These are my complete notes for Rotational Motion in Classical Mechanics.

I color-coded my notes according to their meaning - for a complete reference for each type of note, see here (also available in the sidebar). All of the knowledge present in these notes has been filtered through my personal explanations for them, the result of my attempts to understand and study them from my classes and online courses. In the unlikely event there are any egregious errors, contact me at jdlacabe@gmail.com.

Summary of Rotational Motion (Classical Mechanics)

Table Of Contents

V. Rotational Motion.

V.I Angular & Tangential Velocity.

#

P. Rule .

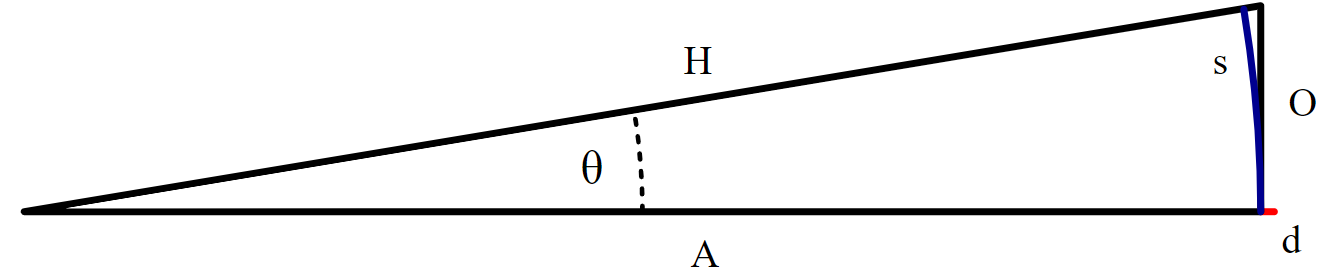

The position of an object in rotational motion can be determined in Cartesian and Polar coordinates, going back and forth using trigonometry. When an object is moving along a circle with a constant radius, the object undergoes an angular displacement (with regard to the Polar coordinates (r, θ)):

A section of a circle, showcasing arc-length (s), the angle (Δθ), but not the individual angles of the Hypotenuse and the adjacent leg, θF and θi. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Δθ = θF - θi

The curved linear distance the object would move when moving along an arc is called the arc length. It is the curved length on the side of the circle outside of the angular displacement Δθ. The equation for arc length is as follows:

s = r × Δθ

Where s is the arc length, r is the radius, and Δθ is the angular displacement. THE UNITS FOR ANGULAR DISPLACEMENT MUST BE IN RADIANS. CONVERT USING (π / 180) IF NEEDS BE.

A section of a circle, showcasing arc-length (s), the angle (Δθ), but not the individual angles of the Hypotenuse and the adjacent leg, θF and θi. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Δθ = θF - θi

The curved linear distance the object would move when moving along an arc is called the arc length. It is the curved length on the side of the circle outside of the angular displacement Δθ. The equation for arc length is as follows:

s = r × Δθ

Where s is the arc length, r is the radius, and Δθ is the angular displacement. THE UNITS FOR ANGULAR DISPLACEMENT MUST BE IN RADIANS. CONVERT USING (π / 180) IF NEEDS BE.

#

P. Rule .

π = 3.1, give or take. It refers to the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, and as an irrational number, it will go on forever. Since the formula for obtaining pi cancels out any dimensions in length (c/d = (86.9m)/(27.5m) ≈ 3.1415926...), the value of pi is in Radians, which is just a dimensionless placeholder unit. The abbreviation for Radians is 'rad'.

#

P. Rule .

While average linear velocity is conveyed as Vavg = (∆x / ∆t), average angular velocity is written as ωavg = (∆θ / ∆t), which can be represented in Radians per Second, Revolutions per Minute, Degrees per Millisecond, etc.

Radians per Second are most commonly used in Physics, while revolutions per minute is most used in Applicationism and "the real world".

Radians per Second are most commonly used in Physics, while revolutions per minute is most used in Applicationism and "the real world".

#

P. Rule .

The symbol for angular acceleration is α, which is very convenient considering how similar it looks to a. The average angular acceleration is equal to αavg = (∆ω / ∆t). Therefore, the units for angular acceleration are radians per second squared or revolutions per minute squared.

#

P. Rule .

Just like how an object can have uniformly accelerated motion, an object can also have uniformly angularly accelerated motion. This is written as U.α.M., instead of U.A.M., even though the alpha is lowercase. As with linear acceleration, the U.α.M. constants can be used when α is constant. All of the variables from U.A.M. must be converted into their angular form:

ωF, ωi, α, ∆θ, and ∆t.

Now, we can rewrite every U.A.M. equation using these variables:

ωF = ωi + (α × ∆t).

∆θ = (ωi × ∆t) + (1/2 × α × ∆t²)

ωF² = ωi² + (2 × α × ∆θ)

∆θ = (1/2) × (ωF + ωi) × ∆t

ALWAYS use radians in your calculations for U.α.M. equations. Additionally, remember that ωF and ωi are instantaneous angular velocities, as opposed to the average velocity (∆θ / ∆t).

ωF, ωi, α, ∆θ, and ∆t.

Now, we can rewrite every U.A.M. equation using these variables:

ωF = ωi + (α × ∆t).

∆θ = (ωi × ∆t) + (1/2 × α × ∆t²)

ωF² = ωi² + (2 × α × ∆θ)

∆θ = (1/2) × (ωF + ωi) × ∆t

ALWAYS use radians in your calculations for U.α.M. equations. Additionally, remember that ωF and ωi are instantaneous angular velocities, as opposed to the average velocity (∆θ / ∆t).

#

P. Rule .

Since angular velocity, angular acceleration, and change in angular position are vectors, they all have direction. However, since clockwise and counterclockwise are observer-dependent, we use the right-hand rule to determine direction.

# Tangential Velocity: The linear velocity of an object moving in a circle. Given by the equation vt = r × ω. Because it is LINEAR, you use m/s as your base units. Furthermore, notice that none of the values in the equation are vectors - this equation refers purely to the magnitudes of each variable.

#

P. Rule .

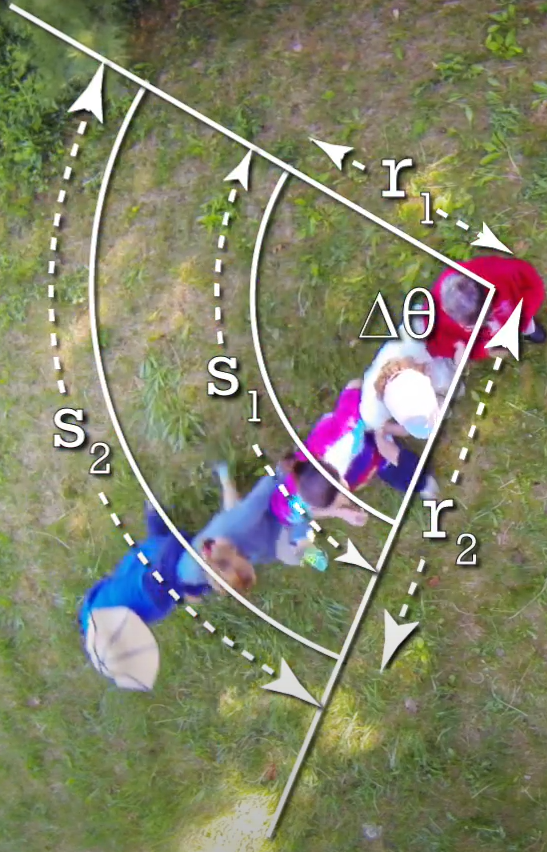

The farther along you go on the radius of a circle, the linear distance that point travels when moving through a circle, which is called arc length, will increase. This is in spite of the fact that the angular velocity and angular displacement is the same, regardless of radii length, as each point on the radius covers the same number of degrees in the same amount of time.

The path traveled by each point on the radius will form an internal circle, the point moving around the circumference of this circle. Each point on the radius has a linear velocity when it is moving in the circle, known as tangential velocity, which increases proportionally as the radius and arc length (defined by the formula s = r × Δθ) increase. The tangential velocity is given by the equation vt = r × ω, which, just like the arc length equation, requires radians. The angular velocity in the equation needs to be in radians per second.

See the different internal arc lengths that each radius-length has below:

A diagram of internal circles defined by different points on the radius, of which the arc length differs for the same change in θ. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

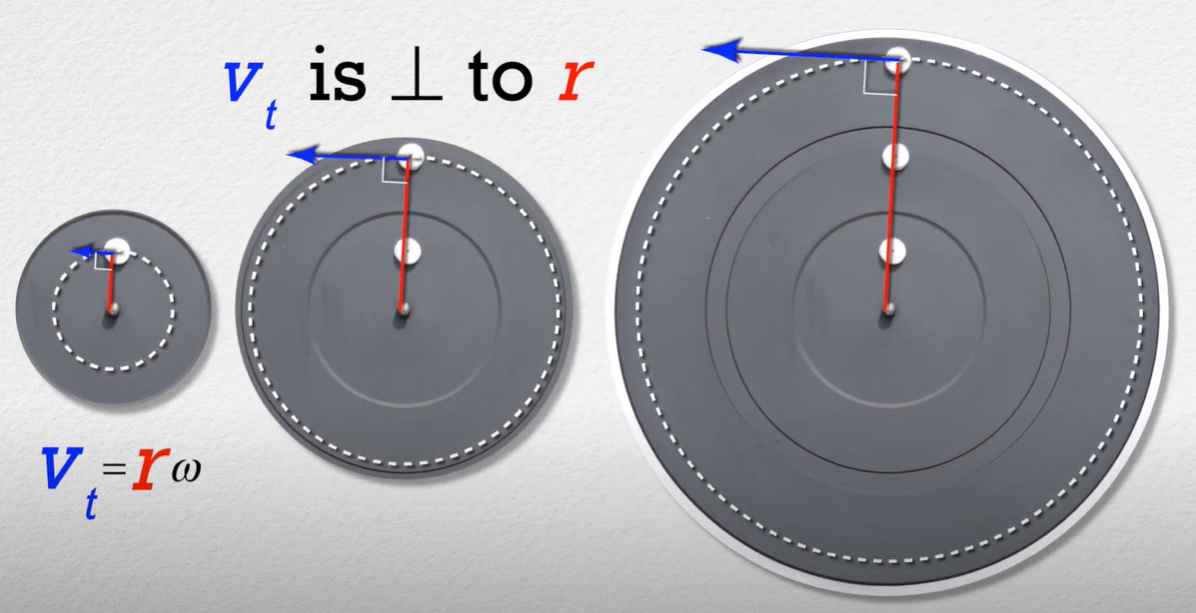

Tangential Velocity is named for how its velocity vector is tangent to the circumference of the circle, perpendicular to the radius. Tangential Acceleration is the exact same way:

The tangential velocity of three separate circle, increasing each time. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

The path traveled by each point on the radius will form an internal circle, the point moving around the circumference of this circle. Each point on the radius has a linear velocity when it is moving in the circle, known as tangential velocity, which increases proportionally as the radius and arc length (defined by the formula s = r × Δθ) increase. The tangential velocity is given by the equation vt = r × ω, which, just like the arc length equation, requires radians. The angular velocity in the equation needs to be in radians per second.

See the different internal arc lengths that each radius-length has below:

A diagram of internal circles defined by different points on the radius, of which the arc length differs for the same change in θ. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

Tangential Velocity is named for how its velocity vector is tangent to the circumference of the circle, perpendicular to the radius. Tangential Acceleration is the exact same way:

The tangential velocity of three separate circle, increasing each time. Courtesy of Flipping Physics.

#

P. Rule .

Tangential Acceleration is defined by the following equation:

at = r × α.

Like the equations for arc length and tangential velocity, you must use Radians as your angular quantity. Because it is LINEAR, you use m/s² as your base units. Furthermore, notice that none of the values in the equation are vectors - this equation refers purely to the magnitudes of each variable.

at = r × α.

Like the equations for arc length and tangential velocity, you must use Radians as your angular quantity. Because it is LINEAR, you use m/s² as your base units. Furthermore, notice that none of the values in the equation are vectors - this equation refers purely to the magnitudes of each variable.

#

P. Rule .

On the nature of Tangential Velocity (and others) as a vector:

Imagine a situation in which the radius and angular velocity of a point on the circle are both constant - This just means that the circle is rotating at a constant speed.

If this were to be the case, then the linear velocity of the radius, the tangential velocity, would still not be constant, even though tangential velocity is literally equal to the radius times the angular velocity. This is because tangential velocity is a vector with both magnitude and direction. While the magnitude would be constant, the direction of the tangential velocity would be constantly changing (perpendicular to the radius as it makes it revolution around the circle), and so tangential velocity itself would not be constant. Therefore, the radius has neither a tangential acceleration nor an angular acceleration.

Imagine a situation in which the radius and angular velocity of a point on the circle are both constant - This just means that the circle is rotating at a constant speed.

If this were to be the case, then the linear velocity of the radius, the tangential velocity, would still not be constant, even though tangential velocity is literally equal to the radius times the angular velocity. This is because tangential velocity is a vector with both magnitude and direction. While the magnitude would be constant, the direction of the tangential velocity would be constantly changing (perpendicular to the radius as it makes it revolution around the circle), and so tangential velocity itself would not be constant. Therefore, the radius has neither a tangential acceleration nor an angular acceleration.

V.II Centripetal Velocity.

"Radial Velocity" is just linear velocity, and "Radial Acceleration" refers to Centripetal Acceleration (below).

#

P. Rule .

There is ANOTHER linear acceleration apart from tangential acceleration - there are three total that matter. It is called Centripetal Acceleration, also known as Radial Acceleration. Look at these words:

"Centripetal Acceleration is the linear acceleration that causes the tangential velocity to change direction."

Utterly meaningless on their surface, searching for any possible knowledge in these words is an exercise in futility. However, beyond their nonsensical face-value, an elaboration of these words will reveal their value:

The word 'Centripetal' is derived from "centrum", meaning center, and "petere", meaning to seek. Centripetal acceleration is the acceleration that causes circular motion. Centripetal acceleration is always directed inward to the circle, toward the center. It is a center-seeking linear acceleration. The force inward is what causes circular motion - see Rule 49 for more information.

The equation for Centripetal Acceleration is as follows:

ac = (Vt²) / r

Notice that none of the values in the equation are vectors: this equation refers purely to the magnitudes of each variable.

Through the substitution of the substitution of the equation for Tangential velocity, we can simply the equation further:

= ((r × ω)² / r) = ((r² × ω²) / r) = r × ω²

Because it is LINEAR, you use m/s² as your base units.

"Centripetal Acceleration is the linear acceleration that causes the tangential velocity to change direction."

Utterly meaningless on their surface, searching for any possible knowledge in these words is an exercise in futility. However, beyond their nonsensical face-value, an elaboration of these words will reveal their value:

The word 'Centripetal' is derived from "centrum", meaning center, and "petere", meaning to seek. Centripetal acceleration is the acceleration that causes circular motion. Centripetal acceleration is always directed inward to the circle, toward the center. It is a center-seeking linear acceleration. The force inward is what causes circular motion - see Rule 49 for more information.

The equation for Centripetal Acceleration is as follows:

ac = (Vt²) / r

Notice that none of the values in the equation are vectors: this equation refers purely to the magnitudes of each variable.

Through the substitution of the substitution of the equation for Tangential velocity, we can simply the equation further:

= ((r × ω)² / r) = ((r² × ω²) / r) = r × ω²

Because it is LINEAR, you use m/s² as your base units.

#

P. Rule .

We can extrapolate the known information about circular centripetal acceleration to apply to any curved path an object may follow, and therefore any object moving on a curved path will experience a centripetal acceleration.

When going over the top of a hill or other circular object that can have its forces summed to form the centripetal force (see Rule 49), the normal force will be less than the force of gravity, since you feel less of a normal reaction force from the ground. This is why you feel weightless when you are driving over a hill!

When going over the top of a hill or other circular object that can have its forces summed to form the centripetal force (see Rule 49), the normal force will be less than the force of gravity, since you feel less of a normal reaction force from the ground. This is why you feel weightless when you are driving over a hill!

#

P. Rule .

The whole idea of centripetal acceleration and tangential velocity and acceleration and everything else in rotational motion is that all the equations use all the same variables, and you can connect what you have to what you need by repeatedly plugging in numbers into equations. For example, to find centripetal acceleration (equation below), you tangential velocity, which you need the average angular velocity for, and so on. To really instill this into your brain, stare at the equations for rotational motion until you imagine them every time you see a rotating circle. For a refresher on all three types of acceleration, watch this videos.

#

P. Rule .

By the nature of their equations, Tangential velocity requires the object to be in acceleration (either speeding up or slowing down as it goes around the circle), while Centripetal acceleration only needs the object to be going around in the circle at a constant rate.

#

P. Rule .

Newton's Second Law (see Rule 68) states that net force equals mass times acceleration, or ΣF = m × a. Since it has been determined (see Rule 46) that every object moving on a curved path will have centripetal acceleration, we can apply centripetal acceleration to Newton's Second Law and end up with the equation for Centripetal Force:

ΣF = m × ac

As such, one can substitute in the equation for centripetal acceleration (Rule 45) to get the additionally-useful following equation:

ΣF = (m × Vt²) / r

There are several important rules for comprehending centripetal force:

1) Centripetal Force is not a New Force. Most other forces, such as the force of gravity, tension, friction, and the normal force (Subsections V.II - V.IV), are 'independently-defined' forces, meaning they are not dependent on anything else and exist despite of what humans think is possible or impossible. Centripetal force, on the other hand, is composed out of these bedrock forces, whether by a mixture of them or just one. This is because it is the NET force in the inward direction, the net of all the forces acting in the inward direction.

2) Centripetal Force is never in a Free Body Diagram. Because centripetal force is not a new force, it never appears in a free body diagram. In order to determine the centripetal force, you need to draw out your free body diagram and then sum the forces in the inward direction.

3) In is positive, and out is negative. When you sum the forces in the inward direction, the in direction is positive, while the out direction is negative. This is almost the same for what was done before for summing forces, just now you sum them in relation to the in direction, and set them equal to centripetal acceleration instead of m × a. NEVER attempt to sum forces in the "tangential" direction - there is no such thing (you may be thinking of summing in the y or x directions). Instead, sum your torques (see Rule 124).

ΣF = m × ac

As such, one can substitute in the equation for centripetal acceleration (Rule 45) to get the additionally-useful following equation:

ΣF = (m × Vt²) / r

There are several important rules for comprehending centripetal force:

1) Centripetal Force is not a New Force. Most other forces, such as the force of gravity, tension, friction, and the normal force (Subsections V.II - V.IV), are 'independently-defined' forces, meaning they are not dependent on anything else and exist despite of what humans think is possible or impossible. Centripetal force, on the other hand, is composed out of these bedrock forces, whether by a mixture of them or just one. This is because it is the NET force in the inward direction, the net of all the forces acting in the inward direction.

2) Centripetal Force is never in a Free Body Diagram. Because centripetal force is not a new force, it never appears in a free body diagram. In order to determine the centripetal force, you need to draw out your free body diagram and then sum the forces in the inward direction.

3) In is positive, and out is negative. When you sum the forces in the inward direction, the in direction is positive, while the out direction is negative. This is almost the same for what was done before for summing forces, just now you sum them in relation to the in direction, and set them equal to centripetal acceleration instead of m × a. NEVER attempt to sum forces in the "tangential" direction - there is no such thing (you may be thinking of summing in the y or x directions). Instead, sum your torques (see Rule 124).

#

P. Rule .

Time Constant:

The time constant, τ, is a means of determining the time it takes for an exponential equation to get to a percent of its maximum value, calculated similarly to a half-life. The first time constant is 63.2%, which is a universal constant that must be remembered. It is the result of 1 - (1 / e), exactly. This number comes up with some frequency in physics.

Thus, since the first time constant is 63.2% of the time it takes to reach terminal velocity, then 2τ will be the 86.5%, because it increased by 63.2% of the percent remaining until 100%. 3τ will be 95%, and so on and so on. Every increase in the time constant will make the velocity 63.2% closer to terminal velocity. Thus, it will take 6.91τ for the velocity to be 99.9% of the terminal velocity.

Objects that encounter more air resistance and meet their terminal velocity faster, like coffee filters, will have a small time constant, while an object like a baseball will have a larger time constant.

The time constant, τ, is a means of determining the time it takes for an exponential equation to get to a percent of its maximum value, calculated similarly to a half-life. The first time constant is 63.2%, which is a universal constant that must be remembered. It is the result of 1 - (1 / e), exactly. This number comes up with some frequency in physics.

Thus, since the first time constant is 63.2% of the time it takes to reach terminal velocity, then 2τ will be the 86.5%, because it increased by 63.2% of the percent remaining until 100%. 3τ will be 95%, and so on and so on. Every increase in the time constant will make the velocity 63.2% closer to terminal velocity. Thus, it will take 6.91τ for the velocity to be 99.9% of the terminal velocity.

Objects that encounter more air resistance and meet their terminal velocity faster, like coffee filters, will have a small time constant, while an object like a baseball will have a larger time constant.

#

P. Rule .

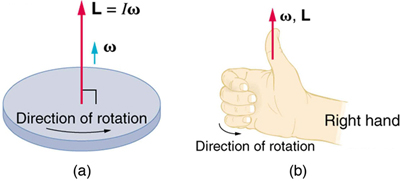

Rotational Right-Hand-Rule:

There is a second right-hand rule, one separate from the Vector right hand rule described in the "Multiplying Vectors" part of Subsection III.II. The 2nd R.H.R. is the Rotational Right-Hand-Rule (R.R.H.R.), which is performed somewhat differently. This rule gives you the direction of the Angular Velocity (ω) and the Angular Displacement (∆θ) of an object in centripetal motion, which are always the same and perpendicular to the plane of the object:

1. First, you need to know the direction of the revolution of the circle itself. This means whether the circle is moving clockwise or counter-clockwise. See Rule 52 for explanation as to how other characteristics of the circle, such as how its placement in 3-dimensional space, will affect the result.

2. Now that you have taken note of the movement of the circle, curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the movement of the circle.

To curl your hand "in the direction of the movement of the circle" means that the curve of your fingers, from the base to the fingertips, matches the movement of the circle: following the path of the your fingers, towards the fingertips, will be identical to the path of the movement of the circle.

Have no restraint in turning your hand to have the path follow correctly - this can be necessary to obtain the correct direction in Step 3.

3. Once your fingers have been curled correctly, stick out your thumb. Your thumb will be pointing in the direction of the Angular Velocity and Angular Displacement of the centripetal motion.

If you have performed this rule correctly, from your point of view (like the bird's eye view of a flat circle in centripetal motion), a circle moving clockwise will always produce a direction in the negative z-axis direction when using the R.R.H.R., and that using it on a circle moving counter-clockwise will result in the positive z-axis direction.

You may wonder, "Why bother with the R.R.H.R. anyways? Can't you just memorize the direction based on whether the circle is moving clockwise or counter-clockwise?". The issue with doing so is that "clockwise" and "counter-clockwise" are observer-dependent directions, and that they can change from whichever perspective you are looking at the circle from (and a problem can require you to look at it from several). Thus, by using the R.R.H.R., you can easily determine which direction the angular velocity & displacement are in by finding the "angular" direction, which, though it can change in positioning depending on perspective, will always be in the same direction.

For example, if you were to determine on the front side of an object in centripetal motion that its direction is outward, and then when you move to the backside that its direction is inward, you would have found the same direction, just from different perspectives. For all intents and purposes, it remains wise to define one view of the object in centripetal motion as being the "front" view, so that any direction inward can be labeled as being on the negative z-axis and any direction outward as being on the positive z-axis.

There is a second right-hand rule, one separate from the Vector right hand rule described in the "Multiplying Vectors" part of Subsection III.II. The 2nd R.H.R. is the Rotational Right-Hand-Rule (R.R.H.R.), which is performed somewhat differently. This rule gives you the direction of the Angular Velocity (ω) and the Angular Displacement (∆θ) of an object in centripetal motion, which are always the same and perpendicular to the plane of the object:

1. First, you need to know the direction of the revolution of the circle itself. This means whether the circle is moving clockwise or counter-clockwise. See Rule 52 for explanation as to how other characteristics of the circle, such as how its placement in 3-dimensional space, will affect the result.

2. Now that you have taken note of the movement of the circle, curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the movement of the circle.

To curl your hand "in the direction of the movement of the circle" means that the curve of your fingers, from the base to the fingertips, matches the movement of the circle: following the path of the your fingers, towards the fingertips, will be identical to the path of the movement of the circle.

Have no restraint in turning your hand to have the path follow correctly - this can be necessary to obtain the correct direction in Step 3.

3. Once your fingers have been curled correctly, stick out your thumb. Your thumb will be pointing in the direction of the Angular Velocity and Angular Displacement of the centripetal motion.

If you have performed this rule correctly, from your point of view (like the bird's eye view of a flat circle in centripetal motion), a circle moving clockwise will always produce a direction in the negative z-axis direction when using the R.R.H.R., and that using it on a circle moving counter-clockwise will result in the positive z-axis direction.

You may wonder, "Why bother with the R.R.H.R. anyways? Can't you just memorize the direction based on whether the circle is moving clockwise or counter-clockwise?". The issue with doing so is that "clockwise" and "counter-clockwise" are observer-dependent directions, and that they can change from whichever perspective you are looking at the circle from (and a problem can require you to look at it from several). Thus, by using the R.R.H.R., you can easily determine which direction the angular velocity & displacement are in by finding the "angular" direction, which, though it can change in positioning depending on perspective, will always be in the same direction.

For example, if you were to determine on the front side of an object in centripetal motion that its direction is outward, and then when you move to the backside that its direction is inward, you would have found the same direction, just from different perspectives. For all intents and purposes, it remains wise to define one view of the object in centripetal motion as being the "front" view, so that any direction inward can be labeled as being on the negative z-axis and any direction outward as being on the positive z-axis.

#

P. Rule .

To determine the angular velocity of an object in centripetal motion when looking at it from the side, as depicted in figure (a) below, you would need to perform the exact same steps of the Rotational Right-Hand-Rule (see Rule 51): curl your fingers in the direction of the movement of the circle, with the added cognizance of the positioning your hand. You must make sure to turn your hand to best reflect the motion of the object, as if the path of your fingers was on the same plane as the object, as seen in figure (b).

An example of how the R.R.H.R. would be carried out with respect to an object in centripetal motion as viewed from the side, in this case producing the positive y-direction. Courtesy of Libretexts.

This enables for directions to be found in the negative and positive x and y directions.

An example of how the R.R.H.R. would be carried out with respect to an object in centripetal motion as viewed from the side, in this case producing the positive y-direction. Courtesy of Libretexts.

This enables for directions to be found in the negative and positive x and y directions.

# Conical Pendulum: A pendulum (a hung weight that can swing freely back and forth in oscillations) that swings circularly, the motion of which forms a conical shape. In these problems, the centripetal motion will be along the horizontal plane (if hanging normally), or whichever plane the problem specifies if moving against gravity.

# Uniform Circular Motion: Centripetal motion at a constant angular velocity. This motion thus has no change in angular velocity, no angular acceleration, nor any tangential acceleration. An object spinning on the y-plane, like a yo-yo, is considered to be in nonuniform circular motion, as the force of tension will always be changing as it moves through the air (weakest when at its maximum height, and strongest at the bottom), in order for the net centripetal acceleration to be conserved. The yo-yo will take longer to move through the top semicircle of the revolution than the bottom, since the tangential speed is greater at the bottom. For a conceptual refresher, watch this video proof.

#

P. Rule .

The acceleration of any object in non-uniform circular motion has two perpendicular components: tangential acceleration and centripetal acceleration. Thus, to determine the absolute magnitude of the acceleration of an object in centripetal motion at any moment, you would simply perform the Pythagorean Theorem with the two component accelerations being a and b.