization, most applicable on the surface of a planet.

#

P. Rule .

The Principle of Superposition dictates the net gravitational force of one particle in a system of particles. The basic idea is that the gravitational forces acting on that specific particle, are individually computed from each of the other particles, and from there are summed.

The forces must always be summed vectorally, accounting for direction - see Rule 140.

The forces must always be summed vectorally, accounting for direction - see Rule 140.

#

P. Rule .

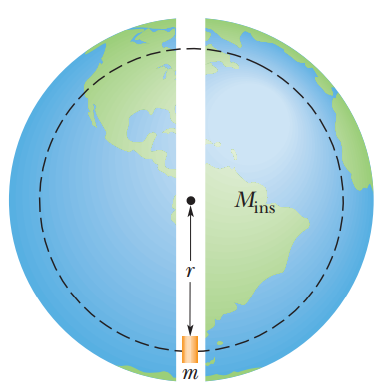

Internal Gravitation

Gravitational attraction INSIDE a planet, follows slightly different equations (though still derived from the base ones) that must be memorized. In doing this, 'r' will become less than the radius of the planet.

The Shell Theorem was formulated by Newton, and follows as so:

"A uniform spherical shell of matter attracts a particle that is outside the shell as if all the shell’s mass were concentrated at its center."

The Earth, and other planet/spherical celestial object, is a nest of shells, each shell individually attracting objects.

For the sake of the uber-idealized equations (that will determine the force of gravity while the object is inside the planet) working as accurately as possible, several assumptions need to be made:

An object traversing the Earth tunnel, with Earth meeting the three characteristics previously described. As the object goes deeper, its gravitational attraction will decrease as more mass becomes part of the outer shell, which does not act on the object (relatively).

Using a simple derivation, a revolutionary new equation can be determined for the gravitational force acting on any object that is within a planet:

Fg = (G × mo × mp × r) / R³

Fg = The force of gravitational attraction.

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

mo = Mass of the object.

mp = Mass of the planet/celestial body.

r = The distance of the object from the center of mass of the planet.

R = The actual radius of the planet.

Gravitational attraction INSIDE a planet, follows slightly different equations (though still derived from the base ones) that must be memorized. In doing this, 'r' will become less than the radius of the planet.

The Shell Theorem was formulated by Newton, and follows as so:

"A uniform spherical shell of matter attracts a particle that is outside the shell as if all the shell’s mass were concentrated at its center."

The Earth, and other planet/spherical celestial object, is a nest of shells, each shell individually attracting objects.

For the sake of the uber-idealized equations (that will determine the force of gravity while the object is inside the planet) working as accurately as possible, several assumptions need to be made:

- The planet, mp has a constant density.

- The object is capable of moving, without friction, through a tunnel drilled through the planet. Thus, the planet must also not be rotating.

- The only mass that causes a force on the object is the mass inside the sphere created by the object while it is radius r from the center. Thus, when the object is at the center, it will have no forces acting on it, and if it were 1 meter away, it will have a mass of radius 1 m exerting a gravitational force on it (see image).

"A uniform shell of matter exerts no net gravitational force on a particle located inside it."

While all the mass outside of r still causes a force of gravity on the object, because the force of gravity is proportional to the inverse square of the radius, all the forces of gravitational attraction outside of the internal sphere will cancel out.

An object traversing the Earth tunnel, with Earth meeting the three characteristics previously described. As the object goes deeper, its gravitational attraction will decrease as more mass becomes part of the outer shell, which does not act on the object (relatively).

Using a simple derivation, a revolutionary new equation can be determined for the gravitational force acting on any object that is within a planet:

Fg = (G × mo × mp × r) / R³

Fg = The force of gravitational attraction.

G = The Universal Gravitational Constant, or 6.67 x 10⁻¹¹ (N × m²) / (kg²).

mo = Mass of the object.

mp = Mass of the planet/celestial body.

r = The distance of the object from the center of mass of the planet.

R = The actual radius of the planet.